“It can’t be just business as usual. This has to signify change,” Sir David Adjaye says. It’s a sentiment that is profoundly on point; a timely and perfectly delivered message for a world striving to rebuild itself, and not just from a head-spinning mass pandemic.

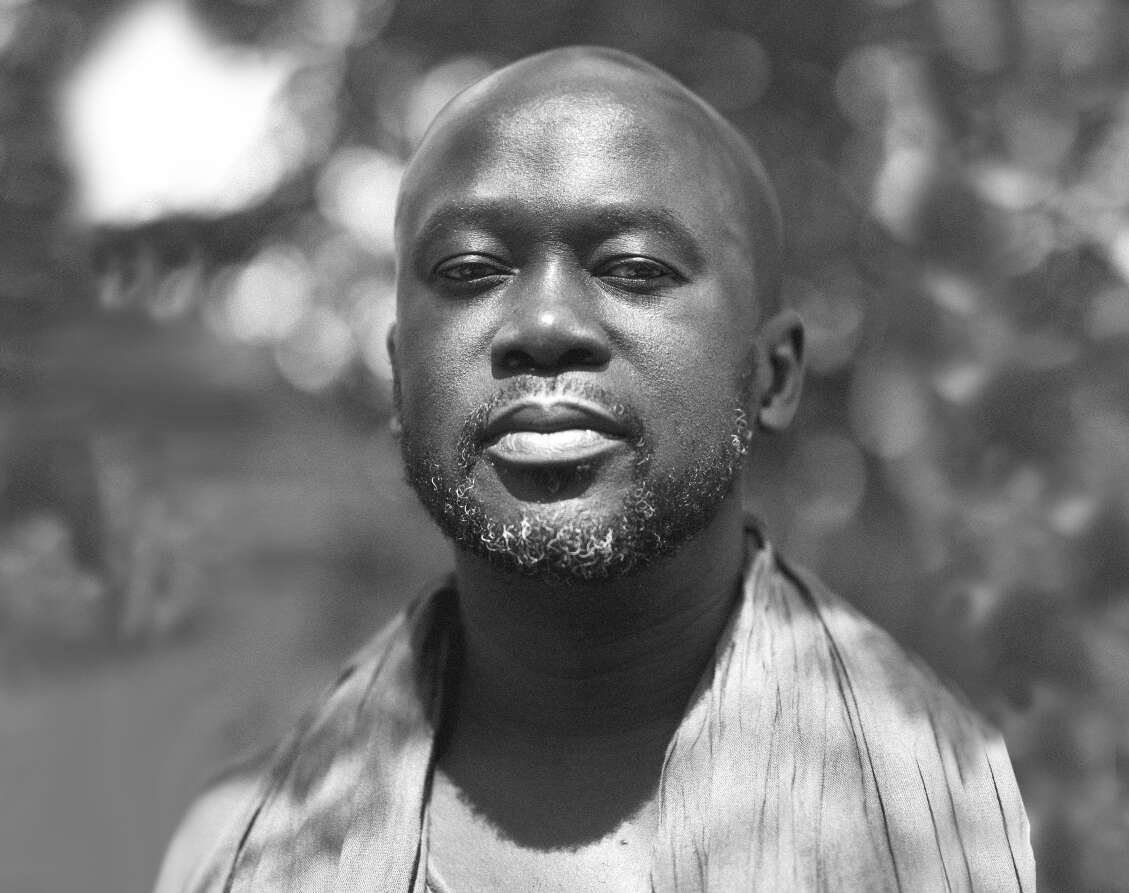

The Ghanaian-British architect is talking about his career highlight to date: the RIBA Gold Medal. Not only is Adjaye an incredibly young recipient – he turns 55 in September – but the first black man to receive the accolade. “RIBA have said that they’re proud of the fact that there is somebody of colour that they could give this award to,” Adjaye says, “but [they] also realise that they’ve got a lot to do to support communities of colour in the built environment, in terms of education, and supporting the excellence that’s required. It’s not just done by the individual. It’s a collaborative thing.”

