Messaging on climate change is everywhere in Singapore, from adverts for green banking products to explanations from workers in the hawker markets about the switch from plastic to balsa wood forks. One reason Singaporean society seems so alert to the issue is that it is very much on the environmental front line: 70% of the country lies only 15m – and 30% less than 5m – above sea level.

Such climate awareness is fitting because action is badly needed, according to Berlin-based Climate Action Tracker. The non-profit organisation rates Singapore’s climate targets and policies as “critically insufficient” and its policies and action as “highly insufficient” in terms of their alignment with the 2015 Paris Agreement.

The government is making the right noises. Singapore is among the few countries to have imposed a carbon tax, aims to make its large petrochemical industry more sustainable, and is touting itself as a natural climate-technology hub.

Sitting down to speak with Capital Monitor, Grace Fu, minister for sustainability and the environment since July 2020, shows she is aware of the challenges at hand. The overarching direction for what she is trying to do is set by the Green Plan 2030, an ambitious initiative launched in February last year to drive Singapore’s national agenda on sustainable development en route to its net-zero 2050 target.

Petrochemicals: the “elephant in the room”

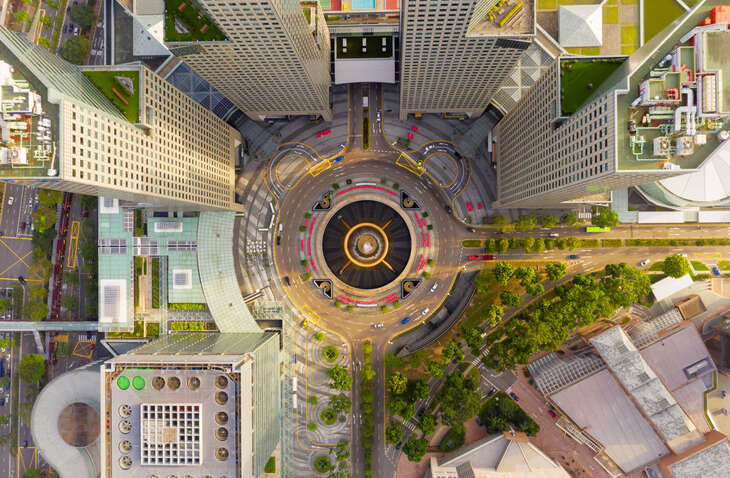

However, the “big elephant in the room” is Jurong Island, an area of reclaimed land south-west of Singapore created in the mid-1990s, Fu says. It is the heart of the country’s petrochemical industry and employs some 27,000 people, with 100 companies running operations there.

As a result, Singapore is now the ninth-largest exporter of chemicals in the world, according to the most recent World Trade Statistical Review from the World Trade Organisation. Its oil refining industry can produce 1.5 million barrels a day, making the city state the world’s fourth-largest exporter of refined petroleum in 2020 (the most recently available figures), behind the US, Russia and the Netherlands.

“We recognise the value [this] adds to the economy in terms of jobs and so on, but we are not happy with the status quo and want to see changes,” Fu says.

In a paper published in October last year, National University of Singapore researchers estimated that Jurong Island was responsible for 27 million tonnes of carbon dioxide in 2019, 54% of Singapore’s total CO2 that year.

Fu's solution is to shift the production focus towards natural gas – recently and controversially labelled as a transition (and thus ‘sustainable’) fuel by the EU Taxonomy – and attract investment in speciality chemicals for renewable batteries. The initiative began in November last year, with the Agency for Science, Technology and Research, the Economic Development Board (EDB), and JTC Corporation – part of the ministry of trade and industry – looking into technologies and the EDB helping to support companies.

[Read more: A Singaporean firm has become the go-to master planner for African cities]

Fu says she has set up a platform to help facilitate such investments and is “cajoling” industries to come together. “We are looking at ways for people to come together and have a beer on Friday night to get those conversations going,” she says.

Indeed the government has developed a plan to turn Singapore into a greener and more sustainable city by 2030. It sets a target that the city state must by then increase the output of sustainable products by 1.5 times from 2019 levels, ensure its refineries are in the top quartile of the world in terms of energy efficiency, and facilitate two million tonnes of carbon capture.

The government is using carrots and a stick to try to achieve these goals.

Fu says the government has signalled that it will use its procurement budget to help changes happen and hopes that the government can be a catalyst to drive down costs with the adoption of new technology.

