Transport infrastructure and land use patterns form the backbone of a city. It’s the reason so many people choose to live and work with other people in cities – despite the noise, congestion and negatives of city life – because they can easily reach a variety of destinations. Towards this objective, many planning agencies set themselves a “30-minute city” goal, which is behind many planning decisions.

What did the study find?

The ease of reaching destinations can be measured by the number of jobs reachable within 30 minutes. Job locations offer both employment opportunities and amenities; restaurants, schools, hospitals, shopping centres and so on are also job clusters.

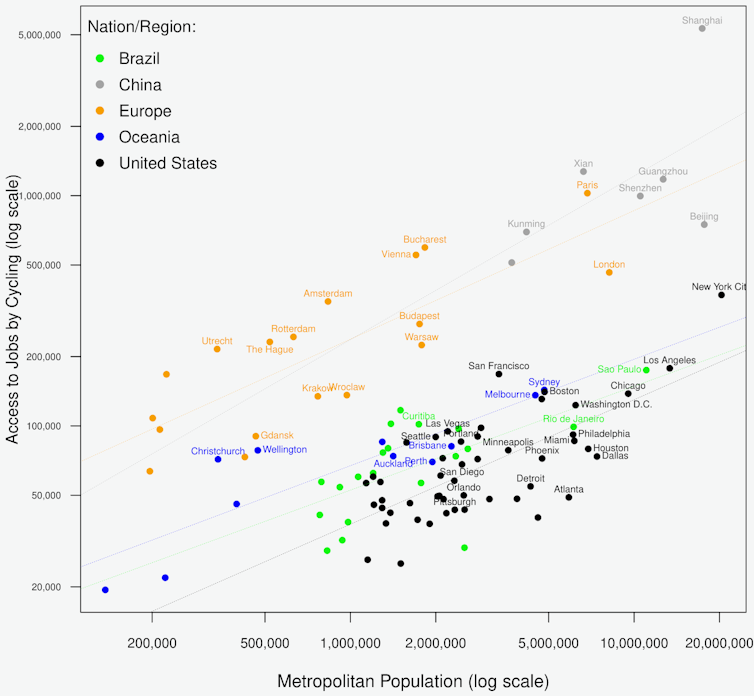

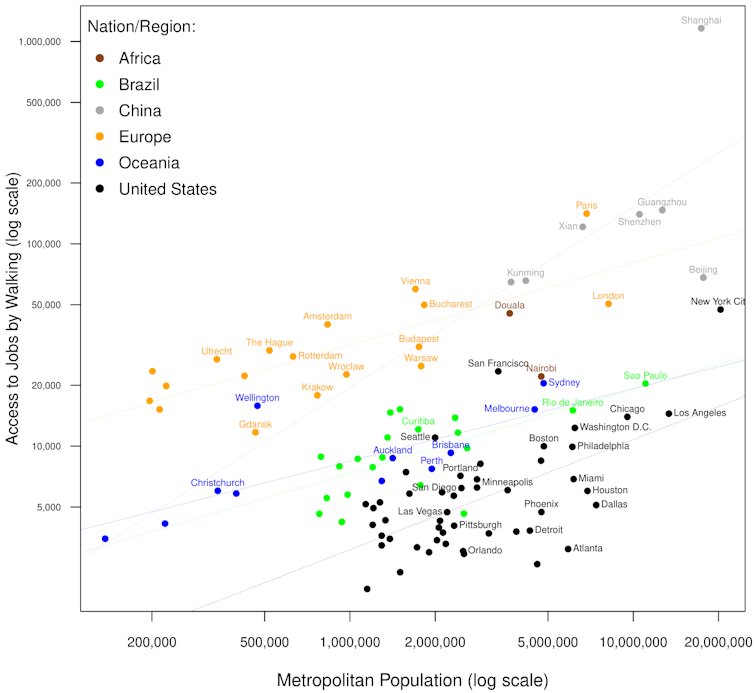

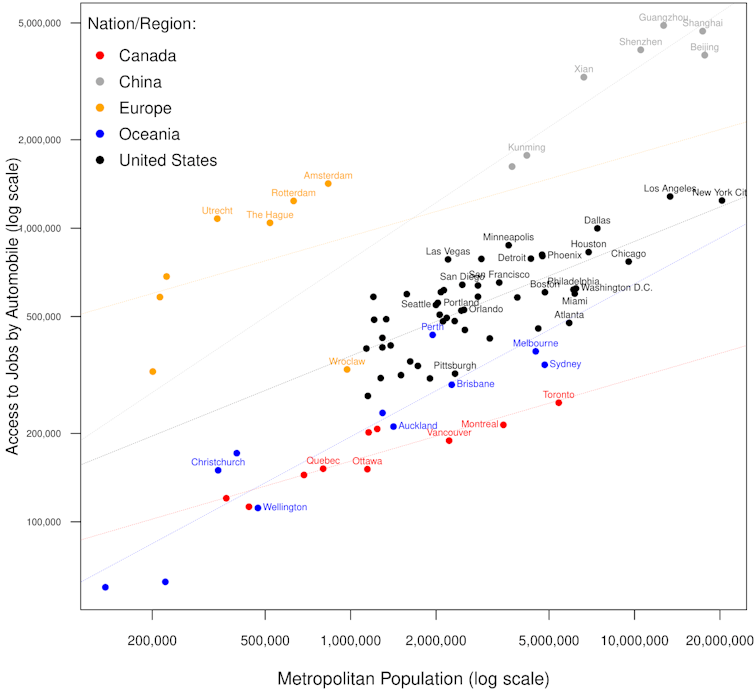

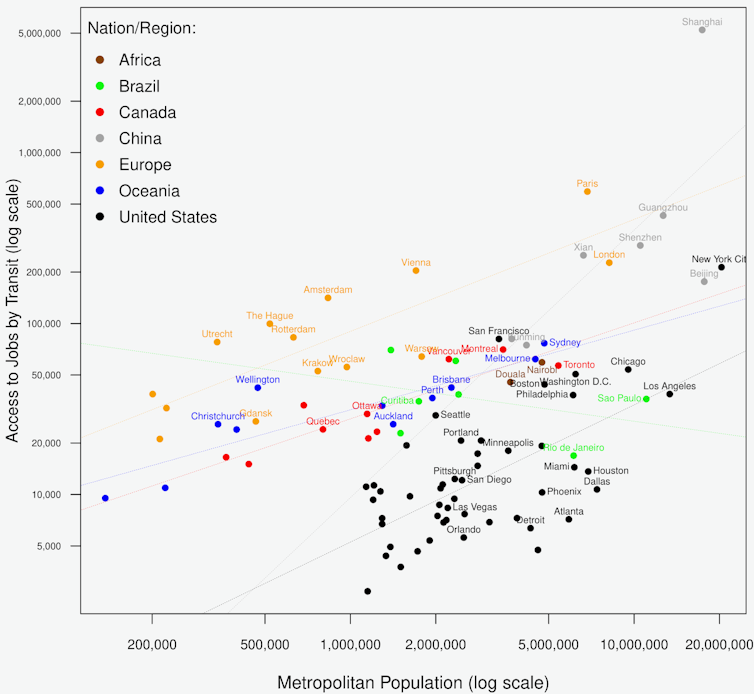

The research measured how many jobs were accessible within 30 minutes (travelling one way) for four different modes of transport – cars, public transport, cycling and walking. The 117 cities studied are in 16 countries on six continents. The research finds cities really differ in the convenience of transport, but also finds significant similarities between cities from the same country.

Australian and Canadian cities have poorer car access than US, European and Chinese cities. They have better public transport, walking and cycling access than US cities, but access via these modes is generally not as good as in Europe and China.

Cities in the US have reasonable car access, but lag behind globally in public transport, walking and cycling access.

In Chinese and European cities, compact development combined with an intensive network produces the highest access globally across all modes of transport.

One surprising finding is the middling car access in US cities. Despite the reputation of US cities being built around the car, urban sprawl has made it difficult to reach destinations, even by car.

This sprawl also exposes the Achilles heel in mass transit and non-motorised modes. Immense spatial separation makes for worse access by public transport and active modes of transport such as cycling and walking. US cities have the largest disparity between public transport and car travel.