Where to start. Adjaye is, after all, as iconic as they come. Alongside his most recent award, one can add an OBE and a knighthood along with enough newspaper and magazine column inches to sink a small boat.

Eloquent, stylish, media-savvy, he has all the qualities of a ‘starchitect’, but he is not interested in playing it safe. Far from it. “I don’t want to do things that just get me from A to B. I’m interested in things that really move the needle,” Adjaye says.

In fact, he has been highly critical of a generation of ‘celebrity architects’ that have used tremendous sums of money to produce public-facing buildings that say very little. It’s a feat Adjaye seems incapable of doing. Even a cursory mention of his days designing houses for the likes of Chris Ofili, Alexander McQueen and Juergen Teller is swatted away.

“Well, it’s funny, because I think there was maybe one celebrity who was Ewan McGregor. I actually made my early career doing projects for artists, because normal people didn’t want to commission me,” he says with a smile.

Make sense, make form

After founding his eponymous firm in 2000, the Tanzanian-born architect has pursued a diverse range of high-profile projects. His portfolio runs the gamut from a mixed-use affordable housing development in Harlem, and a learning centre in Lewisham – named Blueprint for All – created in honour of murdered architectural student Stephen Lawrence, to the Moscow School of Management in Skolkovo (2010) and the Aishti Foundation, an arts, leisure and shopping centre in Beirut (2015).

A profound appreciation for historical themes and cultural symbology permeates all of his work. In Moscow, he drew on the work of Russian avant-garde artist Kazimir Malevich. In Beirut he wrapped the Aishti Foundation in geometric patterns reminiscent of the mashrabiya, the latticed wooden facades common in traditional Arabic architecture.

How does he choose which of these narratives to play on and which to discard? “That’s the moment I call the authorial choice,” he says. “Something has to make sense to me to make form, otherwise I’m not inspired. So I’m the vehicle [for] the story and then if it’s accepted by the client then that’s a kind of confirmation of its relevance. It’s a sort of funny democracy really.”

For his most high-profile building, The Smithsonian National Museum of African American History and Culture, Adjaye was influenced by his own personal experiences growing up in Africa. Born in Dar es Salaam, Tanzania, as the son of a Ghanaian diplomat, he lived a nomadic childhood. By the time he arrived in Hampstead, London, as a pre-teen, he had lived in Kampala, Nairobi, Cairo and Accra.

His design for The Smithsonian reflects a desire to put African culture “on a pedestal”. Clothed in burnished bronze, the jagged three-tiered structure draws on the shape of a Yoruban caryatid, a traditional West African column with a corona at the top. Such artisanship was a hallmark of the great empires of the Yoruba in Nigeria and Benin, great civilisations that, Adjaye says, have “been made invisible, because of the way history has been written”. Subtle patterns in the ironwork also nod to the craftsmanship of a former African-American slave from Charleston, South Carolina.

It remains a project of staggering complexity: the pain and adversity endured by African Americans throughout history is evident, but it was Adjaye’s wish that the narrative be reclaimed; that such hardship might also be elevated and turned into a paean for progress and triumph against crushing adversity.

It’s a building that has only acquired more relevance during a time in which racial inequalities and colonial history are being placed under the microscope on both sides of the Atlantic. In the case of the Yoruba and the artisanal craftsmanship of former slaves, it presents a sophisticated culture that has been wilfully neglected. By illuminating that legacy Adjaye sees the Smithsonian as a direct rebuke against the insular “fiction” of white supremacy.

“We thought we were in a different world when it was being built, a world where the idea of the superiority of races was being flattened and we were talking about the common humanity in everyone only to have that slingshot flicked back in our face,” he says. “Still, what has been amazing is to see that building being used as a site of protest, a site of affirmation, it’s kind of a demonstration of precisely why architecture matters.”

