Ken Livingstone hoped the charge would reduce congestion, radically improve bus services, make journey times more consistent for drivers and make increase efficiency for those distributing goods and services throughout the city.

Key measures show it has been a success: in 2006, Transport for London (TfL) reported that the charge reduced traffic by 15 per cent and congestion – that is, the extra time a trip would take because of traffic – by 30 per cent. This effect has continued to today. Traffic volumes in the charging zone are now nearly a quarter lower than a decade ago, allowing central London road space to be given over to cyclists and pedestrians.

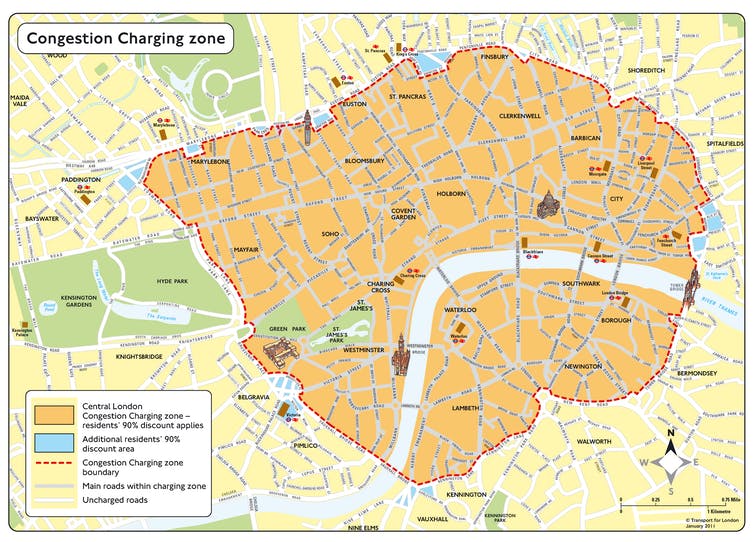

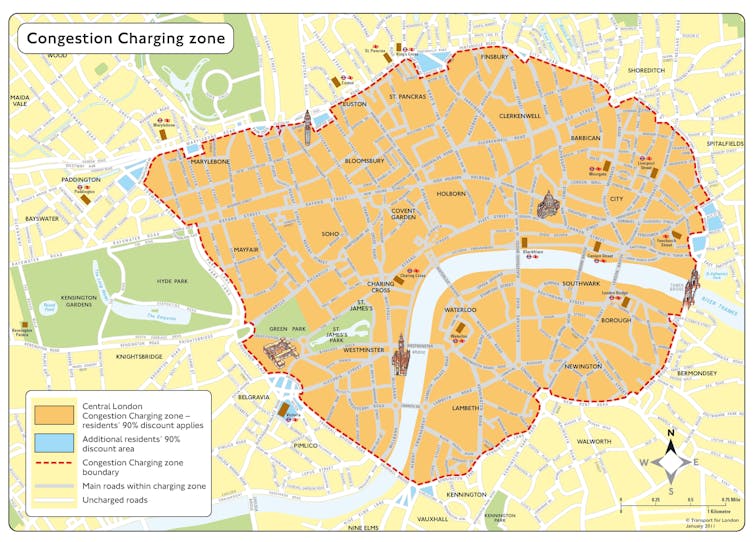

Congestion charging zone in Central London. Image: Transport for London.

The charge covers a 21km² area in London. It’s a simple system: if you enter the zone between 7am and 6pm on a weekday, you pay a flat daily rate. The charge has risen gradually from £5 in 2003 to £11.50 today. Residents receive a 90 per cent discount and registered disabled people can travel for free. Emergency services, motorcycles, taxis and minicabs are exempt.

Recipe for success

Today, city leaders in places such as New York are facing resistance, as they consider introducing their own congestion charge in the urban core. But the same thing happened in London, 15 years ago: notable push-back came from Westminster Council, which took the issue to court, claiming it would cut residents off from education and healthcare services, but lost. If it weren’t for the 1999 law which centralised certain powers to the mayor, the charge may not have been realised at all.

London’s congestion charge succeeded for two key reasons: it had a clear and convincing premise, and it was just one part of larger efforts to improve travel across all forms of transport in the city. The case for congestion charging was simple: the charge would reduce traffic in the city centre and generate funds to reinvest in improving public transport services.

On the day the congestion charge was introduced in London, 300 extra buses were added to the Central London bus network to give people an alternative to driving and avert the anticipated mayhem. One year later, Livingstone reported that 29,000 more passengers had entered the charging zone by bus during the morning rush hour, compared to a year before. Between 2002 and 2014, the number of private cars coming into the zone fell by 39 per cent.

