When the US economy was thrown into a recession with the onset of the coronavirus pandemic, an existing housing crisis rose to a fever pitch. In a country where already close to one million evictions happen each year, massive waves of layoffs suddenly left thousands of Americans unable to make rent and put them at risk of losing shelter in the middle of a global health crisis.

Governments at the state, local and federal levels took steps to temporarily halt evictions during the emergency. Congress included protections in the CARES relief act passed in March, and the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) in September issued further guidance to prevent expulsions through the end of the year. A number of states and cities offered even stronger safeguards for renters. But most remaining state and local moratoriums are set to expire in the next few months, threatening to bring a tidal wave of evictions to millions of households across the US.

A recent analysis from the Eviction Lab at Princeton University found that state and local moratoriums, working in tandem with federal measures, significantly reduced the rate of expulsion filings in US cities this year. The impact of the policies varied depending on what part of the process they specifically applied to, but the data shows that these state and local measures made a material difference in whether people were forced out of their homes.

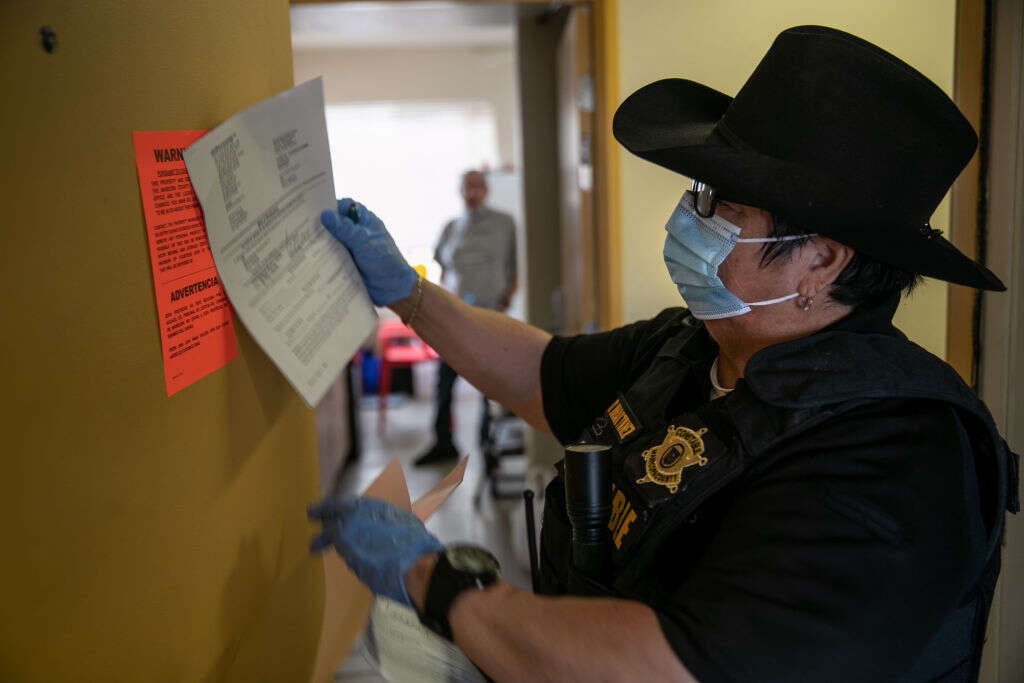

In general, when a landlord files an eviction against a tenant for non-payment, there are a series of steps that must follow: notice is given to the tenant, the motion is filed in court, a hearing is held, a judge issues a decision, and finally a sheriff’s office is authorised to remove the tenant. Different places targeted different steps of this process in their efforts to halt evictions: some said landlords couldn’t give notice to evict, others allowed court filings but paused hearings.

In their analysis of eviction filings from 25 US cities, the researchers found that when landlords were allowed to advance further into this process during the pandemic, more expulsions happened. In places that stopped evictions at the initial notice stage, the number of filings was less than 25% of historical averages. In Phoenix, the only city evaluated that halted expulsions at the final enforcement phase, filings were up to 37.6% of the historical average. While still well below historical norms, this rate is significant in the midst of a deadly pandemic; research has shown that where evictions are permitted to happen, people are at greater risk of contracting and dying from Covid-19.

“Generally, the clear benefit of the state and local measures is that in many cases, they did freeze notice and filings, which the CDC explicitly does not,” says Peter Hepburn, a research fellow at the Eviction Lab who co-wrote the report.

Hepburn notes that receiving an eviction notice on the door can be enough to make some people leave, even if they don’t legally have to at that time.

“The filing stage can be really significant in whether people are actually leaving their homes,” he says. “Forcing someone from their home is awful, but too many people are fixated on that as the culmination of the process, when the reality is that many people leave their homes much earlier.”

The researchers also found that as soon as temporary protections were lifted, eviction filings shot up, especially in places where expulsions had been suspended at earlier stages. On average, in cities where evictions were stopped at the notice stage, filings rose to 64.7% of historical averages within two weeks of the removal of protections. The Eviction Lab keeps track of state-level moratoriums in its Covid-19 Housing Policy Scorecard.

Crucially, none of the eviction protections offered at the local, state or federal level offer rent relief or forgiveness – they only postpone the consequences of unpaid rent. Meanwhile, the accumulating debt is ballooning. A separate analysis of four US cities found that the average amount of back rent people owe has nearly doubled in the past year. In New York City, the median claim amount was nearly $5,000 in November, up from $2,500 before the pandemic. The geographic distribution of these claims does not suggest that landlords are suddenly filing evictions against higher-income tenants who pay more in rent but rather that greater numbers of low-income tenants are owing more and more as the moratoriums kick the can further down the road.

“I think there is a lot of reason to expect things to get worse,” Hepburn says. “There will be a number of households that are so behind, there’s no way for them to catch up.”

In the absence of federal rental assistance, many Americans will be facing a dire situation when rents come due. But in the meantime, state and local policies have an opportunity to bridge the gap between shelter and homelessness while the virus spreads.

“Anything that drops eviction filings substantially is a good thing,” Hepburn concludes.