Tonya Butler lives 24 miles east of downtown Atlanta in the small city of Conyers, Georgia. Until recently, Butler, 53, worked in Atlanta as a childcare worker for a broadcasting company, a job that required an hour-and-a-half commute.

“It was really ridiculous,” she says. “It was the traffic, it was the influx of people moving to Georgia. It affected my quality of life tremendously, so much so that I had to leave a job in the city and take a massive cut in pay.”

Butler was born and raised in Atlanta, one of the most racially and economically segregated cities in the country. She has witnessed public housing torn down and replaced by flashy, unaffordable condos, and she’s seen taxes follow population increases. Meanwhile, her income has remained stagnant. And in the past decade, Atlanta’s median home sale price has risen over 50%, from about $196,000 to $296,000 – out of reach for people like Butler.

Regional Atlanta is one of the ten largest metropolitan areas in the US, and it ranks 316th in terms of density. It was designed to be a low-density city – and that doesn’t correlate well to its population growth. It was the fourth-fastest-growing metro area in the country over the past decade, and according to the National Association of Realtors, it’s poised to become one of the top ten US housing markets post-Covid. Though Atlanta has a population of just over 500,000, it’s estimated to grow to 1.2 million in the next few decades.

Low housing density and racial segregation go hand in hand in Atlanta, the former creating a housing crisis that will only worsen as the city grows and the market cannibalises affordable housing. That’s why the city has recently published the Atlanta City Design Housing (ACDH) initiative, a project that deep-dives into the metropolis’s history of restrictive and exclusionary zoning laws. Its aim is to better understand how the city’s built environment became what it is today and how it might remedy the situation to create more naturally occurring affordable housing.

Zoning out affordability

“We zoned out more naturally affordable housing options over the course of 100 years because we wanted to do intentional economic and racial exclusion in neighbourhoods,” explains Joshua Humphries, director of housing and community development for the city of Atlanta. “We built the city this way on purpose, and now that built environment is running up against a significant population growth that we haven’t seen in 50 years.”

