City and state governments in the US are in trouble.

The Covid-19 pandemic sent revenues plummeting this spring, and the $2.2bn CARES Act provided state and local aid only for programmes directly tied to pandemic response efforts. A fiscal crisis is still looming, and with President Donald Trump rejecting another stimulus until at least after the November 3 elections, it’s worth asking what policymakers can do beyond deep and indiscriminate budget cuts.

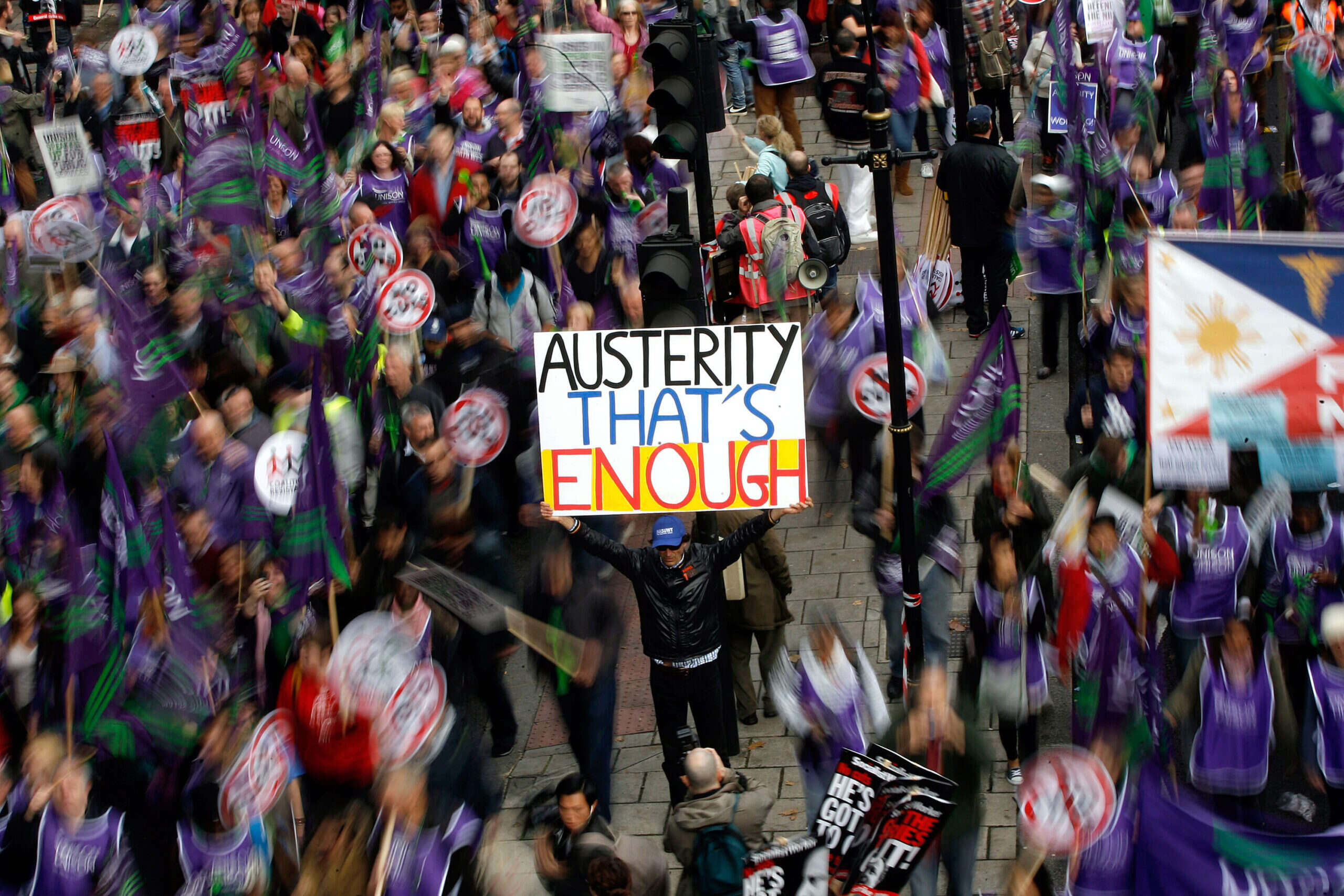

Some economic experts argue that in a time of true emergency, with residents needing public services more than ever, governments have room for alternatives to austerity. Along with targeted cuts and tax hikes, local and state governments have reason to consider borrowing strategies that in normal times would be dismissed as irresponsible.

