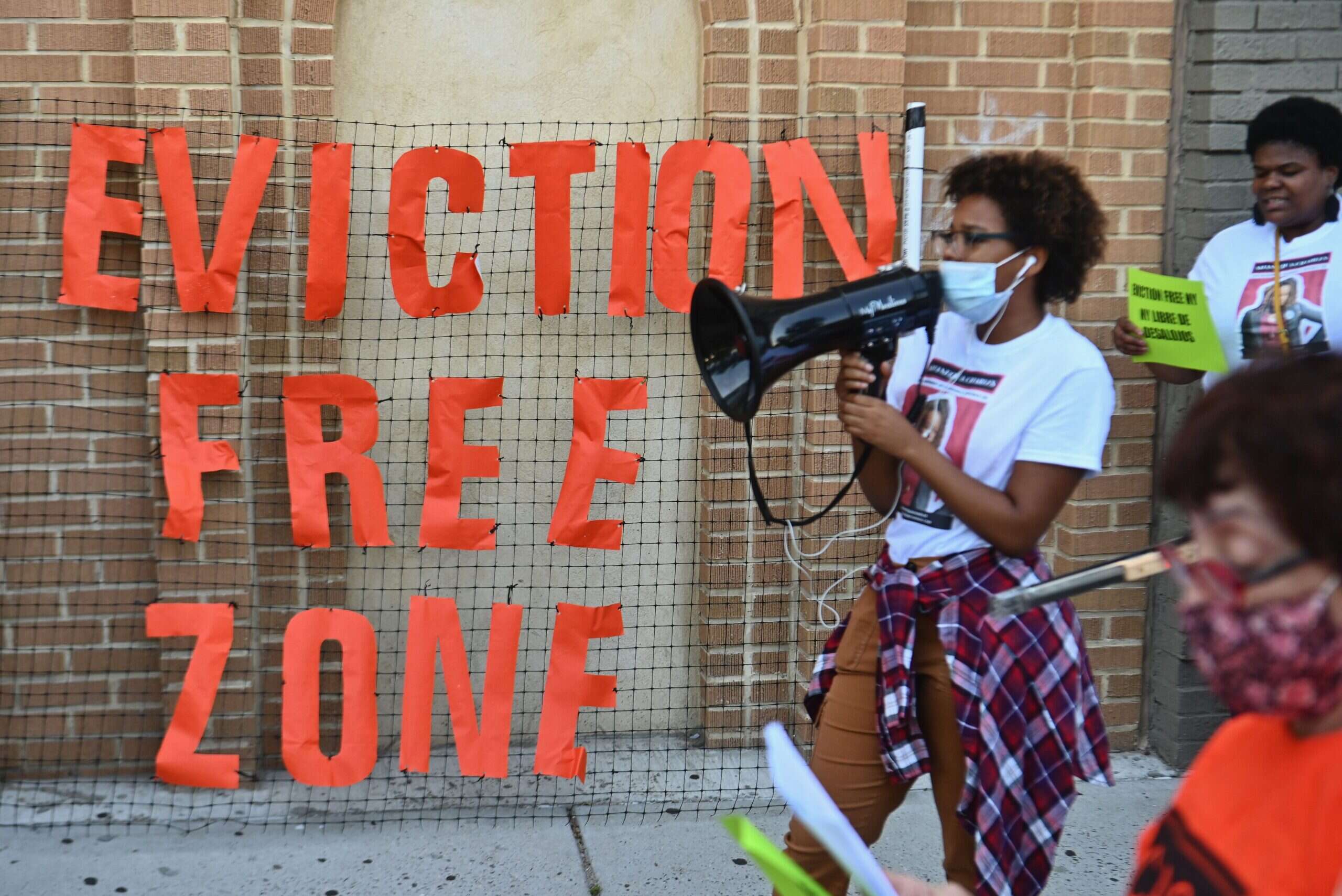

Uncertainty surrounding evictions in the US continues, with many asking if mediation could be the answer. According to NPR and Houston Public Media, the US Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) ruling has done little to curb evictions in the Houston, Texas, area.

A combination of tenants’ not knowing their rights and judges’ not asking whether tenants know their rights under the new order has led to “business as usual” with regard to evictions. The majority of eviction filings in Houston are still being carried out.

Ambiguity and a lack of federal guidance on housing security make the decisions of local leaders all the more crucial right now. Even eviction moratoriums are just another way of kicking the can down the road. Some cities are taking extra steps to provide longer-term solutions to the housing crisis Covid-19 exacerbated.

Cities such as Pittsburgh and Philadelphia in Pennsylvania; Richmond and Norfolk in Virginia; Grand Rapids, Michigan; and Hayward, California, have been developing and implementing eviction mediation and diversion programmes to help renters not only avoid evictions but to remove them entirely from the hazardous eviction filing system.

What is eviction mediation?