Getting busy

But while car numbers are down, the number of private for hire vehicles – your minicabs and Ubers – is up. Trips by taxi and private for hire vehicle as the main mode of the journey increased by 9.8 per cent between 2015 and 2016 alone – and 29.2 per cent since 2000. Today, more than 18,000 different private hire vehicles enter the congestion charging zone each day, with peaks on Friday and Saturday nights.

This has reduced the speed of traffic through the city centre, which in turn has affected the bus network. City Hall investigated and concluded that traffic congestion was the primary reason why bus usage was down in London: the slower the speed along bus routes, the greater the fall in passenger numbers.

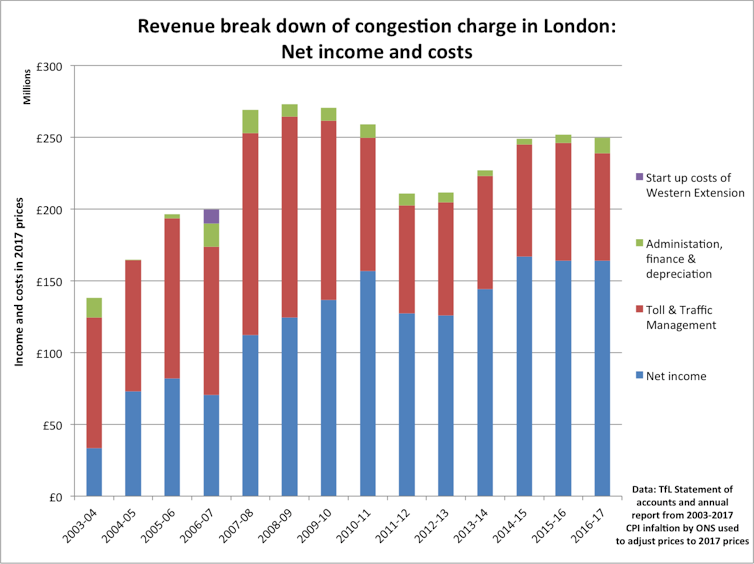

Breakdown of revenue collected each year from the congestion charge, and the net income after costs accounted for. Image: author created from Transport for London Statements of Accounts and Annual reports for years 2003 to 2017.

Taxis and minicabs are exempt from paying the congestion charge, presenting a further, financial challenge for TfL. While minicab registrations have soared from 49,854 in 2013 to 87,409 in 2017, the income from the congestion charge has flat-lined. Last year, TfL registered its first drop in congestion charge income since 2010.

Stockholm solution

Now, authorities are looking abroad for solutions. Inspired by cities such as Stockholm, the London Assembly (the city’s government scrutiny body) has recommended extending the congestion charging zone and replacing the daily flat rate with a charging structure which would reflect when and where drivers enter the zone and how much time they spend there. In Stockholm, the zone covers 35km², capturing two-thirds of the city’s residents in a scheme with varying charge levels depending on the time of the day – the maximum daily charge does not exceed 105 Swedish Krona (about £9.20).

The London Assembly also recommended devolving the national vehicle exercise duty (an annual charge for private vehicle ownership, based how polluting the vehicle is) to the Mayor of London’s office. This would give city leaders another means to encourage sustainable travel.

In his 2018 Transport Strategy, Sadiq Khan – London’s current mayor – aims to have four out of every five trips through the city made by public transport, cycling or walking by 2040 – up from two-thirds today. The congestion charge will be kept under review, but the strategy hints that it could be merged with the city’s Low Emission and Ultra Low Emission Zones (the latter is set to start in 2019), which offer cheaper rates for low-emission vehicles, to help tackle air pollution.

Khan and TfL have a huge budget hole to fill, having lost their £700m a year operational grant from national government. Khan’s manifesto pledge to freeze fares will cost £640m over his term, and at the same time passenger numbers and fare revenues are down £240m. A reformed congestion charge could not only ease traffic – it could provide a much-needed new revenue stream for TfL. The mayor also seems to be investigating ending the exemption for minicabs.

![]() After 15 years of operation, London’s congestion charge can be celebrated as a success. It has set the bar for other cities – demonstrating that road pricing can only be successful as part of strategy that offers efficient, sustainable alternatives for car drivers. Looking ahead, the congestion charge needs reform to meet the financial and logistical challenge of providing a good transport system for Londoners.

After 15 years of operation, London’s congestion charge can be celebrated as a success. It has set the bar for other cities – demonstrating that road pricing can only be successful as part of strategy that offers efficient, sustainable alternatives for car drivers. Looking ahead, the congestion charge needs reform to meet the financial and logistical challenge of providing a good transport system for Londoners.

This article was originally published on The Conversation. Read the original article.