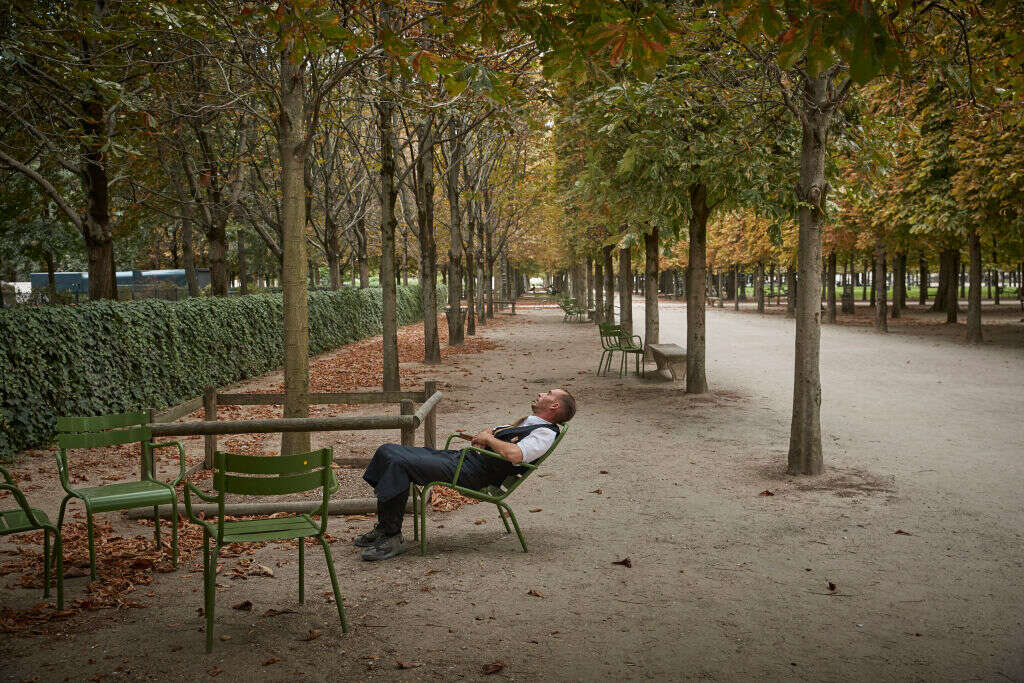

Paris has long been a place where it’s easier to take a scenic stroll than walk barefoot across a lawn. The City of Lights is not a city of parks: with just 9.5% of its land given over to gardens and public green spaces, it falls shockingly short of peer cities such as London (33%) or Madrid (35%). But in its bid to become more resilient in the face of climate change and rising temperatures, Paris is now embracing nature in rapid fashion.

“In the past, we’ve sometimes protected ourselves from nature as if it meant us harm,” Paris Mayor Anne Hidalgo told CityLab in 2018. “We’ve rediscovered quite simple things, and it gives me pleasure, along with my team, to return to simplicity.”

A socialist who won re-election in 2020 preaching an anti-car, pro-density campaign of civic transformation, Hidalgo envisions the French capital becoming a “15-minute city,” where everything one needs is within a quick walk or bike ride. It’s the animating philosophy of much of the city’s recent spate of environmental policies. Nestled within that larger shift is an awareness of rising temperatures and a need to create more accessible, heat-dispersing, shade-providing parks and green spaces in a city that may be picturesque but not protected: last year’s record heatwaves topped 42°C (108°F) in Paris, and in 2017, a school courtyard on the city’s outskirts became so hot (55°C) that one could fry an egg on the pavement.

To understand the plan Paris is undertaking to mitigate heat risks, it’s important to understand Paris beyond its traditional definitions and boundaries. The Greater Paris region, known as the Île-de-France, includes immigrant-heavy rings of suburbs known as banlieues, such as Seine-Saint Denis, which have a dearth of parks and public spaces (they also provide the bulk of the region’s essential workers and were the site of police brutality protests this summer). Planning for these regions is governed by the Métropole du Grand Paris, a larger regional council made up of 131 communes, including Paris. Banlieue residents aren’t the Parisians who famously leave for the coast or countryside during the peak heat of August.