“We want more federal aid, but we shouldn’t let decision-makers at the state and local level off the hook,” says JW Mason, assistant professor of economics at the City University of New York’s John Jay College. “Local governments have the hardest time raising taxes, but they still have a scope of action. If a state or local official committed to doing everything they can to avoid cutting services, they could find ways of doing that.”

The US’s experience during the Great Recession offers plenty of warnings against repeating this approach during the pandemic. Austerity at lower levels of government undermined the federal government’s stimulus while also weakening and prolonging the national recovery. And that could very well happen again.

How balanced-budget requirements constrain governments

Under the US federal system, states enjoy a much greater degree of independence than regional governments in many other wealthy nations. But they can’t print money and often have balanced-budget requirements, limitations that make it difficult to operate at a deficit, which the federal government routinely does. Governments at the city and county levels are even more constrained.

All of these lower echelons of US government are generally conservative about borrowing. They regularly run deficits for capital projects, issuing bonds for new recreation centres, schools or transportation infrastructure. Projects like these are understood as legitimate targets for state and local debt spending because capital projects are too expensive to pay for upfront and because they take many years to complete. That means future generations cover the tab for the project, but they will also get to use it. Borrowing to pay for operating spending, however, transfers the costs of current government functioning to future residents and is considered verboten.

There are historical reasons for this. In the turmoil of the Great Depression, many states adopted balanced-budget requirements. During the late 20th century, US cities faced fiscal crises as a result of capital flight and the suburbanisation of the middle class. States like Colorado and Texas dealt with unique crises, like regional booms and busts around energy prices, and tweaked their tax and spending restrictions accordingly. Governments were disciplined by the bond markets and national politicians for spending beyond their rapidly diminishing means. Many state and local policymakers remember the lessons of those decades well and are risk-averse when it comes to budgetary matters.

“We have to have a balanced budget. You can’t spend more than you have,” former Philadelphia Mayor Michael Nutter said at a September online Urban Institute event. “Fiscal discipline is critically important. If you start removing or tinkering with those rules, you will find cities literally going bankrupt, going out of business… I think that is potentially the worst self-inflicted wound.”

But experts like Mason argue that the situation is more complicated than Nutter makes it out to be. Small cities or the most historically depressed urban centres, like Detroit, will have less room for manoeuvre. But at the state level, and in some big cities, they say this time could be different.

How to work around balanced-budget requirements

Many cities and state leaders talk about balanced-budget requirements as ironclad rules. But there is actually some flexibility to them.

Vermont is the only state without a balanced-budget rule, but the details of the restriction vary across the other 49 states. Although there are no actual legal penalties to running deficits, many states in the South, Midwest and Great Plains have clearly and strongly worded balanced-budget requirements.

But in most Northeastern states, including New Jersey, the stringency of the requirement is up for interpretation. Because localities are creatures of their state governments, these rules often apply to city and county budgets, as well.

That’s why when New Jersey passed its budget at the end of September, policymakers plugged its budget hole by borrowing $4.5bn for operating expenses and increasing taxes on millionaires and corporations. There were still cuts – $1bn of them – but the overwhelming majority of the shortfall is filled with deficit spending, not austerity measures.

Although New Jersey’s Democratic governor, Phil Murphy, faced backlash and a lawsuit from Republicans, he was able to win in both the legislature and the courts. New York City Mayor Bill de Blasio is the only other major local or state leader to make such an aggressive proposal, and he has met with less success so far: when he first suggested borrowing to pay for operating expenses earlier in the pandemic, he received harsh criticism from Governor Andrew Cuomo and a scolding editorial from the New York Times.

While no other governments have yet considered anything like the scope of New Jersey’s new budget or de Blasio’s proposal, there is some evidence that there could be room for such borrowing – especially if Democrats sweep the November elections and a substantial relief package becomes possible.

“Some states, like Georgia and Colorado, are really straitjacketed to the point that they can’t do much,” says Skanda Amarnath, director of research and analysis at Employ America. “But it’s a spectrum, and a lot of states, including California, are not exploring this as much as they should. The biggest challenge is political will to work around legislative or constitutional constraints.”

Typically, states and cities borrow a bit over the course of the year through short-term bonds or direct loans to meet current expenses. Tax revenue does not always arrive exactly when it’s needed, so policymakers borrow a little one month to meet immediate expenses and pay it back when, say, annual property tax revenues arrive.

During the pandemic, as revenues have become far more volatile, this kind of lending has increased as cities and states borrow to maintain services in the hope that federal aid arrives or the economy bounces back.

For their part, banks have been willing to backstop cities and states in greater amounts than at any time in the past decade.

