In the middle of April, New York-based software developer Climate Alpha launched a new website that prices the impact of climate change into the future value of more than 100 million homes in the US.

It forecasts financial gains or losses due to climate change between now and 2040 for its users. It claims that 64% of homeowners cite climate change as a reason to move from their current communities, while 62% say they are reluctant to move somewhere because of climate risks.

The pitch is that, for the first time, homebuyers and sellers can see and compare the true price of ownership once climate is factored in.

It is a quiet recognition that the property sector is waking up to the issues of climate change, but while undeniably useful, the industry appears to be talking around the subject rather than engaging with sustainability itself.

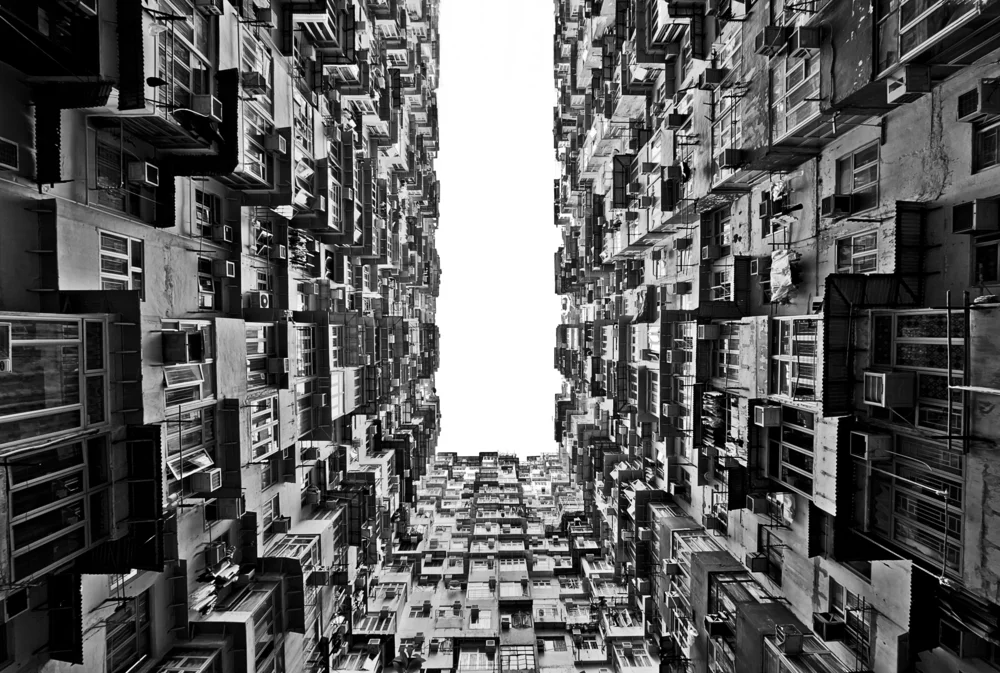

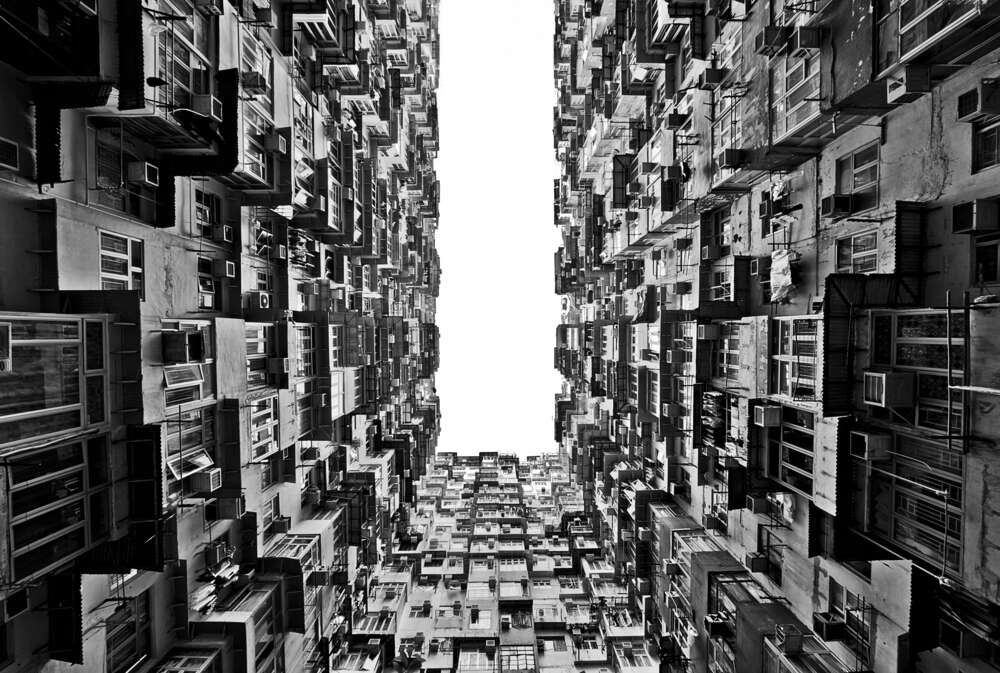

Real estate has one of the highest carbon footprints of any sector. According to the UN Environmental Programme, it produces around 30% of the world’s annual greenhouse gas emissions and, on top of that, consumes nearly 40% of the world’s energy.

