During the Covid-19-caused lockdowns, many of us relied on nearby green spaces for exercise and mental respite from the stress of the pandemic. A Natural England survey found that 89% of respondents agreed that natural spaces are good for mental health and 40% said that nature, wildlife, and local green spaces were even more important to their well-being when restrictions were in place. With a third of adults continuing to work permanently or partly from home, the need for green space remains pressing.

Access to such spaces has long been an issue for those in urban settings where people are less likely to have private outdoor space. In London, one in five households have no access to a private or shared garden and, for those who do, these gardens are 26% smaller than the national average. While a high proportion of urban residents live near public green spaces, there is growing evidence that certain groups, including women, older people, disabled people and ethnic minorities are more likely to experience barriers to access due to lack of facilities, cultural norms and perceptions of safety.

[Read more: Why urban green space needs to do more to serve diverse communities]

Alongside access issues, local parks increasingly lack the maintenance required to make them safe and welcoming spaces. Between 2013 and 2021, the proportion of parks nationally reported to be in ”good condition” by park managers slipped from 60% to just over 40%. This decline has almost certainly been exacerbated by the high use of parks during the pandemic but is underpinned by the erosion of local authority funding in an age of government-imposed austerity.

Despite there being a proven return of £27 for every £1 spent on local parks in terms of health, well-being and the environment in London, for example, over half of local park managers expect there to be further budget reductions over the next five years.

