As our cities grew during the industrial revolutions many, such as Glasgow, built extensive tramways as an industrial means of transport. They then went through a metro-midlife-crisis, seduced by the apparent freedom offered by the motor car. We did not get that freedom: instead, we found sprawl moving us further apart, negating any mobility gains for those who could afford their car while creating barriers through our cities to everyone else.

As our cities emerge into another stage in life, so too are we re-examining how we support people to travel through and within them. Manchester, Edinburgh, and Nottingham have cracked on with rebuilding tramways. Glasgow is catching up having established a Connectivity Commission “to generate bold, fresh ideas to transform Scotland’s biggest city; making it a more liveable and breathable place”.

Among these bold fresh ideas is the re-introduction of trams to Glasgow, once the home of one of Europe’s largest and busiest tram networks. But how did Glasgow go from a tram-city to a motorway-city? And how could the city move forward to support inclusive transport for the people?

Reimagining trams in Glasgow

The only remaining light rapid transit in the city is the Glasgow Subway, the third-oldest underground system in the world, which forms a 10.5km circular route. But two decades prior to beginning construction of the subway, the UK Parliament passed the Tramways Act of 1870, which set out to “facilitate the construction and regulate the working of tramways”. It allowed district councils to construct tram lines under the clause that private companies be given the operating lease for a minimum of 21 years.

In 1872, Glasgow Town Council (later Glasgow Corporation, now Glasgow City Council) laid a 4km route from St. George’ Cross, north of the River Clyde, along the Jamaica Bridge to Eglinton Toll on the south side. The tram lines had an unconventional track gauge of 1,416mm compared with the standard gauge of 1,435mm. At the time, Glasgow was a centre for shipbuilding: the unusual gauge allowed for heavy rail wagons to run on short sections of the tram lines to carry freight to the shipyards.

The council handed working responsibility of the tramway to the newly formed Glasgow Tramway & Omnibus Company (GTOC), which operated horse-drawn wagons. Its tenure expanded in 1893 when it took over the neighbouring Glasgow and Ibrox Tramway and the Vale of Clyde Tramway in Govan.

One year later, Glasgow Town Council withdrew GTOC’s responsibility for the network after their minimum 21-year lease, as per the Transport Act 1870, expired. The tramways were taken into public ownership in the form of Glasgow Corporation Tramways in June 1894.

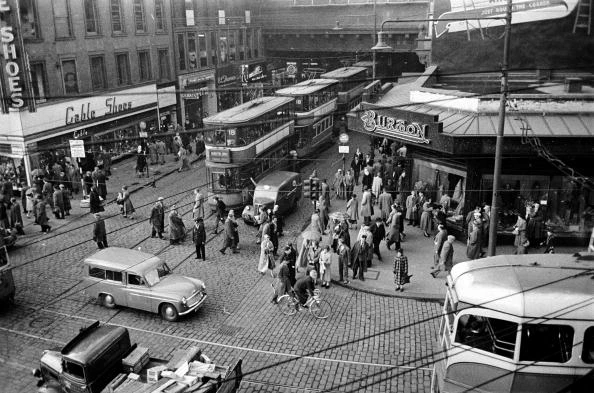

The Corporation oversaw the electrification of the tramways in 1898 and the last horsedrawn tram was retired in 1902. By 1938, Glasgow had one of the largest tram networks in Europe, with more than 1,000 trams operating on a total of 227km of track. The tramways served a vast population of the Clyde Valley with routes running to towns, such as Clydebank and Bishopbriggs, more than 10km outside the city centre.

The frequency of trams on certain routes was regularly one every two to three minutes with some stops in the city centre witnessing trams, of varying routes, every 12.5 seconds. But despite the people’s love for their tramway, the system would eventually reach the end of the line. From 1953, the network was gradually reduced in size and frequency until, in September 1962, more than a quarter of a million Glaswegians took to the streets to watch the last tram car pass through the city.

The demise of the trams was evoked by various factors and parties. From the end of the First World War, private car ownership was increasing across the UK. Buses manufactured for the transport of troops during the war were later sold to private companies who became direct competitors to the tramways. Trams were seen to impede on the freedom of private car owners in the city: the authorities believed that removing the tramways and replacing them with buses would allow for easier transport in and around Glasgow.

People who had previously used the trams were expected to transfer to buses: all the same, the end of the trams fuelled a sharp rise in car ownership during the 1930s and ’40s. “After the Second World War, their fate was sealed and urban planners were obsessed by car-based redevelopment of war-damaged cities, a vision which never included trams on urban motorways or roundabouts,” notes Oliver Green, former curator of the London Transport Museum.

Trams get trolleyed

Trolleybuses, which used the same overhead power lines as the trams but weren’t bound by fixed rails, were the initial successors to the tramways in Glasgow. They operated on the same routes as the previous trams but were considered safer and more convenient for other road users, as they could pull into the side of the road to let passengers alight. The first trolleybuses began in April 1949, but were short-lived: the service was scrapped in 1967, in favour of diesel-powered buses.

One consequence of the tramway closure was a fall in gender equality in the Corporation workforce. During the First World War, women were allowed to become tram drivers for the first time, as well as guards and conductors, and this continued after the war until the tramways closed. But women were considered to lack the necessary strength to steer buses that, at the time, had no power steering.

Glasgow was the last city in the UK to operate an urban tramway until the resurrection of new tram systems at the end of the century, when the Manchester Metrolink opened in 1992. During the 1990s, indeed, there were several attempts to bring tramways back to key strategic routes that lacked access to the heavy rail network in Glasgow, such as the route planned between Maryhill in the north-west of the city to Easterhouse in the far east.

What lessons can the city learn from Edinburgh’s tramway experience? Almost scrapped just weeks before construction started in 2007, the system opened in May 2014, at twice its expected budget, three years behind schedule and on a route less than half of what had been initially proposed. However, ridership has steadily increased.

By 2017, the system achieved pre-tax profitability two years ahead of schedule. In March 2019, Edinburgh Council approved a 4.6km extension to Leith, which opened earlier this year. The success of the Edinburgh tram is not surprising: as in Glasgow, the city’s tenements streets led to sustained high population densities, a key factor leading to high ridership of mass transit.

To meet climate and air pollution targets, Glasgow must adjust street space away from private cars, reducing the utility that driving currently presents. A new tramway could entice current drivers onto public transport. In the past people made the direct jump from trams to cars, missing out buses: perhaps that historical jump in reverse is what’s needed to help Glasgow become the modern, inclusive European city it aspires to be.

This article is by Jack McInally and Bethany Adam, University of Glasgow.

[Read more: Why is light rail still in the sidings? The case for trams]