Eviction mediation is a process by which landlords and tenants try to come to a mutually agreed-upon alternative to eviction with the help of a trained, neutral mediator.

There are many ways mediation can be incorporated into an eviction process – it can be initiated after or before eviction filings have been submitted, as a mandatory or optional step in the process – but all mediation networks have the end goal of diverting evictions and improving communication between landlord and tenant. Most are crafted with the aim of providing long-lasting assistance to renters and landlords.

Housing mediation programmes have succeeded in the past. In the wake of the 2007–08 financial crisis, then-Judge Annette Rizzo, who at the time was a First Judicial District judge in Philadelphia, established the Residential Mortgage Foreclosure Diversion Program to bring together homeowners, lenders, attorneys and housing counsellors to keep residents in their homes and develop reproducible methods of mediation and diversion that could be used in other places.

The system started in 2008, and it still helps thousands of Philadelphia homeowners each year. Rizzo now works as a mediator for JAMS, a dispute resolution organisation.

What does eviction mediation look like?

Bay Area

Landlord-tenant conciliation strategies are not a novel concept. Palo Alto, California, has had a mediation programme for nearly 30 years, though evictions are not its primary focus. According to Eviction Lab, Palo Alto recorded just eight evictions in 2016, the most recent year for which complete data is available. Rents in Palo Alto are some of the highest in the US. Many of the cases the mediation network sees are related to rent increases. According to Zillow data, the average monthly rent for a two-bedroom apartment in Palo Alto was $3,948 in January of 2020.

Project Sentinel, a California-based nonprofit mediation organisation, manages Palo Alto’s mediation programme. It also manages rent initiatives in Hayward, California, a city just east of San Francisco, and in Mountain View, California, where Google is based.

Before Covid-19, Project Sentinel’s work in Hayward and Mountain View consisted mostly of managing the rent control system in place in each city. But once the pandemic hit, the cities’ focus turned to evictions. Hayward in particular requested mediation services from Sentinel to help the city comply with a wide range of sudden eviction bans.

“There are state moratoriums, there are local moratoriums, there are court moratoriums. There’s just a stack of moratoriums in place,” says Martin Eichner, former director of dispute resolution and housing counselling programmes at Sentinel.

Sentinel helped the city develop the City of Hayward Rent Crisis Mediation Program, which established a system where once a landlord files an eviction petition, a mediator is assigned to the case within 48 hours. Mediators then attempt to find intermediate solutions to overdue payments so that rent isn’t just piling up while moratoriums are in place. Mediators also revisit cases over time.

In addition to facilitating agreements between landlords and tenants, the programme provides tenants with substantial help with documentation and paperwork. To receive protection from eviction, tenants must fill out paperwork stating that they can’t pay rent due to the impacts of Covid-19.

Eichner says that many tenants either don’t know that they need this or don’t have the ability to complete the paperwork on their own.

“So sometimes we wind up helping them at least fill out the form, and that in turn leads the landlord to realise that it really is a crisis. Because believe it or not, the landlords tend to not believe that the tenants are really suffering.”

Philadelphia

Philadelphia had a mediation system before JAMS stepped up to offer pro bono help. The city started the network in the fall of 2019 in partnership with Good Shepard, a Philadelphia-based mediation nonprofit.

Apart from her work with JAMS, Rizzo helped the City Council develop the Emergency Housing Protection Act, which was adopted on 18 June. Among other renter protections, the act established an eviction diversion programme, mandating that landlords and tenants must enter mediation before proceeding with evictions.

Unlike the Residential Mortgage Foreclosure Diversion Program, which helps homeowners once the foreclosure process has already begun, the eviction diversion system intercedes before any official eviction filings can take place. This is a crucial point, as eviction filings, even those that do not turn into eviction orders, can follow a tenant for life, making future housing searches and applications much harder.

Once the act was passed, Rizzo saw the potential benefit she and her colleagues at JAMS could add to the diversion programme. And not only in Philadelphia. JAMS is a worldwide organisation with over 400 mediators in 28 locations. While “locations” may seem less relevant in the remote-oriented world of Covid-19 (most of JAMS’s mediation work is now being done over videoconferencing), the benefit comes from having mediators with extensive knowledge of city-specific policies and resources.

“I call it all the gardens,” says Rizzo. “Everyone has to attend to their own garden, because the walls are different, right? The hope is, with this construct we’re doing in Philly, that [mediators] take it to their locale, work with their local court system, their local city officials, county officials, and start to pollinate this and get a national programme together.”

Pittsburgh

JAMS isn’t the only organisation pooling local resources with an eye toward larger, nationwide solutions. The National League of Cities (NLC) has also established a pilot eviction mediation plan. In partnership with the Stanford Legal Design Lab, the NLC programme offers guidance and resources to cities that already have landlord-tenant mediation systems.