This research also finds access to jobs increases with city population, so reaching a greater number of desired destinations would be easier for people in larger cities than in smaller cities. So, despite traffic congestion, larger cities are still more efficient in connecting people with places they want to go.

However, this benefit has diminishing returns. Doubling the metropolitan population results in less than a doubling of access to jobs.

What are the lessons for Australian cities?

The moral of the story is that we don’t need to choose between the US-style sprawling development and European-style compact cities. We can and should have the benefits of both development patterns. We need both density and a well-developed transport network for better access.

Massive road building alone can improve access by car to only a limited extent. The problem is that investments in road infrastructure are often accompanied by lower-density development. That makes it harder for people who walk, bike or use public transport to reach increasingly separated places.

In cities that do have compact land use patterns, access to jobs remains high across all modes of transport, including cars. So, despite congestion, it is still easier to reach desired destinations in these compact cities. Roads are not race tracks, and high-speed roadways connecting nobody with nowhere are not better than lower-speed paths connecting people and places.

The Australian government is investing A$110bn over the next ten years in transport infrastructure. This will have significant implications for the future of our cities. If we want our cities to continue to be vibrant, liveable and accessible by all modes of transport, we will need to keep our cities compact and invest more in public transport, walking and biking.

The newly published research finds access to jobs increases with population and that the two largest Australian cities, Sydney and Melbourne, compare favourably with similarly sized cities overseas.

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.