Republicans are already lining up to tear apart President Joe Biden’s $1.9trn stimulus proposal, using familiar attack lines about a so-called “blue state bailout”. This indicates that a push to deliver federal aid to lower levels of government will continue to be debated along partisan battle lines under the new administration.

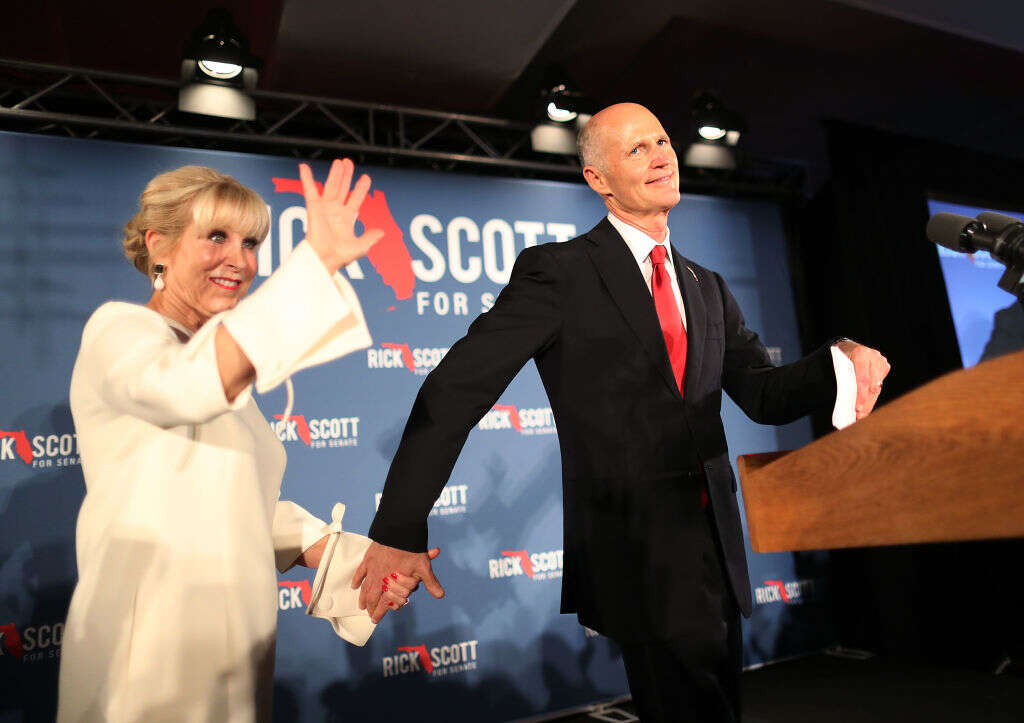

Last week, after Biden proposed $350bn in aid for states and localities, Florida Senator Rick Scott summed up his case for opposing it. He told Fox News that state and local aid “makes no sense” and that “we shouldn’t have Florida taxpayers bailing out New York”.

He wasn’t the only Florida Republican making these claims on Fox.

“This is a bailout package for blue states for their bad policies, for their lockdown policies,” said Congressman Michael Waltz, who represents a swath of central Florida. “Our numbers aren’t any worse or aren’t any different than California and New York, but, you know, now they have these massive state budget deficits.”

These arguments are not grounded in fact. While some states have avoided the apocalyptic budget scenarios they feared in 2020, when forecasters were scrambling to model an unprecedented crisis, the situation is still quite bleak. And Florida is one of the states set to benefit the most from further federal aid.

Data from the Urban Institute shows that Florida has seen one of the sharpest falls in tax revenue in the US, with a roughly 12% decline when comparing March-November of 2019 with the same period in 2020. (December data is not yet available.) That puts Florida’s shortfall in the top five among states in percentage terms.

Florida’s deficit for the budget beginning in July 2021 is projected to be at least $2.1bn. The state got hammered not only by a decline in tourism but because it does not have a sales tax on online transactions.

California’s proportional decline is far more modest, although the sheer number is greater because the state’s population and economy are larger. Last November, it was actually projected that the state will have a budget surplus, although the medium-term budget outlook in the US’s largest state is less positive.

An array of reporters and analysts have also highlighted that the state and local budget shortfalls are not as apocalyptic as was feared earlier in the pandemic. The massive federal stimulus programmes of 2020 are the chief reason for this relatively sunny outlook, as well as the inequality of a recession that has preserved many white collar, professional-class jobs.

Despite headlines touting the relative success of some state budgets in weathering the storm, the overall picture is still dark.

Between March and November (the latest data available from the Urban Institute), total tax revenues across the country were down 3.3%, or $23.5bn, in comparison with the same period in 2019. More than half of the states, 29 to be precise, reported revenue declines. (Data for a handful of states is not available yet.)

“If there was no pandemic and no recession, those revenues should have been 3% to 5% above the levels observed in 2019,” says Lucy Dadayan, senior research associate at the Urban Institute. “It’s not just a $23bn decline; it’s a lot more. And we still don’t know how things will turn out, because we see a historically high level of disagreement among economists in terms of their forecasts. It’s still highly uncertain.”

The budget hole highlighted by the Urban Institute also undersells the challenges facing state and, especially, local governments. Spending has shot up substantially as the public sector has had to meet unprecedented and expensive needs like securing protective equipment for employees, regular cleaning of state buildings and requisitioning hotel rooms for safe social distancing of the unhoused.

The only reason state and local finances aren’t worse is because of the massive stimulus commitments of 2020.

“The revenue hit hasn’t been as big in some states as was anticipated, but that doesn’t mean the picture is rosy,” says Amanda Kass, associate director of the Government Finance Research Center. “The spending side of it is getting completely left out. Even if a state’s 2020 revenue was more than 2019, is it sufficient to meet the need that now exists?”

Local governments are in an even more vulnerable position. In addition to mounting service cost increases, they have narrower tax bases and even anaemic ones in many cases. They are also at the whim of their states, two of which (Michigan and New York) have already cut aid to localities to help balance their state budgets. Meanwhile, most cities rely heavily on property taxes, which don’t react quickly to downturns like sales or income taxes do. Research from the National League of Cities found that the low point for municipal revenues in the past three recessions didn’t occur until two years after the beginning of the downturn.

Even for those states that have come out of 2020 strongest, like Vermont, policymakers still fear that volatility and uncertainty will be the norm this year, too. The pandemic is only worsening, more infectious strains are spreading, and joblessness continues to surge, as another 900,000 people applied for unemployment during the last week of Donald Trump’s presidency.

All of this is to say that the “blue state bailout” rhetoric of politicians like Scott bears no relation to reality. The only reason state and local finances aren’t worse is because of the massive stimulus commitments of 2020. There is little about 2021 that suggests now is the time to ease up on such support.