Rebuild to reclaim

As his work has grown in stature, so Adjaye’s focus has shifted back to Africa. In 2018 he revealed designs for The National Cathedral of Ghana, which will host a 5,000-seat auditorium beneath a concave roof constructed beside the city’s Osu Cemetery, set within 5.5 hectares of landscaped gardens.

The architect describes the project as a “study on identity and nation-building” in a country where church and state are not separate entities but mutually entangled, integrated into the fabric of cultural life. It’s a theme Adjaye is also exploring in his Abrahamic Family House in Abu Dhabi, which takes the form of three cubic temples designed to promote peaceful dialogue between the three Abrahamic faiths.

More recently, Adjaye’s focus has shifted to the Edo Museum of West African Art (EMOWAA), based in Benin City, which aims to house repatriated objects currently on display in European museums. If the Smithsonian was a battle cry against one-dimensional colonial narratives, the Edo Museum is about enabling self-realisation after what Adjaye terms a lasting process of “erasure”.

“We propose that this museum is the beginning,” Adjaye explains. “That it is a required reclaiming of the architectural heritage of these extraordinary civilisations as the backdrop of these communities and not as a fiction in some virtual space or imagination.”

Societal memory continues to be a source of fascination in his work – both the narratives that are perpetuated by the retelling of collective stories and the blind spots that can emerge as a result. It’s a passion that has grown more vociferous as fake news has created a world where facts are no longer concrete, but fluid, open to interpretation or simply there to be derided or ignored.

Located in Westminster, a stone’s throw from the Houses of Parliament, Adjaye’s UK Holocaust Memorial and Learning Centre is a collaboration with Ron Arad Architects and Gustafson Porter & Bowman, and a testament to the architect’s belief that architecture can combat lies. More specifically, it has been calibrated to challenge a perception among 5% of UK adults that the Holocaust did not happen.

Built on a mound of earth in Victoria Tower Gardens, London, the entrance comprises 23 bronze fins with the gaps between them representing the 22 countries where the Holocaust destroyed Jewish communities. The fins then act as gateways, leading visitors to a learning centre built to use the facts of the Holocaust to explore anti-Semitism, extremism, Islamophobia, racism, homophobia.

It has not been without controversy. Guardian critic Rowan Moore described it as suffering from a “flawed brief”. David Aaronovich of the Times found it cold. Others have criticised its location on a much-loved public space, some even its close proximity to the heart of government.

Challenging perceptions

Such criticism has not deterred Adjaye one iota. He continues to be vocal about the powerful role memorials serve in public and cultural life, arguing that they need to be rethought for contemporary times. In an increasingly polarised world where history is being contested like never before, well-meaning blocks of stone are not enough. Instead, the architect advises “against just repeating the past, just because we know what it looks like”. His memorials, he says, are deliberately focused on “how the body moves” within these spaces.

Sometimes of course learning from the past means tearing down statues to once venerated figures. On the subject of whether or not the statue of British imperialist Cecil Rhodes should be removed from Oriel College, Oxford, Adjaye is unequivocal.

“I think what he did was to the benefit of Britain, but to the detriment of a whole race and civilization. I think it’s deeply problematic,” he says. “Put him in a museum, put him in a cupboard, but don’t celebrate him.”

The conversation concludes with a discussion of the impact the global pandemic has had on architecture. Somewhat quintessentially for an architect committed to questioning and reinterpreting the past, Adjaye believes that the Covid-19 crisis will reshape the industry for the better.

“It’s allowed architects to see that we can’t build blindly. That the climate agenda is so phenomenally important. We’ve seen how the earth resuscitates when we all stop our nonsense,” he says. “I just think that the whole world has shifted. And so we have to make the world again. I mean, that’s the kind of wasteful and beautiful part of the architecture. We think we’ve done it, and then we have to redo it. Actually, it’s the most inspiring thing.”

This article originally appeared in LEAF Review.