“It’s partially a question of vegetation,” says Jean Jouzel, an acclaimed French climatologist. “You may be able to cool off in movie theatres or shops, but it’s much more difficult in the suburbs in the summer. When you have no money, the climate isn’t friendly with you.”

Hidalgo’s wider vision for the city itself includes three significant actions around heat: turning schoolyards and courtyards into neighbourhood parks; adding urban forests to landmarks such as city hall (Hôtel de Ville de Paris) and Palais Garnier as well as planting 170,000 trees along many of the city’s biggest intersections and boulevards; and turning as many drivers into cyclists, pedestrians and transit users as possible. Proponents point to the measures as quality-of-life improvements: imagine city life with fewer noisy engines and more congenial, pedestrian-first urban spaces, all lined with parks, green roofs and trees. Hidalgo’s ambition is sizeable; she wants half the city to be covered in vegetation or permeable pavement, including parks and green roofs. The wider regional vision of increased transit and bike lanes that connect banlieues to the city centre would improve access to opportunity and decrease carbon emissions at the same time.

Paris’s plans are especially focused on areas in the north and north-east parts of the city, such as Goutte d’Or, a heavily North African neighbourhood, and the area around the massive Gare du Nord train station, which demographic data and maps of public parks point to as lacking adequate, accessible spaces to cool off. The city’s Oasis programme (which stands for Openness, Adaptation, Sensitisation, Innovation and Social ties) seeks to turn 770 schoolyards (a total of 80ha) into parks by 2040 and may pay the most dividends. According to Regina Vetter, network manager for the global Cool Cities Network at C40 Cities, these parks will create their own “cool islands” within the overall urban fabric.

In the long term, Paris wants to invert typical notions of city planning, according to Paul Lecroart, a senior urban planner for the Paris Metropolitan Region Planning Agency. Transit and metro rails are being expanded to the banlieues, including the 200km-long Grand Paris Express project, with the aim of delivering levels of service that match downtown. Regional development will be focused around new and existing transit stations, and public-housing estates will be rebuilt in an attempt to encourage mixed-income neighbourhoods. Hidalgo even wants to convert the Périphérique highway, a ring road around the city proper, into an at-grade boulevard and parkland to help physically and symbolically connect Paris with its surroundings. The Parisian leader doesn’t have final say over the policies enacted in the suburbs, but by pushing for more sustainable transit opportunities, she hopes to make a regional impact.

While many cities have made heat mitigation a priority in the past five years, the perspective really began to shift in Paris back in 2003 after a lethal summer heatwave killed 15,000 people in France, including 500 in Paris alone. High evening temperatures proved especially deadly for the elderly.

A challenge in adapting a city like Paris to warmer days is the building stock. Classic apartments and 18th-century buildings, shutters and all, were built for a cooler era, and adding upgrades, green roofs and retrofits is expensive and challenging due to regulations. The public housing built in the 1960s in the suburbs has a different type of problem: it’s too flimsy, letting the heat out in the winter and trapping it in the summer.

The aim in Paris is to create a patchwork of green spaces around the city and surrounding the metro region, says Vetter. It’s the 15-minute concept but for heat relief.

Already, Parisians can download an app called Extrema, enter in any medical conditions that might be exacerbated by high temperatures, and wait for warnings about high-heat days alongside maps and directions to nearby cool sites. The city has more than 800 cooling centres, pools and green roofs mapped via the app. These services and resources have kept recent heatwaves from having as lethal an impact as the one in 2003.

But to truly create a more resilient city, adding parks and rethinking urban planning needs to happen on a regional scale. Lecroart says cuts in municipal budgets and less support from national leaders mean Paris has to “find ways to do more with less money”. Over time, the city’s current response system will fall short of the systemic changes needed to protect Parisians from a warmer future.

“We need to rebalance urban development,” he says. “It’s challenging because we need the support of the national government, but they have so much difficulty imagining another system.”

This article is part of a reported series focused on how increasing numbers of high-heat days are affecting cities around the globe. Read about the situation in Mumbai and in Los Angeles, and come back to City Monitor in the coming weeks for additional reports.