For 125 years, a statue of the 17th-century slave trader Edward Colston stood in the centre of Bristol, ostensibly to commemorate the philanthropy he’d used his blood money to fund. Then, on 7 June, Black Lives Matter protesters pulled it down and threw it into the harbour.

The incident has served to shine a light on the benefits Bristol and other British cities reaped from the Atlantic slave trade. Grand houses and public buildings in London, Liverpool, Glasgow and beyond were also funded by the profits made from ferrying enslaved Africans across the ocean. But because the horrors of that trade happened elsewhere, the role it played in building modern Britain is not something we tend to discuss.

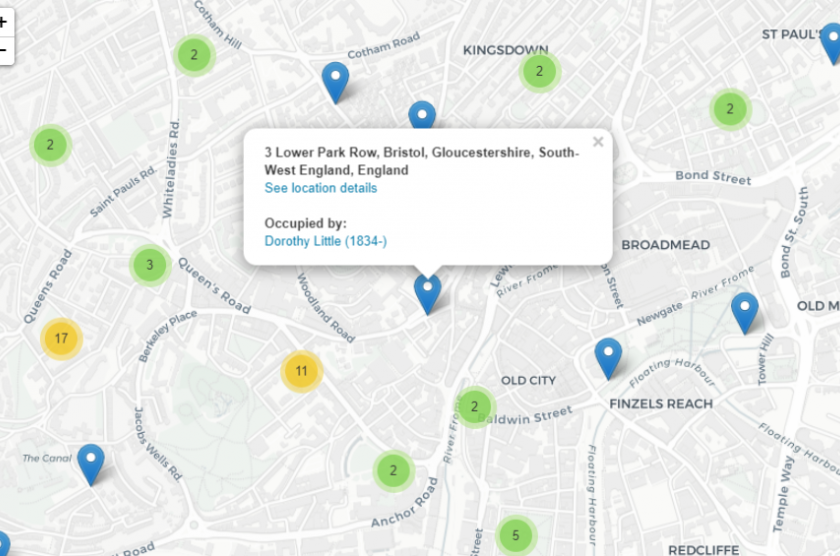

Now a team at University College London is trying to change that. The Legacies of British Slave-Ownership project is mapping every British address linked to a slave-owner. In all, its database contains 5,229 addresses, linked to 5,586 individuals (some addresses are linked to more than one slave owner; some slave owners had more than one home).

The map is not exact. Streets have often been renumbered; for some individuals, only a city is known, not necessarily an address; and at time of writing, only around 60% of known addresses (3,294 out of 5,229) have been added to the map. But by showing how many addresses it has recorded in each area, it gives some sense of which bits of the UK benefited most from the slave trade; the blue pins, meanwhile, reflect individual addresses, which you can click for more details.

The map shows, for example, that although it’s Glasgow that’s been noisily grappling with this history of late, there were probably actually more slave owners in neighbouring Edinburgh, the centre of Scottish political and financial power.

Liverpool, as an Atlantic port, benefited far more from the trade than any other northern English city.

But the numbers were higher in Bristol and Bath; and much, much higher in and around London.

Other major UK cities – Birmingham, Manchester, Leeds, Newcastle – barely appear. Which is not to say they didn’t also benefit from the Triangular Trade (with its iron and weaponry industries, Professor David Dabydeen of Warwick University said in 2007, “Birmingham armed the slave trade”) – merely that they benefited in a less direct way.

The LBS map, researcher Rachel Lang explained via email, is “a never-ending task – we’re always adding new people to the database and finding out more about them”. Nonetheless, “The map shows broadly what we expected to find… We haven’t focused on specific areas of Britain so I think the addresses we’ve mapped so far are broadly representative.”

The large number in London, she says, reflect its importance as a financial centre. Where more specific addresses are available, “you can see patterns that reflect the broader social geography”. The high numbers of slave-owners in Bloomsbury, for example, reflects merchants’ desire for property convenient to the City of London in the late 18th and early 19th centuries, when the district was being developed. Meanwhile, “there are widows and spinsters with slave property living in suburbs and outlying villages such as Chelsea and Hampstead. Country villas surround London.”

“What we perhaps didn’t expect to see was that no areas are entirely without slave owners,” Lang adds. “They are everywhere from the Orkney Islands to Penzance. It also revealed clusters in unexpected places – around Inverness and Cromarty, for example, and the Isle of Wight.” No area of Britain was entirely free of links to the slave trade.

You can explore the map here.

All images courtesy of LBS/UCL