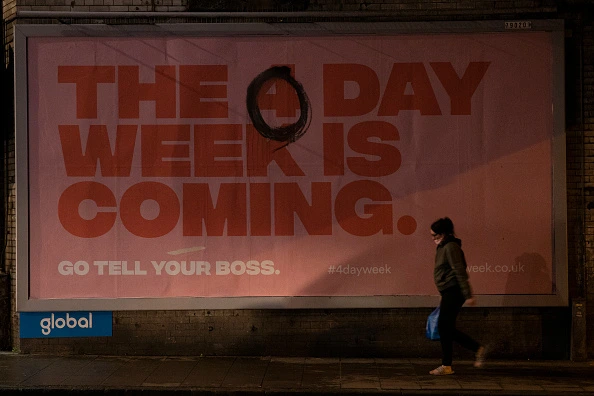

Every few years, the four-day working week makes its way into the news cycle and becomes a matter of public debate. The subject re-emerged again in 2023 with the conclusion of the world’s largest public trial in the UK, which boasted 92% of employers keeping the new working arrangement.

The pilot has garnered widespread positive news coverage, but could this actually mark a new step in British labour standards?

The road to the four-day week

The adoption of the four-day working week will inevitably draw comparisons to the development of our current five-day system, which came about through very similar arguments as those had today.

While Sunday had long been a day of rest and godliness, along with the ‘Saint Monday’ day off in some industries, the standard working week was usually Monday to Saturday throughout the 19th century. Pressure groups and trade unions made strides to introduce half-day Saturdays – purely at business owners’ discretion – and finally, by 1934, Boots had closed factories on Saturdays and Sundays.

The thinking was that a two-day weekend would reduce redundancies among staff, who were creating surplus products, but it also had the benefit of reducing illness and absenteeism in the workforce.

Those same claims have re-emerged nearly a century later with the four-day week campaign, which argues that British workers will be less stressed and more productive working fewer hours for the same pay, leading to a happier, better-retained workforce while reducing costs for employers.

Even before looking at the four-day week, the working hours-productivity disconnect is borne out in data. Despite the gains made over the decades, analysis by the TUC show that the UK has some of the longest average working hours in Europe at 42 per week, 1.8 above the EU-27 average, and sees hourly productivity well below comparable EU economies.

The four-day week trial and city workers

While the idea is floated every few years or so, the pilot conducted from June to December 2022 has attracted more attention than any before, at least in the UK press.

That’s partly due to the scale – 61 companies participated – but also because of its overwhelming success. Of those 61, 56 are continuing with the change and 18 have confirmed that it is permanent.

Under the pilot, employees kept 100% of their pay with a “meaningful” reduction in work. This led to a 39% reduction in stressed employees, 71% less burnout and a 73% increase in life satisfaction, all with 35% higher revenues between the trial period and the previous six months.

Intuitively, workers in cities would appear to be the primary beneficiaries of this kind of development. After all, it is simpler to chop one day off the weekly office 9–5 with pay intact than it is to balance shift work on a 32-hour rota.

And while the make-up of the pilot reflected that balance of professions, it was not restricted to industries associated with city workers and a variety of working patterns were implemented.

Businesses operating in healthcare, arts, manufacturing, construction and engineering took up 29% of those in the trial, and while their success rate is not broken down in the total, the 92% overall continued adoption rate means by definition that these industries must have also seen overwhelmingly positive results.

Perceptions of the four-day week

While the latest data is unequivocal in its findings, the wider picture is less absolute.

According to YouGov polling from 2019, the professional world is generally in favour of the change, with 64% of businesspeople backing it. Moreover, 74% of Britons responded that they can complete five days’ worth of work in four, while 71% thought one fewer working day would make the nation happier and 45% believed a four-day week would be more productive – the highest in Europe.

The support is not a recent phenomenon, either. Nearly a decade ago, in April 2014, similar YouGov polling showed that 57% of the public supported the introduction of a four-day week.

However, the subject has had a much harder time in the political arena. The 2019 Labour manifesto pledged to “reduce average full-time weekly working hours to 32 across the economy, with no loss of pay, funded by productivity increases” within a decade, which became one of many controversies in the failed campaign.

More recently, in a parliamentary debate in October 2022, Conservative MP Sir Christopher Chope described the prospect of a bill to reduce weekly maximum working hours to 32 as a “hand grenade thrown into the economy”.

How likely is it?

Specifically in statutory terms, a four-day week – 32 hours – seems an unlikely prospect. That is for the reason that typical working weeks already fall well below the legal maximum, which is 48 rather than 40. The dim view taken by the current political establishment does little to alleviate this.

But in reality, the five-day week was not led by parliament either. The working hours the UK has come to expect developed from grassroots support, trade union pressure and trial by a major company.

Modern employers are evidence that we could be on the cusp of change again. According to Natwest's 2022 recruitment report, almost half (48%) of employers expect the four-day week to become the norm by 2026 and four in five (78%) believe it will by 2030. In keeping with previous surveys, these employers are also broadly convinced of the benefits, but 60% do not offer the option because they are not prepared or unsure of their capacity to implement it.

Studies like those published by Autonomy and the Four-Day Week campaign may then be key to ushering in the future norm by demonstrating how employers in different industries can make the new arrangements work at scale. But while the conditions now reflect the last reduction in working hours, the same outcome is far from assured.

[Read more: Hidden unemployment: England’s northern cities significantly higher than official figures]