It’s been ten months since Covid-19 swept across the US, and the small municipality of Yeadon, Pennsylvania, still has not received any direct assistance from the federal government.

That’s not to say that the trillions of dollars in stimulus from Congress haven’t buoyed the fortunes of this majority-Black borough near Philadelphia. Supercharged unemployment benefits and $1,800 in cash to eligible households helped keep residents going. Yeadon benefits from aid to regional transit and education agencies, too.

But the $150bn in Covid-related assistance that was allocated to cities and states in March went only to municipalities of 500,000 or more residents. Yeadon was far too small to benefit, and it isn’t alone. By the National League of Cities’ estimate, 29% of US municipalities did not receive any funds from the CARES Act.

“[We need aid so] that cities or municipalities can keep functioning,” says Rohan Hepkins, the longtime mayor of Yeadon. “We have a lot of people who have lost jobs, which affects their mortgage payments and taxes. We plan to experience a downturn in the collection of taxes due to the pandemic.”

Still awaiting details of Biden’s stimulus plan

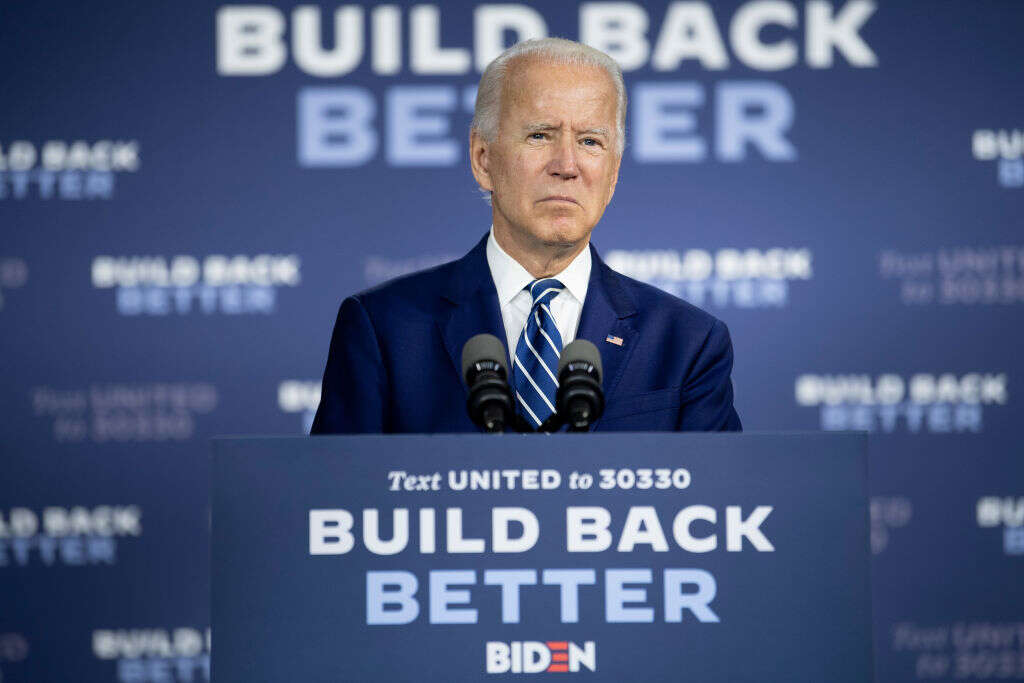

Throughout 2020, Senate Majority Leader Mitch McConnell refused to include aid to states and localities in federal stimulus efforts, arguing that it would help governments he characterised as being poorly run before the pandemic. Now that Democrats have won control of the Senate, however, the Republican Party will no longer be able to set the agenda. In a proposal released Thursday evening, president-elect Joe Biden included $350bn for state, local and tribal governments.

“Providing unrestricted relief to state and local governments… is always a tough sell in Washington.” Tracy Gordon, Urban-Brookings Tax Policy Center

Biden’s exact plans are not yet clear. His spokespeople did not reply to questions about post-inauguration stimulus plans, and Democratic congressional representatives report being similarly unenlightened. (There are, after all, a lot of other things going on.) A few hints have dropped, however, that local leaders like Hepkins and his counterparts in larger cities should not get too excited for direct aid to bolster their flagging revenues.

This month the Washington Post reported that local assistance in a new stimulus package might be tailored to specific needs (like education and childcare) rather than revenue replacement. It’s unclear precisely what that means, but it sounds like there could be extremely tight guidelines on how money distributed to these authorities can be spent.