New ways to provide green space

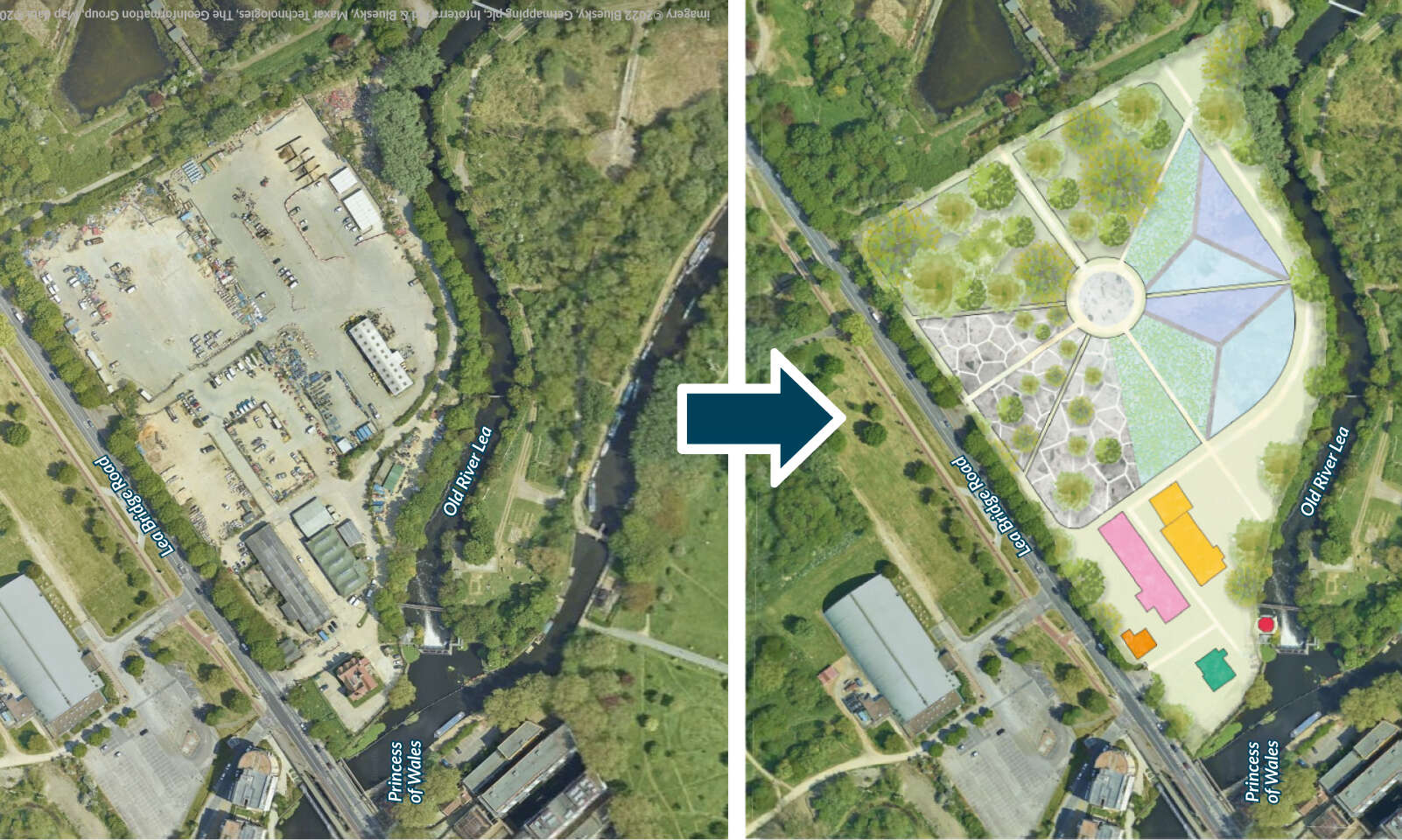

In the face of this, communities have risen to the challenge of providing green space in bold and creative ways. This is the case for the East London Water Works Park, which aims to buy an industrial site on the Waltham Forest and Hackney border and transform it into a biodiverse community-owned park. The site is currently owned by the Secretary of State for Levelling Up, Housing and Communities, which has had planning permission for two free schools rejected.

Based on this, the group believes that the only possible future for the site is as a park, where they plan to transform the old Victorian filter beds into swimming ponds and establish community spaces and a forest school.

The ponds, which are planned to be as big as two Olympic-sized swimming pools, would have historical significance as the newest natural swimming ponds in London since the Hampstead Heath ponds were opened in 1777. They would also be the only community-owned ones. An estimated 1,200 people per day would be able to take advantage of the physical and mental health benefits of wild swimming for free, in water cleaned naturally by reeds and aquatic plants.

With a focus on sustainability and decarbonisation, the site is also intended to operate as a circular economy and generate its own renewable energy from solar power and hydropower. The ultimate vision for the park is to offer people a new way to experience nature, with the hope that birds, squirrels, bees and many other animals and insects that are vital to our ecosystems will thrive in the brownfield rainforest.

As well as being a calm and meditative space, the park would bring people together through organised recreational groups, volunteering initiatives or informal meet-ups. A nationwide study by the Office of National Statistics (ONS) found that nearly one in three Londoners felt lonely for some or all of the time during the pandemic, which is 20% more than the England-wide average. The group hopes that having a welcoming and safe space for groups of people to share interests and activities will provide individual purpose and strengthen community spirit and support.

[Read more: 60 years later, Dallas seeks to right a past wrong]

To address barriers to access, the team is leveraging their local knowledge and connections to engage with groups who are typically underrepresented in projects like this. They hope that strong community leadership will ensure that this is a development done for people, not for people. They are currently crowdfunding to raise £1m with the hope that they will be able to secure a further £2m through corporate donations and grant funding to purchase the land.

Considerations have also been made for the practical upkeep of the green space, with a plan to use a group of volunteers for maintenance and to operate income-generating aspects, such as a café, as social enterprises. If successful, this means the park will avoid a long-term dependency on continued grants and crowdfunding. If the necessary funds are raised by the end of this year, the timeline would see construction begin in 2025 and the site open to visitors in 2029.

Increase green space with parklets and beyond

The concept of reclaiming and rewilding dead urban sites to green space is not confined to large-scale projects. Across the UK and Europe, the “parklet” movement is gaining momentum, with individuals and small groups identifying small areas on their streets to transform into pockets of green for passers-by to enjoy. Such spaces are vulnerable to vandalism and opposition from councils, but this hasn’t deterred residents from maintaining their parklets and even lobbying local authorities to recognise and protect them.

The creation of biodiverse space in urban settings was even celebrated at RHS Chelsea Flower Show this year, when Jason Williams won a silver gilt medal for his entry “The Cirrus Garden”, a design based on his verdant 18th-floor balcony garden in Manchester.

The pandemic has played a large role in changing widespread views of accessible green space from a perceived luxury to a basic right, which has galvanised urban residents into practical action. Ideally, community groups shouldn’t be responsible for creating and protecting green spaces.

Still, they are well placed to do so due to their local knowledge, relationships and awareness of accessibility issues. By channelling their collective creativity into these projects, communities are making a powerful statement about the value of green space, which must surely be followed by the support and investment of local authorities and government.