There are forward thinkers like French real estate investment trust Gecina, which turned its €5.6bn of debt green in 2021, or Hong Kong’s New World Development which last year sold the world’s first combined green and social corporate bond to tackle emissions and provide affordable housing. Yet it remains an issue that is skirted around more than anything else.

No silver bullet

There is a sense the sector has recognised it needs to move quicker.

“We must and we can halve the emissions in the built environment by 2030,” said Roland Hunziker, director of the built environment at the World Business Council for Sustainable Development (WBCSD), ahead of the real estate conference MIPIM in Cannes earlier this month. He was launching a call to action with global sustainable development consultancy Arup in mid-March.

The report makes it clear that there is no silver bullet for the industry. However, says Chris Carroll, building engineering director at Arup, it is possible to “at least halve embodied carbon emissions in construction now”. The construction industry needs to better use what is already available.

The report calls for the introduction of whole-life carbon measurement as standard practice within the industry. The highest level of reuse is needed, with the industry having to limit life cycle replacement, reuse materials and adopt products with the lowest carbon. In what will be a mind shift for the industry, decisions during the design, planning and investment, including value engineering, should be made on the basis of carbon as cost.

“Companies must quickly gain the confidence to treat carbon like money, setting clear budgetary targets,” the report makes clear.

While all of this is good news, there is a quiet sense of panic within the sector. Moves are being driven by expectations that a raft of legislation is about to hit the industry, chief of which in Europe is Brussels’ current review of the Energy Performance of Buildings Directive (EPBD). “The recast of the EPBD is a crucial element of the [EU’s] Climate Law policy,” noted Marine Leleux, sector strategist for financials at ING in Amsterdam.

The unpalatable truth, she says, is that roughly 75% of the building stock, which is considered inefficient, must be renovated in the next 25 years.

Real estate not excluded yet

It will be difficult to do so. Concrete is central to building and, as a report in mid-April from Sustainable Fitch pointed out, not only is the manufacturing process of cement highly carbon intensive, the industry is responsible for around 8% of global emissions.

More to the point, it is expected to grow. The Inevitable Policy Response (IPR), a climate transition forecasting consortium commissioned by the PRI, expected global cement production to grow by just under 10% by 2050. “For the transition to a low-carbon economy, decarbonising the cement sector will be key,” the Sustainable Fitch report says.

The industry is also being hit by its own raft of legislation. In the EU, cement production is covered by the emissions trading system while the US Inflation Reduction Act contains significant incentives for the cement sector to invest in clean technologies and decarbonise.

Court cases are looking up too. In February, four inhabitants of the Indonesian island of Pari submitted a legal complaint to a Swiss court against Swiss-French multinational Holcim, which they claim is doing “too little” to cut carbon emissions.

The report does not believe that the industry is doing enough. It points out that most companies that have set emissions reduction targets have published medium-term targets for 2030 and long-term targets for 2050.

To achieve the goals of the Paris Agreement to keep global warming below 1.5°C, it says absolute emissions reductions need to occur this decade. The lack of short-term targets within the next two to five years suggests the cement industry has “not yet fully grasped the immediacy of the challenge the transition to a low-carbon future is posing to its industry,” it said.

Significant investment is needed, though green bonds of any flavour remain rare among cement producers.

“The cement sector is widely considered to be one of the most hard-to-abate sectors and its path toward decarbonisation requires significant technological innovation and operational improvement,” says Kathrin Wartmann, associate director of climate research at Sustainable Fitch in London.

Holcim sold a couple of bonds last year – in January and June – while Germany’s HeidelbergCement sold its first sustainability-linked bond in January 2023. In all cases, targets were tied to greenhouse gas emissions reduction targets or emissions intensity targets.

What stands in the sector’s favour is that it is not yet a pariah like oil or coal. The HeidelbergCement 3.75% €750m ($825m) long nine-year bond, for example, saw 4.5 times investor demand.

As the report points out, unlike the financing of fossil fuel companies and projects, “cement companies are not facing any specific exclusion policies from investors”. Those firms that can present a credible transition plan could “unlock significant financing”.

This article originally appeared on our sister site Capital Monitor.