The world’s biggest cities have larger populations and higher economic outputs than some countries. But as they grow in size and complexity, cities are also facing thorny challenges that threaten the health and happiness of residents. In response, cities must manage their resources and priorities to create sustainable places for visitors and residents, and foster innovation and growth.

Enter Barcelona – the capital of Catalonia, in Spain – where a bold stroke of urban planning first introduced “superblocks” in 2016.

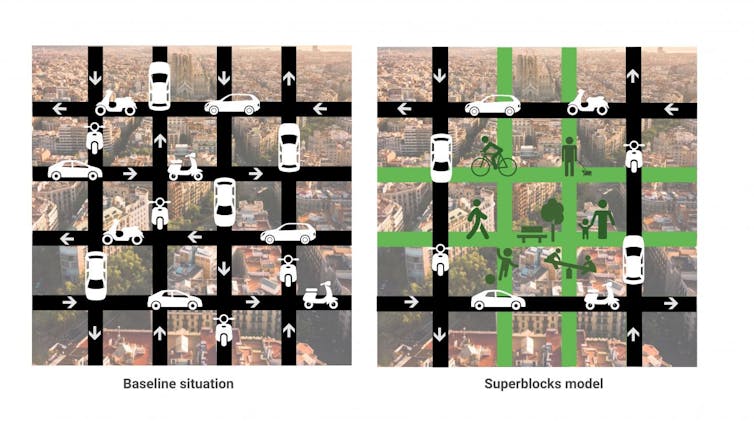

Superblocks are neighbourhoods of nine blocks, where traffic is restricted to major roads around the outside, opening up entire groups of streets to pedestrians and cyclists. The aim is to reduce pollution from vehicles, and give residents much-needed relief from noise pollution. They are designed to create more open space for citizens to meet, talk and do activities.

Health and well-being boost

There are currently only six superblocks in operation, including the first, most prominent one in Eixample. Reports suggest that – despite some early push back – the change has been broadly welcomed by residents, and the long-term benefits could be considerable.

A recent study carried out by the Barcelona Institute for Global Health estimates that if, as planned, 503 potential superblocks are realised across the city, journeys by private vehicle would fall by 230,000 a week, as people switch to public transport, walking or cycling.

The research suggests this would significantly improve air quality and noise levels on the car-free streets: ambient levels of nitrogen dioxide (NO₂) would be reduced by a quarter, bringing levels in line with recommendations from the World Health Organisation (WHO).

The plan is also expected to generate significant health benefits for residents. The study estimates that as many as 667 premature deaths from air pollution, noise and heat could be prevented each year. More green spaces will encourage people to get outdoors and lead a more active lifestyle.

This, in turn, helps to reduce obesity and diabetes and ease pressure on health services. The researchers claim that residents of Barcelona could expect to live an extra 200 days thanks to the cumulative health benefits, if the idea is rolled out across the city.

There are expected to be benefits to mental health, as well as physical health. Having access to such spaces can stave off loneliness and isolation – especially among elderly residents – as communities form stronger bonds and become more resilient.

Stumbling blocks

It was Salvador Rueda, director of the Urban Ecology Agency of Barcelona, who first championed the introduction of superblocks – and he argues that the idea could be used in any city. Even so, authorities looking to expand the concept in Barcelona or beyond will need to be mindful of some concerns.

Changes like these require capital investment. Even as the car-free streets are transformed with urban furniture and greenery, the remaining major roads will likely have to accommodate heavier traffic.

Further investments in local infrastructure – such as improving surrounding roads to deal with more traffic, or installing smart traffic management system – could be required to prevent serious congestion. Then the question remains, how to finance such investments – a higher tax rate is unlikely to be popular.

[Read more: Ban cars: Why cities are embracing the call for car-free streets]

What’s more, whenever a location becomes more desirable, it leads to an increase in property demand. Higher prices and rent could create pockets of unaffordable neighbourhoods. This may lead to use of properties for investment purposes and possibly, displacement of local residents.

It’s also worth noting that Barcelona is an old and relatively well-planned European city. Different challenges exist in emerging global cities across Asia, Africa and Latin America – and in younger cities in the US and Australia. There is a great deal of variation in scale, population density, urban shape and form, development patterns and institutional frameworks across the cities. Several large cities in the developing world are heavily congested with uncontrolled, unregulated developments and weak regulatory frameworks.

Replicating what’s been done in Barcelona may prove difficult in such places, and will require much greater transformations. But it’s true that the basic principles of superblocks – that value pedestrians, cyclists and high-quality public spaces over motor vehicles – can be applied in any city, with some adjustments.

Leading the way

Over the history of human civilisation, great cities have been at the forefront of innovation and social progress. But cities need a robust structure of governance, which is transparent and accountable, to ensure a fair and efficient use of resources. Imposing innovation from the top down, without consultations and buy-in, can go squarely against the idea of free market capitalism, which has been a predominant force for modern economies and can lead push-back from citizens and local businesses.

Citizens must also be willing to change their perspectives and behaviour, to make such initiatives work. This means that “solutions” to urban living like superblocks need to have buy-in from citizens, through continuous engagement with local government officials.

Successful urban planning also needs strong leadership with a clear and consistent vision of the future, and a roadmap of how that vision can be delivered. The vision should be co-developed with the citizens and all other stakeholders such as local businesses, private and public organisations. This can ensure that everybody shares ownership and takes responsibility for the success of local initiatives.

There is little doubt that the principles and objectives of superblocks are sound. The idea has the potential to catch on around the world – though it will likely take a unique and specific form in every city.

Anupam Nanda, Professor of Urban Economics and Real Estate, University of Reading.

This article is republished from The Conversation. Read the original article.