This summer, direct lending saw its largest quarterly growth since 2012. (Bond issuance jumped too, although less radically.) Unlike in normal times, lenders aren’t expecting it to be paid back at the end of the fiscal year, either. There’s no sign that lenders are moving to cut off state and local governments. Rates have not gone up, which is a sign that there is not a supply constraint and that credit ratings would not take a hit in the short term. (Both de Blasio’s proposal and New Jersey’s budget faced political opposition, but they were not rejected by the markets.)

“Normally, behaviours like borrowing for operations are bad no matter what part of the credit cycle you’re in,” says Matt Fabian, a partner at Municipal Market Analytics. “But we’re outside the credit cycle right now. This isn’t about a weak economy; this is about the pandemic. Investors and rating agencies are a lot more tolerant.”

Different approaches to borrowing

Balanced-budget requirements relate only to operating expenses. Almost all states use debt to finance capital spending, which could be used to good stimulative effect right now. One University of Massachusetts study found that infrastructure spending creates 9.8 jobs per $1m spent. With the cost of borrowing at an all-time low, this could be the ideal moment to purchase new transit vehicles, for example, or remove asbestos from historic school buildings.

“It makes total sense to engage in countercyclical spending with capital projects,” says Amanda Page-Hoongrajok, assistant professor of economics and finance at Saint Peter’s University. But she says that bigger projects – like a new transit line or a big housing complex – take years to get designed and permitted. That means to get real stimulative effect out of municipal and state spending, it should be targeted at repairs or smaller-scale projects that can be started right away.

“You would want to get the spending going immediately. Brand-new construction, especially on a super-big project, bureaucratically is going to take much longer,” Page-Hoongrajok says.

States can also borrow from themselves by putting off payments to other government entities. In some ways, that could backfire: if a state government cuts back on aid to cities, that will only push job cuts and service reductions downstream.

But other payments could be deferred that don’t have direct impacts on the national recovery. State governments all maintain an array of trust funds, which can be deferred up to a point. State and local pension trust fund payments, for example, do nothing to fight a recession right now. Those allocations for future retirees can be deferred to a time when the economy isn’t suffering through a historic crisis.

In some states that have especially acute pension crises, like Illinois, that idea could be a trickier sell. But there are other deferments and self-borrowing that could be used too.

“In California, they deferred certain payments to school districts and asked the school districts to borrow to fill the gap,” says Tracy Gordon, senior fellow with the Urban-Brookings Tax Policy Center. “It’s a very safe form of borrowing because they basically can say to creditors, ‘We’re expecting this payment from the state, but it’s just delayed.’ Creditors usually say, ‘Yes, we get that – it’s fine.”

If governments do decide to go the austerity route, experts say there are more-targeted and less damaging ways to raise taxes and reduce costs.

After the Great Recession, state and local policymakers filled 45% of their budget holes through spending cuts and only 15% through tax increases, in part because many kinds of taxes would take money from the households that are most likely to spend their incomes in ways that will juice the economy. The wealthy, however, save most of their income or spend heavily on financial assets that do little to contribute to output. In an emergency, when stimulus is needed in the short term, taxing lower- and middle-income people will take demand out of the economy. Taxing the rich, or capital gains, will not have such a depressive influence.

When it comes to cuts, targeted spending reductions are healthier than slashing departments across the board, which demoralises and incapacitates vast swaths of the government. In 2013, the National Association of State Budget Officers put together a report about what worked and what didn’t in response to the Great Recession. One of its highlights was that across-the-board cuts were fast and easy but too blunt of an instrument.

“They often evoke criticisms because across-the-board cuts do not facilitate priority setting or encourage agencies to deliver recommendations on ways to save money,” the report reads. “Furthermore, across-the-board budget cuts reduce critical services even as demand is increasing.”

Similarly, cuts should be avoided for the programs that both employ the most people and provide essential services. For example, as more people work and learn from home, generating large accumulations of recycling and garbage, now would be a terrible time to cut sanitation services.

The Great Recession didn’t spur a great deal of innovation in local policymaking, but that doesn’t mean this crisis won’t. At the federal level, even in the absence of a second stimulus package, lawmakers in many ways have already acted far beyond what they contemplated in 2009.

A similar story is unfolding in Europe (despite recent hitches). A few state governments, like New Jersey’s, are taking bold action by borrowing to avoid austerity, and raising taxes on the rich and corporations. Cities like Austin are making targeted cuts to their police departments in the face of calls for reform, while de Blasio has at least considered raising operating funding from bond issuance.

“It’s a very conservative culture where the municipal and state leaders seem to feel that borrowing money is some terrible crime if you don’t do it in exactly the right way,” says Mason. “I think borrowing money to fund the government feels almost sinful to them. But in a crisis, you could maybe challenge that.”