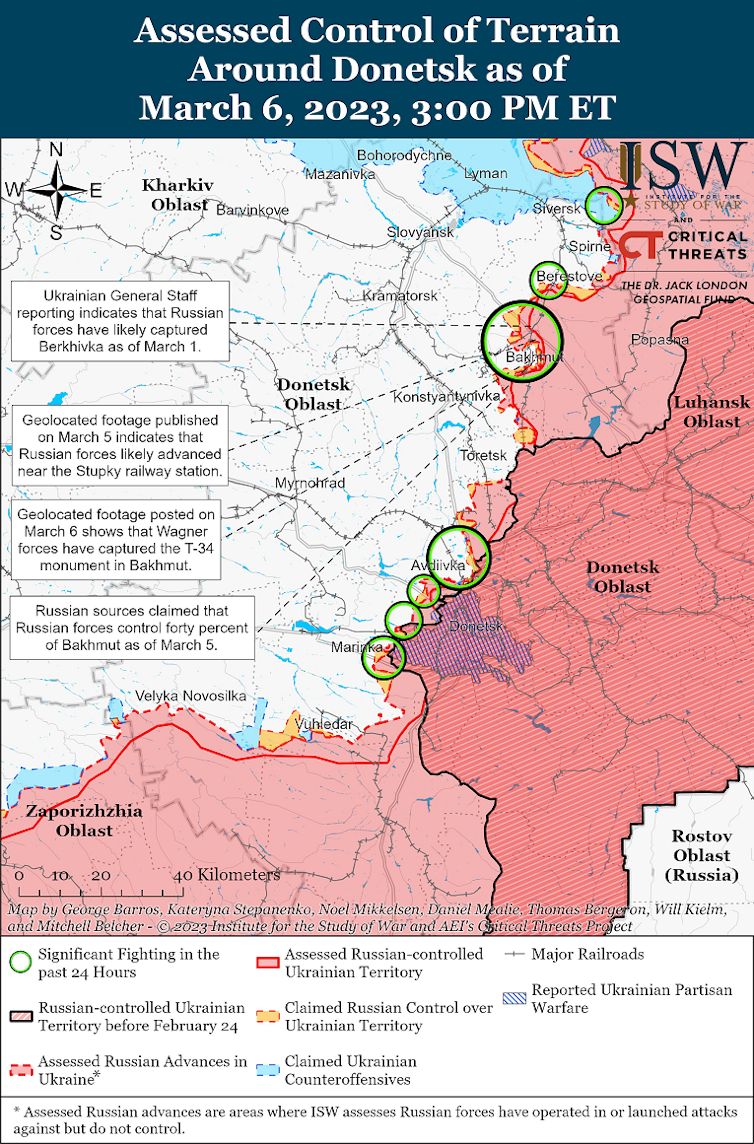

With winter coming to a close in Ukraine, Russia is making a series of advances in the eastern Donbas region, with a primary aim of capturing the city of Bakhmut. While the city itself has some (limited) strategic significance as a regional transport hub, neither its symbolic nor material value justifies the price that Russia is paying.

Wave after wave of Russian forces has been thrown into the same sector of the frontline, with a heavy cost being paid for modest progress.

Weather is playing its part in this. With Vladimir Putin’s special operation having lasted a year already, Russia’s war machine is again encountering the same conditions that frustrated its initial advances back in 2022. The spring thaw, or rasputitsa, brings mud and rain, restricting freedom of manoeuvre and confining most movement to main roads and rail networks.

The spring thaw has historically dictated the pace of military campaigns in the region. In the past, rasputitsa spelled disaster for the Mongols, Napoleon’s grand army, and even played a pivotal role in the second world war, slowing the German push towards Moscow in 1941.

Of course, the mud has no allegiance. It blunted the Soviet counter-offensives of the subsequent year. There is little need to look at distant history to understand the significance of spring weather conditions, however.

The wet conditions, along with the poor state of Russia’s land forces caused Russia’s initial push for Kyiv last year to be conducted along major highways. The risk of getting bogged down off-road contributed to Russia’s decision to send lengthy columns of tanks and other armour advancing along main roads towards the capital, on which the Ukrainians able to inflict heavy losses.

Many vehicles were lost or abandoned. It’s fair to say that weather conditions undoubtedly contributed to Russian failures early in the war.

A year on and mud is again constricting Russian action. And it may be that the emphasis that Russia is placing on Bakhmut has more to do with its convenience from a logistical perspective than its material value to either side.

Given the state of the ground, it is not surprising that Russia is struggling to supply much of its front line, with massing resources and troops for an assault impossible along much of its 600-mile length.

Accordingly, Russian forces are focusing on the points they can reach and realistically assault. Bakhmut is relatively accessible from the Russian perspective, being reasonably close to railheads and accessible by road. It is one of the few places along the front line that Russia can effectively supply in inclement weather, which is why it has been under attack throughout the winter and now into the spring.

Logistics in Bakhmut

Modern combat operations are hungry, requiring vast amounts of resources to sustain. For every soldier on the front line, there should be several providing support, moving supplies and fulfilling other vital services.

Russia’s military has always struggled with logistics, due in part to its relatively narrow “tooth-to-tail” ratio. This means it has fewer support staff serving its combat troops than, say, the US military, which can make it hard to keep frontline soldiers supplied.

[Read more: The cities of Ukraine]

Critically, Russia lacks the capacity to sustain operations at any real distance from its depots and rail networks. Its limited inventory of supply vehicles struggles to replenish ammunition, food and fuel at the rates they are expended. When the going is bad, these constraints become even more pronounced.

The Russian problem with logistics, compounded by both an icy winter and now a spring thaw, forces them into repetitive and predictable patterns. There are few places along the front line where Russia can move enough resources to attack. Bakhmut is one of them. It is not good to be predictable – as the reported casualty ratio of one defender to seven attackers makes fairly clear.

Unhappy camp

While Bakhmut is within the reach of Russian forces, it doesn’t mean the logistics problem is solved. Wagner Group forces have been leading the offensive in the region and taking devastating losses.

These forces are even worse equipped and supported than the average Russian conscript, with commanders taking to social media to complain about the lack of equipment and munitions. Indeed, there have been reports that some units are close to mutiny – not just frontline troops, but across senior levels of the military as well.

Clearly, this supply challenge may have less to do with the rasputitsa, and more to do with Russian internal politics. Conventional Russian forces and Wagner Group do not get on. The competition between the military hierarchy and Yevgeny Prigozhin, the Wagner Group’s influential leader, may be the case behind the lack of support.

For their part, the Wagner private army is seemingly willing to sacrifice as many lives as necessary to secure victory in Bakhmut, perhaps seeking to demonstrate their value by scratching out a rare Russian success.

Whatever the reason behind the Russian fixation with Bakhmut, the struggle is taking on a symbolic value for Ukraine as well. After consulting with his top generals, the Ukrainian president, Volodymyr Zelensky, has ordered more troops to reinforce those desperately holding out in the city.

Whatever happens in Bakhmut, with the end of the rasputitsa comes the main campaigning season. By late April, both sides will seek to take advantage of warmer, dryer conditions, possibly leading to rapid changes in territory across the breadth of the front line. This is where Ukraine will need to have the advantage of the sophisticated armour promised by its western allies.

This article by Christopher Morris, teaching fellow, School of Strategy, Marketing and Innovation, University of Portsmouth, is republished from The Conversation.