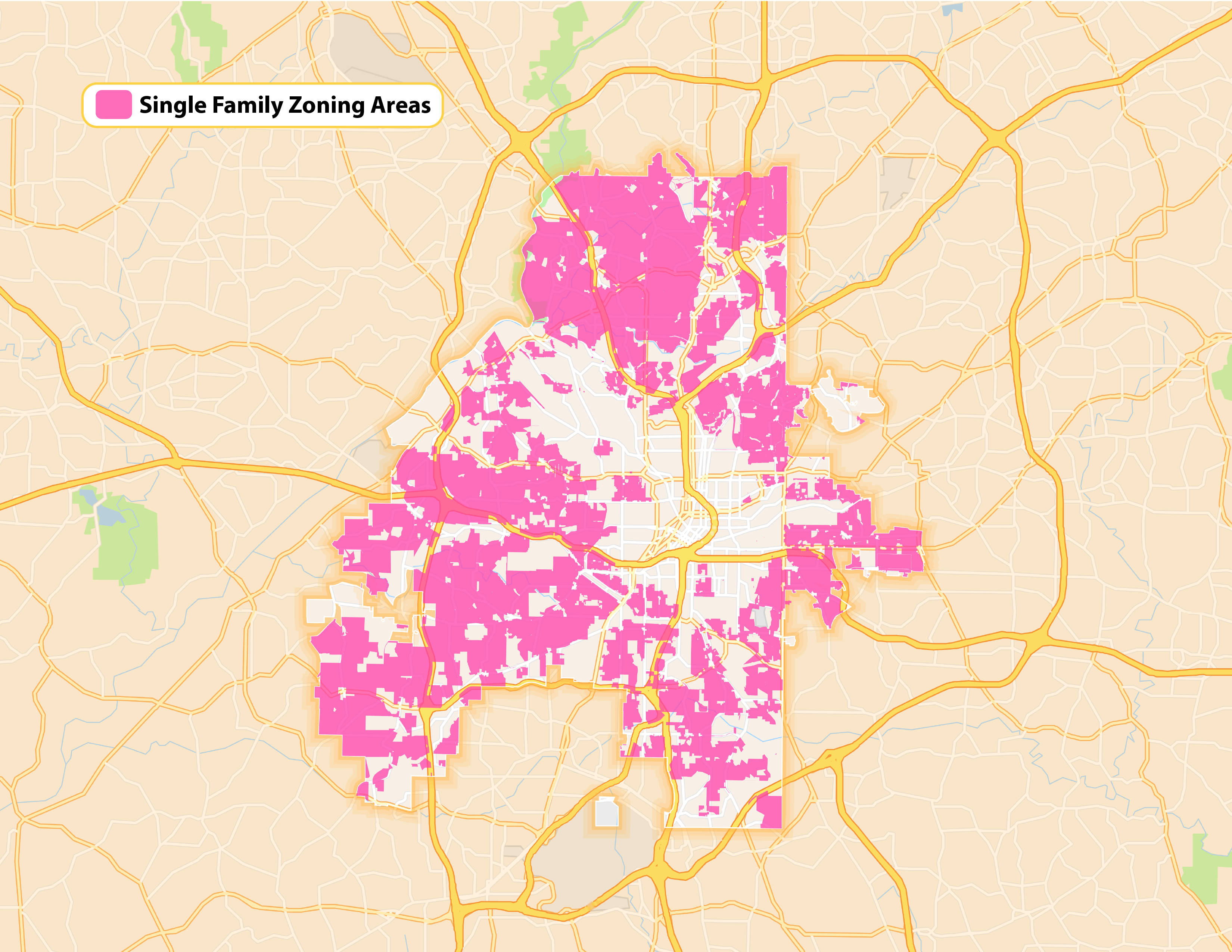

In 1940, Atlanta was more than twice as dense as it is today, but a century of racist zoning laws and redlining severely limited the types of homes that could be built in large swaths of the city. By 1982, 60% of the city had been zoned exclusively for single-family housing, a not-so-subtle way of segregating lower socio-economic classes, which were predominantly African American, out of the most desirable parts of the city. As a result of this strict zoning code, housing types like duplexes, basement apartments and apartment buildings are rare in the city today.

Nearly half of Atlanta renters are rent burdened, according to the most recent census data, and that’s not limited to low-income renters. Middle-income earners are also increasingly unable to afford their dwellings, so many of the solutions proposed in ACDH target creating moderately priced units, as well. The project implements elements of Atlanta Mayor Keisha Lance Bottoms’ 2017 Housing Affordability Action Plan, which set a goal of creating 20,000 affordable-housing units by 2026. To achieve this, a bundle of legislation that effectively aims to end single-family zoning will soon make its way to Atlanta City Council, following the example of other cities like Minneapolis and Seattle in doing so. Notably, this project doesn’t highlight plans to create affordable housing through government subsidies.

“We’re acknowledging the importance of naturally occurring affordable housing in the city,” says Tim Keane, commissioner of city planning. “We can’t subsidise our way out of this problem. So how do we grow in a way that, just by the very nature of the building types and the density we’re achieving, we can be a more affordable city?”

Planning a more equitable city

The ACDH project breaks down the city into “growth areas” and “conservation areas” based on the physical nature of Atlanta. Growth areas represent the city’s densest locales that are ripe for further urban development. Conservation areas make up a larger portion of the city and include low-density residential regions and green space. To maintain the form and character of these neighbourhoods, “subtle” density could be added, which looks very different from building apartment buildings or other multifamily dwellings.

One creative solution to achieve subtle density is to legalise additional living spaces on single-family properties, such as basement apartments or accessory dwelling units (ADUs) – apartments that by their less desirable nature make them more affordable. These additions would also give homeowners another source of income through rent.

“If just 15% of the single-family properties in the city right now were to add a second unit, that would achieve 11,500 units,” says Keane.

Another big piece of zoning reform legislation would eliminate parking minimums, which mandate how many spots a property is required to have. These requirements are a relic of Atlanta’s exclusionary, suburban-style zoning that relies heavily on cars. Parking minimums also disincentivise homeowners to rely on public transit to get around, which only exacerbates Atlanta’s traffic problems. Other major cities, including San Francisco, Honolulu and Chicago, have recently eliminated parking minimums as well.

Atlanta’s Department of City Planning has already proposed an expansion of the Urban Enterprise Zone (UEZ) programme, which is working its way to the Georgia General Assembly for a vote. The UEZ was created in the 1980s to spur redevelopment in the city. It currently requires that at least 20% of total housing units created be dedicated to affordable housing for a ten-year property tax abatement.

In its present form, explains Humphries, the policy “only allows this tax subsidy to be used in low-income areas of the city, so it reinforces the segregation through economic exclusion and ensures that low-income residents are concentrated with low-income residents and that there aren’t affordable-housing options in higher-cost areas.”

The biggest challenge we face [against changing zoning laws] is the resistance to change. Tim Keane, commissioner of city planning

The city is proposing that the tool be used citywide, particularly in high-access, high-amenity areas rather than only in low-income ones.

“The biggest challenge we face [against changing zoning laws] is the resistance to change,” says Keane. “As much as they might acknowledge the discriminatory practices that got us where we are, people just tend to be comfortable with the way things are. In my experience, people are quick to support inclusionary zoning and requiring developers to build affordable housing, but when you start saying, ‘What about your neighbourhood and your block? Is there something we can do there?’ People have a hard time supporting that.”

Buckhead is a high-income Atlanta suburb that falls under the conservation area bucket. An article discussing the proposed rezonings in a local Buckhead publication questions the negative impact of some neighbourhoods being “exclusive”.

“I will assume that Mayor Bottoms, Tim Keane and Atlanta City Design all have the best intentions,” wrote real estate agent Ben Hirsh. “They want to increase the supply of housing to keep pace with the increasing population and help pull people out of poverty who have been disadvantaged. I think that is a great premise, but they should work to find a way to do it without driving out those with more wealth. If you take away the housing choices that a wealthy individual is looking for, then they will go elsewhere to find it and take their tax money with them. That does not contribute to a healthy and diverse city.”

For Humphries, making Atlanta a healthier and more diverse city comes down to two questions. “There’s the math question, the economics of a growing city and restrictive land use, and how the map works to have affordability long term,” he says. “But there’s also this moral question about the city we want to become. [That means] reckoning with our history, the structural discrimination in our zoning code, the ways in which we designed the city to be exclusionary and the ways in which we design the city to be more inclusive than they are today.”