“Providing unrestricted relief to state and local governments – funds that mayors and governors can direct to their own purposes – is always a tough sell in Washington,” says Tracy Gordon, senior fellow with the Urban-Brookings Tax Policy Center. “What I’ve heard so far is that money would be directed to schools, transit and other specific functional areas. That helps places in terms of freeing up resources that they can then divert to their own purposes. But in terms of economic benefit, it falls somewhere between unrestricted aid to state and local governments and aid to small businesses.”

Gordon says the impetus to provide direct support may be lessened because the fiscal fallout for states and cities hasn’t been on the apocalyptic level many observers initially predicted in the spring of 2020. Massive federal expenditures so far have cushioned the blow, helping to maintain consumer spending and sales tax revenues. Unemployment and hardship have been concentrated among lower-income Americans, so jurisdictions with more progressive tax regimens also aren’t suffering as badly as had been feared. The Urban Institute reports that a handful of states, including Vermont and Utah, even reported surprisingly strong growth with over 3% increases in year-over-year tax revenues in 2020. California enjoyed a surplus of $15bn at year’s end.

Cities and states should expect long-term economic pain

Many parts of the country are not so lucky, however. The Urban Institute found that 28 states saw total revenue declines between March and November 2020, with the country overall seeing a fall of 3.2%. Where possible, they’ve used short-term borrowing, issued tax anticipation notes and employed various accounting gimmicks to paper over the losses. But these measures won’t last forever.

“Once all those things are due, states start to really think about: how much are we going to actually have to cut?” says Chris Goodman, assistant professor of public administration at Northern Illinois University. “Because all those short-term fixes are gone at that point.”

Cities are in an even worse position, as cash-strapped states may decide to cut funding for localities just when they need it most. US cities often rely heavily on property tax revenues, and it can take years for the full fiscal impact on these revenues to be fully felt. The National League of Cities found that in the past three recessions – of 1991, 2001 and 2007 – the low points for city revenues and expenditures lagged the beginning of the downturn by two years.

In the meantime, the additional costs brought on by the pandemic, ranging from protective equipment and cleaning to overtime associated with protests, continue piling up.

“We’ve had to take a lot more precautions, we’ve had to buy more PPE, we’ve had to enact more overtime during the civil unrest, during the elections and things like that,” Hepkins says.

In the short term, as vaccinations slowly roll out and infection rates rise, the situation is likely to get worse before it gets better. Cities and states never recovered to pre-pandemic employment levels, and after the beginnings of a recovery in the middle of the year, job losses began accelerating again in late 2020. There are 1.3 million fewer public-sector jobs today than in February 2020, with an additional 45,000 losses in December. Employment has been reduced to levels last seen in 2001, when the population and economy were smaller (and, of course, there wasn’t a deadly respiratory infection stalking the land).

Goodman works with a lot of small cities and suburban jurisdictions in the Chicago area, and he says city managers and mayors are drawing up fresh lists of potential layoffs. The fastest way to get money into their bank accounts, he argues, is with direct aid.

“All of the issues associated with needs-based aid for people also applies to local governments: the more rules and eligibility requirements, the longer this takes,” says Goodman. “If we had all the time and information in the world, we would target this very specifically, and it would be very precise. But we don’t have great data, and we don’t have a lot of time. Better to get it out and deal with it on the back end.”

A September report from the Congressional Budget Office showed that of all the CARES Act’s relief efforts, including the supercharged unemployment assistance and direct payments, the most substantial cumulative effect on national gross domestic product came from aid to state and local government. Payments to individuals could be saved, while funds sent to lower levels of government were immediately spent.

The calculus of the Biden administration will be shaped not just by the policy merits but by the politics of the new stimulus package. With the barest of margins in the Senate, Democrats will need Republican support to overcome the arcane rules of the filibuster (which requires 60 votes to secure passage). The only way around that is through a process known as budget reconciliation, which can be used only once per fiscal year.

But Biden has indicated that he wants to pass the new Covid relief package with Republican support. That means his team may need to make concessions to conservative rhetorical framing of the issue, like McConnell’s, which could lower that $350b topline number and kill the idea of direct aid.

For Hepkins, that doesn’t make a lot of sense. Any help is welcome, of course, but he says local leaders know the needs of their communities best, and they know where the money needs to be spent.

“The federal government shouldn’t dictate where we spend it,” says Hepkins. “They just don’t know how the pandemic affects different municipalities differently. So I’d like to see more flexible aid to cities and municipalities.”