Sandra Ellington has lived in Cleveland all her life. At the beginning of the 1960s, the decade she was born, the city was still among the ten largest in the US and a pride of the Midwest’s manufacturing belt.

She says the Cleveland she grew up in was no paradise, but there were still opportunities for young people. Ellington fondly remembers attending her local elementary school, where students were provided with seeds to grow their own fruit and vegetable gardens. She knew the names of the garbage men who served her block and the city workers who swept her street.

Ellington even recalls how when she was young, her neighbourhood would have parades down the main street, paid for with a little help from the city and a lot of volunteer hours. She doesn’t quite know when they stopped throwing them. Maybe it was around the time of Cleveland’s 1978 default, the first of any major US city since the Great Depression.

“I loved it because there were things that children can be proud of, something they can hold on to,” says Ellington of the city services she recalls from her younger years. “It didn’t have to be a big thing. It was just in your community where you stay, and it makes you feel proud. You didn’t have to live in the suburbs to have small things like that. We can have it right in our own city.”

But that city Ellington remembers is largely gone, gnawed down to the bone by some of the most inexorable forces in US history: anti-Black racism, deindustrialisation, population decline, state-level interference and aggressive suburbanisation.

To deal with this staggering social crisis, Cleveland has largely been left on its own.

City services began being slashed in the 1970s, then federal aid to cities fell dramatically in the 1980s and never recovered. Cleveland’s finances were ravaged again by the Great Recession – its neighbourhoods were devastated by foreclosure, and then, in 2012, Republican Governor John Kasich cut state aid to cities by half.

Now, as the Covid-19 economic crisis unfolds, policymakers and academic experts fear that further cuts are coming. In the absence of a commanding Democratic victory in the 2020 elections, substantial federal aid is considered unlikely. Without help, there will be little option but to cut deeper.

There are dozens of US cities that have been left behind in similar or even worse ways. Declining big cities like Detroit and Cleveland pumped a lot of development and political capital into building up downtown office districts, relying on white-collar professional commuters to counterbalance the loss of manufacturing. They at least also have robust hospital and university sectors. Smaller ex-industrial cities – like Flint, Michigan, or Chester, Pennsylvania – and declining suburbs like East Cleveland are in even more dire straits. And their ranks are swelling. Just before the pandemic swept across the country, a Wall Street Journal analysis found over a quarter of US cities expected to see their general funds shrink in 2020.

“Whatever you think of defunding the police, we, quite frankly, have done that already,” says Eric Scorsone, a professor of local and state government at Michigan State University and an adviser to the mayor of Flint. “The difference is that the defund-the-police movement wants to fund social services. We haven’t done that, either.”

As the economic calamity of the pandemic continues to unspool, the danger is that larger cities will suffer the spiralling devastation already faced by places like Flint or Camden, New Jersey. Like many US cities, Cleveland has spent the past half-century or more skipping from catastrophe to catastrophe. It can ill-afford another one.

Austerity feeds on the US’s unique form of urban decline

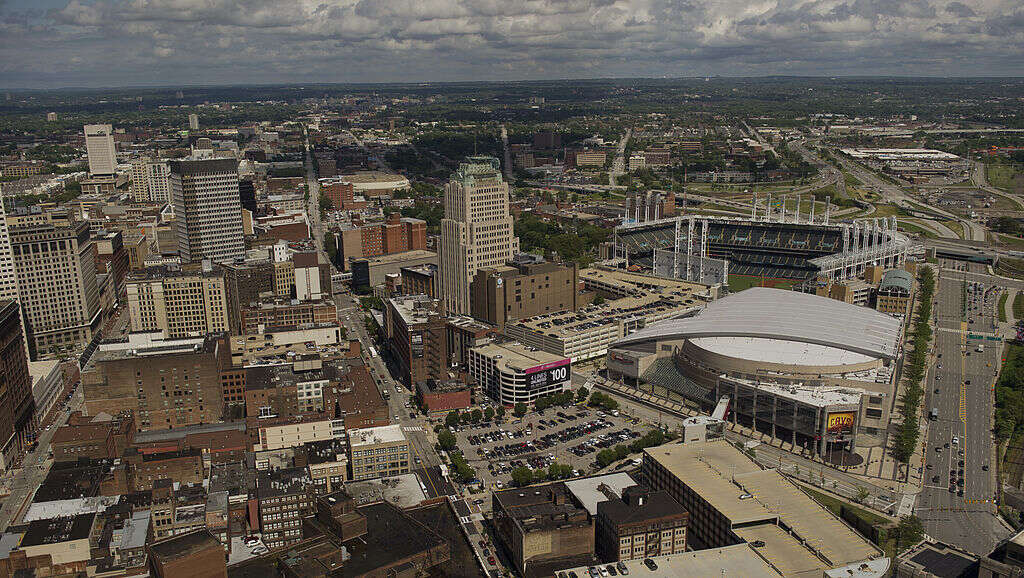

As Cleveland entered 2020, the city was looking comparatively stable. Although both the municipality and Cuyahoga County, where it is located, had continued to lose population over the previous decade, the decline appeared to be slowing. The gamble city leaders had made on expanding the downtown’s amenities and jobs seemed to be paying off, with population growth there being one of the few regional bright spots.

