With Liverpool, it was cotton. For Bristol, it was sugar; for Glasgow, it was tobacco. Then there’s London which, aside from being a hub for shipping, also developed many of the financial instruments that allowed the slave trade to operate. It’s a grim fact that many of Britain’s most progressive cities were built on the profits of the Atlantic slave trade.

The evidence of all this has been fully visible – in statues and plaques, and in the names of streets and buildings – without ever being truly accounted for. As with so much of Britain’s imperial history, this issue has rarely troubled mainstream politics, even as it defines the country in the eyes of the world.

The closest the idea of decolonisation has come to bothering that mainstream was in 2015, when the Rhodes Must Fall movement, which protested the commemoration of Cecil Rhodes and his record in southern Africa, spread from the University of Cape Town to Oxford. But that was reported largely as a matter of campus politics, of wokeness gone mad, rather than one of Britain’s history of racism. What’s more, five years later, the statue at Oriel College that the Oxford students were protesting still stands.

This week, though, something seems to have shifted. On Sunday night, attendees at a Black Lives Matter protest in Bristol pulled down a statue of slaver Edward Colston that had stood in the city centre since 1895. Colston, who lived from 1636 to 1721, was a major local philanthropist who did much to shape the city, endowing almshouses and churches, hospitals and schools. But he made his money through the Royal African Company, which is estimated to have transported over 84,000 African men, women and children to the Americas. The BLM protestors threw his statue into the harbour.

The incident has been criticised by some, mostly on the political right, as a symptom of mob rule: Remove the statue, they say, but not like this. Such critiques ignore the fact that, as Labour’s shadow foreign secretary Lisa Nandy said Wednesday night, “For 20 years, protesters and campaigners had used every democratic lever at their disposal, petitions, meetings, protests, trying to get elected politicians to act. And they couldn’t reach a consensus and they couldn’t get anything done”. The mob got it done.

The protest seems to have opened the floodgates, in Bristol and beyond. The city council has pulled the Colston statue out of the harbour, but the mayor Marvin Rees said it would be moved to a museum, where it can be displayed alongside information about the slave trade and placards from the BLM protest, to put Colston in context. Meanwhile, the city’s Colston Hall music venue has removed all its signage and committed to changing its name by the autumn.

Elsewhere, on Monday, the east London borough of Tower Hamlets removed a statue of another slave trader, Robert Milligan, from its site on West India Quay; the same day, the city’s mayor, Sadiq Khan, unveiled a commission to review and improve the diversity of London’s public landmarks. Plymouth is to rename a square named after another slave trader, John Hawkins. Bournemouth, Poole & Christchurch is removing a statue of scouts founder Robert Baden-Powell, a racist and Nazi sympathiser, from its place on Poole Harbour.

More contentiously, the University of Liverpool is to rename Gladstone Halls, named for the 19th century Prime Minister William Gladstone, whose father John had been one of the largest slaveholders in the West Indies. Gladstone himself, however, was not. The city’s mayor, Joe Anderson, is also resisting pressure to rename Penny Lane – the one from the Beatles song – on the grounds that it’s not named after a slavetrader at all. The matter is contested, but for what it’s worth, the city’s International Slavery Museum thinks he’s wrong.

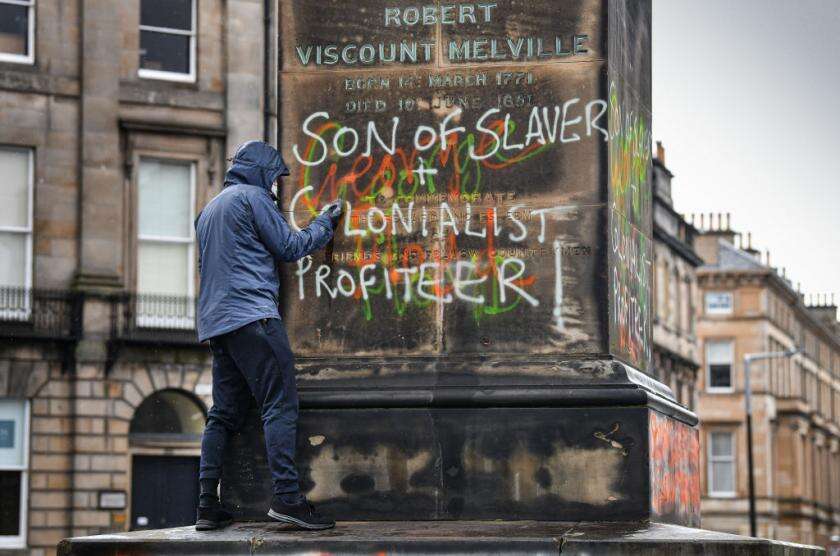

Even if he’s right, there are plenty of other streets in the city that were named after such men. The same is true of Glasgow, where the Green Brigade protest group has been replacing street names with new ones commemorating people like Rosa Parks and George Floyd. The Stop Trump Coalition – which, despite its name, is a British pressure group – has even launched the crowdsourced “Topple the Racists” website, to highlight “statues and monuments in the UK that celebrate slavery and racism” and call for them to be renamed.

The right’s other critique of this movement is that it amounts to rewriting history. But it’s very far from clear that a monument without context teaches history. (Surely a museum would be better?) It’s also not clear why, when everything else about the fabric and identity of our cities is continuously in flux, they are required to leave any statue, let alone one of a racist who treated other human beings as property, in its place forever. As historian David Olusoga argued in the Guardian this week, “The toppling of Edward Colston’s statue is not an attack on history. It is history.”

Oxford’s Rhodes Must Fall protest has restarted, incidentally. Perhaps, this time, he will.