The NLC apparatus doesn’t provide mediators the way the JAMS and Sentinel networks do. Instead, they offer participating cities access to housing experts, guidance on how to efficiently and effectively use available resources, and an environment to share ideas and pressure points with each other.

“This month, we’re doing sustainable funding,” says Lauren Lowery, manager for the NLC’s eviction mediation programme. “Knowing that the CARES Act will eventually run out, how can we set these cities up to begin looking at other federal resources, looking at general fund dollars, looking at the philanthropic dollars to create a sustainable funding source and to continue carrying out their eviction strategies?”

The programme started in early March 2020 at the NLC’s annual Congressional City Conference, not more than a week before many cities initiated Covid-related stay-at-home orders. Representatives from the plan’s pilot cities gathered to talk about what they were doing to curb evictions, what their pain points were in that work and what the goals of the NLC eviction mediation network should be.

Pittsburgh, Philadelphia, Norfolk, Richmond and Grand Rapids are all cities participating in the pilot plan, which runs through December.

Megan Stanley, executive director of the Pittsburgh Commission on Human Relations, says that being able to hear what other cities were doing, how other cities were succeeding and struggling, was extremely valuable in developing a city-specific eviction mediation programme.

“[Philadelphia was] talking about how a lot of tenants were really interested, but they realised that they needed more landlord engagement because both parties have to be willing to go [to mediation],” she says. “And in the end, a landlord always has a lot of power in saying yes to this.”

Stanley says that hearing the representatives from Philadelphia talk about how, in hindsight, they should have done more at the start to get landlords on board with the eviction mediation programme they developed substantially influenced how Pittsburgh developed its own.

“So one of the first things that we did was get a large landlord in Pittsburgh on board with the idea [of mediation], and they really became sort of like the mediation ambassador to other landlords,” says Stanley.

When Pittsburgh began developing its system in March, it had little funding. Through a partnership with the Mediation Council of Western Pennsylvania, the network was able to get 25 volunteer mediators on board to handle up to 100 cases per year.

Since then, through various federal and local foundation grants and with the guidance provided by the NLC system, the Pittsburgh eviction mediation plan has grown to include 49 mediators who receive stipends for each case they take on and three full-time staff members to direct and lead the programme.

Part of the funding Pittsburgh received went toward training community members to become mediators.

“The pool of those original mediators, I’ll be honest with you, was not terribly diverse,” says Stanley. “And there certainly weren’t many people with lived experience or representing communities of colour.”

Stanley sees the programme’s ability to offer mediation training to community members living in places where evictions and housing insecurities are happening as a great asset.

“We thought it was really important to make sure that we had that voice in the programme,” Stanley says. “To understand: What does eviction do to somebody? How does that impact them into the future? So we’re not just treating this like a business transaction but a human-centred issue.”

Since the statewide eviction moratorium in Pennsylvania ended on 31 August 2020, eviction filings in Pittsburgh have gone up 52%, compared with numbers from September 2016.

Richmond, Virginia, another NLC pilot city, had the worst 2016 eviction rate of metros we analysed in our recent US Housing Security Index. Once moratoriums were in place in the city, evictions were down from past averages, according to Eviction Lab data. However, Richmond’s moratorium ended 7 September 2020. Already, September eviction filings are up 260% when compared with 2016 numbers.

The struggle to communicate

Funding will likely always be one of the biggest hurdles between localities and eviction mediation and diversion plans. But just as important is getting the word out that the networks exist and that they’re there to serve residents.

Rizzo, Eichner and Stanley all voiced this struggle when talking about the various mediation programmes they’re involved with. And that work is especially hard when you’re trying to reach at-risk residents before they become officially involved in the eviction cycle.

Rizzo says that during the worst of the foreclosure crisis, the Residential Mortgage Foreclosure Diversion Program engaged neighbourhood action committees to physically knock on the doors of residents who had been filed against to make sure they knew about the network.

“We had so much drill-down outreach. We had notices in utility bills. We had Mayor Nutter (at that time) on billboards, and on the back of buses to say, ‘Call the hotline if you’re in distress.’ We had PSAs. There was an onslaught of across-the-board media to get the word out, to get homeowners ‘under the hood’, get them in the process and link them with a housing counsellor.”

As cities across the US struggle to fund even the most basic city services due to Covid’s decimation of tax revenues, Rizzo worries that the same outreach won’t be possible with the eviction diversion programmes.

There have been, however, small amounts of money available through the CARES Act for such needs. Apart from its work with the eviction mediation network, the Pittsburgh Commission on Human Relations secured $23,375 in CARES Act money to assist in education and outreach for its fair-housing system.

No matter how much help cities offer, evictions will still occur. No city is going to be able to eliminate evictions completely with mediation programmes. But through them, cities can develop longer-term solutions to housing insecurity.

[Read more: Youth homelessness reaches record levels in the UK]