The city budget seemed to be doing relatively well too. Mayor Frank Jackson projected a $46m surplus at the end of 2020, a few million more than the city managed the previous year. He believed the city could handle a two-year recession without layoffs.

But looking beneath the surface, the fundamentals do not appear as strong. Cleveland’s finances have been stuck at inadequate levels for years: its operating budget in 2019 was, adjusted for inflation, roughly the same size as it was in 2004 (although the population is smaller after 16 more years of decline). The budget looks healthy now only because so many programmes and personnel have been cut over the years.

“[At the beginning of this year] a lot of Michigan and Ohio cities were financially better off, quite frankly, because we cut a lot of stuff and services are way down,” Scorsone says. “Austerity has been going on at least ten years, and you could argue over 30 or 40 years. Most of these Midwestern cities are very much lacking in infrastructure, in police, in fire, in basic public services.”

As Cleveland has been racked by waves of tragedy and catastrophe, the surrounding region and the state have done little to help. Revenue sharing from state to local governments in Ohio have not increased in inflation-adjusted terms since 1970. It’s in that context that aid from the state of Ohio shrivelled under Kasich. In the wake of the Great Recession, as federal aid from the Obama administration’s stimulus package wore off, further financial assistance to cities was cut by Republicans in the state capital. Cleveland lost what would have been $30m annually over much of the past decade.

Now, as Covid-19 looms over next year’s budget, and taking into consideration Ohio’s own looming budget crisis, local observers have little to hope for Columbus. In the Ohio Legislature, where anti-urban legislation is the norm, Republicans expanded their majorities in the 2020 elections. Cleveland gets the majority of its budget from income taxes, and the vast majority of these revenues come from suburban workers who commute into the city.

Or it did before March, anyway.

Now some Republican legislators, and conservative think tanks in Columbus, have been arguing for allowing remote workers to keep their income taxes in their home municipalities. Such an outcome would eviscerate what remains of Cleveland’s budget.

“If they do that, they will devastate all the urban areas in Ohio,” says Michael Polensek, who has served in the Cleveland City Council since 1978. “You will have an increase in crime, in violence, in homicides. You will have more disinvestment. No one with any fricking common sense – I’m being very polite here – would support that.”

Republican Governor Mike DeWine signed a law at the beginning of the pandemic that was meant to prevent this very outcome, at least during the course of the emergency. But even if conservative lawsuits and legislation to redirect income tax revenues in the short term fail, there is a looming threat of white-collar workers’ no longer commuting to jobs downtown as often.

Polensek hopes Cleveland won’t be as grievously wounded by next year’s budget as other major cities, because it started 2020 with a surplus. There have been no layoffs yet – although no new hires or pay increases, either – and it won’t be clear until January if Jackson and other local officials will propose cuts. But outside experts fear the worst. As weak as city services in Cleveland are today, there is still more that could be lost.

“Cleveland’s already not doing well, but I’m sure they’re going to be doing much worse soon,” says Hannah Lebovits, assistant professor of public affairs at the University of Texas at Arlington. “East Cleveland is an awful case study for what could come next. They have cut almost everything. Their city has been gutted, they’ve lost most essential services, although they still do have police. It’s pretty horrifying.”

No one has a rust belt like the US

It would be easy to solely blame capital flight for Cleveland’s weakened state in the face of Covid’s onslaught. There are rust belts in every wealthy nation, where the industrial economy used to reign but now the empty hulks of mills and mines dot the landscape. But there is a crucial difference between the US and the rest of the world. In none of these other regions has the loss of manufacturing, or its unionised workforce, resulted in the utter social devastation found in the US Rust Belt. Huge swaths of major cities have been abandoned, while many of those who remain suffer poverty and deprivation on a scale unseen in other wealthy nations.

There is nothing like Detroit or Cleveland in any other advanced nation because there is nothing like the US’s racialised geography in any other advanced nation.

University of Toronto professor Jason Hackworth describes the results as “organised deprivation”, where cities with large Black populations have been systemically undercut by racist public policies – like redlining and exclusionary zoning – and social trends like white flight. These societal norms have brought Cleveland to its knees. At the beginning of the 1960s, Cleveland was the eighth-largest city in the US. Now it isn’t even in the top 50. Since its population peak in 1950, it has lost almost 60% of its residents, and 34.6% of the city lives in poverty.

“In my work, I emphasise how the pathologisation of Blackness mobilises decline in ways that we attribute to deindustrialisation,” Hackworth says. “That’s not to dismiss deindustrialisation, but there is an unevenness to how steep the cliff was and whether cities were able to turn a corner that aligns very closely with the racial composition of those spaces.”

In the 1940s, like many industrial hubs, Cleveland attracted African American workers from the South for the abundant jobs available in the wartime economy. Black Southerners continued moving north after 1945, fleeing the racial tyranny of the Jim Crow states.