Carbon tax: "an effective lever"

The stick that Singapore is using is its carbon tax. It was the first country in Southeast Asia to introduce such a regime, in January 2019, and has only (partly) been joined in the region by China. The latter launched a carbon trading market in mid-July last year that gives companies financial incentives to cut their emissions.

The carbon tax is an effective lever, says Fu, because “it’s the best signal to the industries about the explicit costs of carbon emissions”.

Set at S$5 ($3.59) per tonne of carbon dioxide from 2019 to 2023, the minister of finance, Lawrence Wong, said in this year’s budget in March the carbon tax will be raised to S$25 in 2024, then S$45 in 2026, and would hit S$50-S$80 per tonne by the end of the decade.

As is the case with such taxes elsewhere, though, those figures are still well below the $75 recommended by the IMF as needed to incentivise achieving net zero by 2050 and what the UN Global Compact ($100) had said should be in place by 2020.

Still, Singapore is one of the few markets to have such a regime in place. The tax is mandatory for all businesses that produce more than 25,000 tonnes of emissions a year. In practice, that means the country’s 50 largest emitters in the oil refinery and power generation sectors as well as the waste and water sectors. The government says it covers 80% of Singapore’s total greenhouse gas emissions

“We have openly said that our carbon tax is not a revenue-generating policy; rather, it’s a signal to the industry to start planning early,” says Fu.

The government brought in S$197.9m from carbon tax last year and forecasts the same amount for this year. Revenues raised will be used to support decarbonisation efforts and the transition to a green economy, and to cushion the impact of the transition on businesses and households.

Fu acknowledges concerns about carbon tax arbitrage – where companies move to other jurisdictions to avoid such levies – and admits that Singapore businesses might find themselves penalised on top of the already high costs of land and labour.

But this will be a short-term problem, she argues, as more countries will have to impose carbon taxes for climate action to be effective globally. In the meantime, the government is maintaining dialogue with industries about their transition plans and how it can help, Fu says.

Climate technology focus

On a related note, she sees the country’s small size as an advantage in its push for sustainability, in that it can catalyse new technology much faster than larger nations through integration between technology, policy, finance and markets and the ability to work with the private sector “anywhere along the chain”.

“Singapore has that ability to synthesise ideas and offer ourselves as a classroom for observation,” she says.

That said, Fu is cautious about being seen as a regional leader for Southeast Asia, despite the city state effectively playing that role when it comes to financial markets.

“What works in Singapore may not work in the region as well because we all have very different circumstances and we are at different levels of discussions about climate action,” she says.

Fu admits that the Covid pandemic as well as broader geopolitical tensions since then had introduced some friction to climate discussions with Singapore’s neighbours, but she made no mention of the war in Ukraine and any impact or implications.

At the Nikkei's Future of Asia conference in May, Malaysian prime minister Ismail Sabri Yaakob bemoaned the “negative ripple effect” from the war in Ukraine and tensions between China and the US on regional cooperation as countries turned inwards.

But now that international travel is resuming, Fu expects greater collaboration and visits to re-establish ties with the likes of Indonesia, Malaysia and Thailand.

Geopolitical headwinds

With the Cop27 climate summit coming up in November in Egypt, Fu feels the momentum for climate action is not now as strong as it was last year, thanks to economic headwinds as well as the knock-on effect on energy supplies amid Russia's invasion of Ukraine.

Fu did not mention the implications of the Ukraine crisis for Singapore specifically. But in 2020 – the last published figures – Russia exported $1.1bn worth of petroleum oils and oils from bituminous products (but no crude oil), to Singapore, and Russian imports in total made up $1.4bn (0.42%) of Singapore's imports. Singaporean exports to Russia were even smaller, totalling only $548m in 2020. The city-state has since 5 March banned the export of weapons to Russia and blocked Russian banks, but not the import of oil products. The ministry of trade and industry could not immediately provide comment on whether it would ban trade of oil and oil products with Russia.

In respect of Cop27, Fu expects there to be “long and heated discussions” about climate change mitigation targets, but also that there will be movement towards harmonisation of climate reporting standards.

Addressing global warming seems to have fallen down the priority list in the UK, US and even arguably continental Europe (vis-à-vis the inclusion of natural gas in the taxonomy of sustainable activities), even as Britain and parts of America smashed temperature records this week.

Fu’s outlook does not sound hugely optimistic, but it may be the best one can hope for.

This article originally appeared on Capital Monitor.