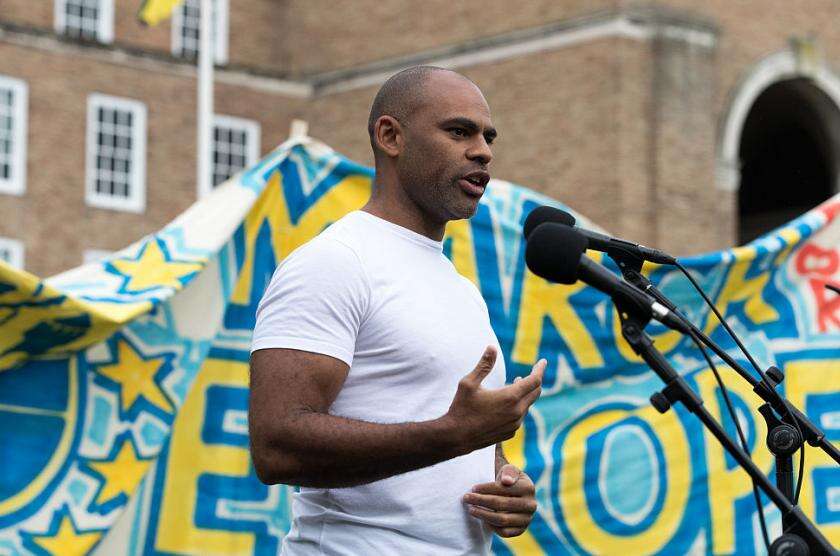

When the statue of 18th-century slave trader Edward Colston was torn from its plinth and dumped in Bristol’s harbour during the city’s Black Lives Matter protests on 7 June, Mayor Marvin Rees was thrust into the spotlight.

Refraining from direct support of the statue’s removal, the city’s first black mayor shared a different perspective on what UK Secretary of State Priti Patel called “sheer vandalism”.

“It is important to listen to those who found the statue to represent an affront to humanity,” he said in a statement at the time. “I call on everyone to challenge racism and inequality in every corner of our city and wherever we see it.”

48-year-old Rees, who grew up in the city, expanded on his approach to the issue in an interview with City Monitor, saying: “Wherever you stand on that spectrum, the city needs to be a home for all of those people with all of those perspectives, even if you disagree with them.”

“We need to have the ability to live with difference, and that is the ethnic difference, racial difference, gender difference, but also different political perspectives,” he added. “I have been making that point repeatedly – and I hope that by making it, it becomes real.”

What making that point means for Rees, in practice, is perhaps best illustrated by his approach to city governance.

Weeks after the toppling of Colston’s statue, a new installation was erected at the same spot featuring Jen Reid, a Black Lives Matter protester. However, the installation was removed, as “it was the work and decision of a London-based artist, and it was not requested and permission was not given for it to be installed”, Rees said in a statement.

Bristol may appear a prosperous city, logging the highest employment rate among the UK’s “core cities” in the second quarter of 2019. But it is still home to many areas that suffer from social and economic problems: over 70,000 people, about 15% of Bristol’s population, live in what are considered the top 10% most disadvantaged areas in England.

In an attempt to combat this inequality, Rees has been involved in a number of projects. He has established Bristol Works, where more than 3,000 young people from economically disadvantaged backgrounds are given work experience opportunities. And he is setting up another entity to empower the poor: “Launching a Bristol commission on social mobility is not only about social justice; it [should not be] possible for a modern city to leave millions of pounds’ worth of talent on the shelf just because the talent was born into poverty,” he says.

The mayor is also a strong supporter of the UN’s Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs), explaining that they offer a way to talk about sustainability within a framework of many issues, ranging from climate change and biodiversity to women’s issues, domestic violence, poverty and hunger.

“What we want to achieve as a city cannot be done as a city working alone,” Rees insists. “We don’t want to benefit only people inside Bristol, we want to benefit the planet, and the SDGs offer a framework for a global conversation.” His comments suggest that a vehicle should be launched that allows cities to work together, ideally with organisations such as the UN, the World Bank and the International Monetary Fund involved.

Greater collaboration between cities would be “beneficial in terms of economies of scale,” he argues, “as cities could get more-competitive prices when buying materials for building houses or ordering buses, rather than each city acquiring a few of them at a higher price.”

In an attempt to focus on the long term, Rees launched One City Plan in January 2019, setting a number of goals for Bristol to achieve by 2050.

Investing in green infrastructure to meet 2030 carbon emission targets spelled out in the SDGs is a key area, with the mayor noting that transport, mass transit and energy are important sectors looking for further investment and government funding. “The sooner we meet our targets, the sooner we will benefit from them, and invest in sectors that will provide people with jobs,” he says.

Jobs, especially following the outbreak of Covid-19, are of paramount importance to Rees. Bristol’s council wants to ensure that any government money given to the city will be quickly passed on to businesses to help prevent redundancies, he says, though given that mass job losses seem inevitable, reskilling options are also being looked into, such as through a zero-carbon smart-energy project called City Leap.

Another important area for investment in Bristol is affordable housing, with 9,000 homes already built under Rees’s term of office. “People could build a base for life with affordable housing, [and this would mean] their mental health would be better because they have a safe place,” he explains. “Children in families that have a home that is affordable are more likely to [be] able to eat and to heat, [and they are more likely to enjoy a] better education.”

Taken in the round, Rees’s agenda for Bristol is its own blueprint for shaping history. The Colston statue now lies in safe storage, with a local museum likely to play host to the controversial monument. But the Black Lives Matters protesters were fighting for a fairer, more equal future, and it is here where Rees is determined to deliver.