Between 1940 and 1960, Cleveland’s Black population tripled in size to 250,000. At the same time, both capital and the white population began fleeing the city, and walls were erected to make it difficult to follow them. Between 1950 and 1965, 242,000 white people moved out of Cleveland. In the 1970s, almost a quarter of the city’s population vanished.

Exclusionary zoning and restrictive covenants blocked the Black population from following white residents and jobs into the suburbs. Even Shaker Heights, a well-to-do enclave on the city line with an integrated middle-class population, acted to block residential spillover from neighbouring Cleveland communities. Policymakers in the suburb of 30,000 purchased homes at sheriff’s auctions to prevent in-movement from the city, demolished the cheapest homes in their municipality and eventually erected street barricades to prevent drivers from crossing into the town from the Mount Pleasant neighbourhood (where Ellington now lives).

The hyper-segregation of Cleveland’s East Side resulted in falling home and land values. Predatory landlords moved in, extracted profits from their properties and then abandoned them and moved on to the next shambolic houses. These neighbourhoods were targeted, too, by the predatory lenders who fuelled the mortgage crisis – which also left a swath of abandoned homes in its wake.

“When I came into city council in January 1978, I didn’t know what an abandoned house was,” Polensek says. “Now I deal with them every day, and I have one of the better wards in the city.”

For Ellington, it seems like the city’s demolition campaigns are never-ending – and she isn’t wrong. Cleveland went all-in on urban renewal after World War II, putting more acres in the program than any other city. But that was just the beginning. In the mid-1970s, the city began tearing down thousands of homes a year in Black-majority neighbourhoods. In the 1980s, they tore down 19 houses for every new home permitted.

Ellington’s neighbourhood of Mount Pleasant is on Cleveland’s East Side, and the foreclosure crisis left deep scars on her community. Despite the national scope of that predicament – caused by financial deregulation and predatory lending practices – the city has been left to deal with the aftermath on its own. Most of the city’s response has amounted to demolishing abandoned property. Almost a decade on, the campaign is ongoing.

“They’ve been tearing down the housing, but they haven’t replaced it with anything,” Ellington says. “We just have a bunch of empty lots. I understand that the houses had to go because it was an eyesore, but in the same token, you need to have, like, a plan.”

From Ellington’s perspective, all those empty lots could be turned towards a higher social good with a little effort – and a lot more public resources. When she switches from the bus to the light rail downtown to get to her job as a janitor at the Cleveland International Airport, Ellington cannot help but notice people sleeping on grates and manholes.

“With all the homelessness, you’d think they’d build some affordable homes on those lots,” Ellington says. “That boggles my mind. It really bothers me because those are my neighbours. Those are the people I see every day.”

“People want to pretend like there’s nothing we can do”

All of this ugly racial history devastated municipal finances. Just as Cleveland became the home of the vast majority of the region’s low-income population, with the residents in the most need of public assistance, it became less and less able to maintain services. But because of the perversities of the US’s regional governance – or lack thereof – when all those white households and businesses moved out of the city, they took their tax dollars with them. During the 1970s, hundreds of firefighters were laid off even as arson lanced through many inner-city neighbourhoods.

These kinds of outcomes are encouraged by the fragmented municipal boundaries common in many parts of the US. That makes it easy for a family with options and income to pick up and move a mile away from the central city and into a suburban municipality with more families of their class (and probably racial) background. They are incentivised to horde their property tax dollars and deprive resources from the urban centre, where social needs are more acute.

Contrast that with Canada in the 1950s, when many provinces combated the forces of suburbanisation and deindustrialisation by forming “metro” governments that encompass the central city and many of its surrounding municipalities. Borrowing took place on a regional or provincial level, while urban-planning and public-transit agencies were also orchestrated across municipal lines. As a result, urban public schools and municipal infrastructure did not atrophy as Canadians moved to the suburbs. When industry shifted to expansive greenfield sites at the periphery of the region, it made living downtown more pleasant without robbing the city budget of much-needed revenue. In Canada’s Rust Belt of Southern Ontario, provincial governments eventually forced the amalgamation of older cities with their suburbs.

In addition to advising Flint’s mayor, Michigan State’s Scorsone has also worked with policymakers in the European Union. He says the contrast between the Midwest and his work across the ocean is striking.

“There’s more of a sense of fairness when it comes to local government over there, a sense that resources need to be equalised,” says Scorsone. “Here, we’ve decided that if you have money, you get stuff. If you don’t have money, you don’t. People want to pretend like there’s nothing we can do about it. But these are choices being made to restrict these cities’ ability to function.”

For Ellington, the pain brought by the pandemic and Cleveland’s struggle to grapple with it are already clearly visible. Although she still has her job, she knows many people who have lost work during the pandemic-induced economic crisis. She hoped that the virus would unite people across the country, across political beliefs, across municipal lines. But so far, it doesn’t feel that way.

“I don’t want to see my city die. I love my city,” Ellington says. “And the fear of it dying just hurts my heart. When an individual loses their job, that’s less revenue for the city. I think about all of that, yes. I think about all those people not in the buildings [downtown]. We’ve got to figure something different out.”

Jake Blumgart is a staff writer at City Monitor.