In the past 100 years, cities have seen an increase in crises, pandemics and economic pressures – but not all are hit equally.

Large global cities are much more insulated from economic change than small cities. Places relying on only one main industry are more vulnerable than diversified economies, and those with once-robust tourism and travel economies are often hit the hardest.

Place branding (how we picture places in our imagination and what makes places notable) is complex, much more complex than singer Jason Collett’s flippant lyrics “if you can tweet something brilliant, you’ve got a marketing plan.”

A place’s brand is its overall image that’s constantly in the making. Its brand is being established through every photo, comment and tweet.

Place brand transformations can be documented in real time, as seen through social media. Throughout the pandemic, we can see that place brands have evolved and those likely to survive are the ones that were already well established to begin with or that continue to show differentiation in what they offer.

Branding evolves in times of crisis

During times of crisis, the predominant voice is often tipped too far one way or the other, and the sentiment the place brand message is hoping to convey can take a dramatic turn.

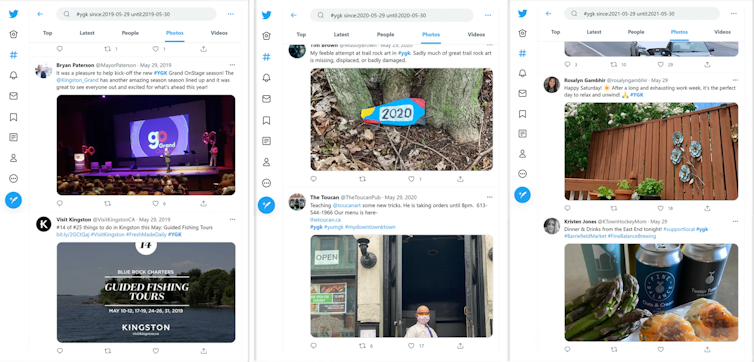

A snapshot in time (pre-Covid) of the Twitter feed for #ygk – a city hashtag for Kingston, Ontario – on 29 May 2019, highlights a balance of waterfront, parks and artistic events shared by both residents and visitors.

On the same day in 2020 and 2021, in the midst of the pandemic, the images shared primarily by residents contributed to a new place brand for the city that focuses on gardens, home offices and take-out. This place brand is not unique to #ygk.

The value of these new symbols and mental souvenirs may prove to have limited long-term value to the post-crisis Kingston brand due to the lack of differentiation.

Off-limits in branding discourse

Economic crises and other categories such as crime, terror, political or natural disasters are considered off-limits in branding discourse. However, the motivation for place branding often depends on or is a built-in response to a crisis.

The Williamsville Neighbourhood Association in Kingston was born out of an anti-growth agenda, but the real neighbourhood place brand was most notably established during the 1998 city-wide ice storm that left many residents without power for several weeks.

In an interview, one local resident noted: “We’ve seen key events that have brought people together that created more feelings of connection. One example is the 1998 ice storm. In our immediate neighbourhood, and I would say a little bit further afield as well, people made connections as we all wandered the streets making sure neighbours had enough food and fuel to burn in the fireplace, seeing neighbours and helping out clearing the downed tree.

“There was a real sense of everybody helping each other to the point where, for the first few years after the ice storm, we’d have a block party every summer to celebrate the coming of spring.”

Several other residents noted the “new, neighbourly feel” that attracted them to move to Williamsville post-ice storm. Without the ice storm, the neighbourhood may have continued to suffer as a run-down industrial place to get your car fixed instead of a vibrant, family-oriented place where potluck dinners became the norm.

Perceptions impact place brands

Place brands such as the romanticism of Paris or the innovation aura of Silicon Valley are slow to develop, but they show remarkable stability and elasticity with an ability to revert to pre-crisis perceptions.

But following a crisis, place brands are much more vulnerable to place brand substitutions — like going to Kelowna for wine tasting versus a trip to Spain — and fragile to stereotypes, made more prevalent through social media platforms.

Place brands, more so than the realities of places themselves, have often faltered due to negative stereotyping or brand imaging.

The 1918 flu didn’t start in Spain, but became a place brand for Spain through media, leaving Spain’s brand image woven into a history of poor public health.

Negative perceptions are major economic obstacles for cities hoping to attract investment and promote tourism. This will perhaps be the same fate for the UK or India, both having Covid-19 variants attributed to them.

The recovery and resilience of cities, and in particular their brands, during major economic events, are highly stratified and individualistic.

Jon Coaffee, urban geographer, helps us understand brand resiliency as “the ability to detect, prevent and, if necessary, handle disruptive challenges.” With that definition of resiliency in mind, local economies have proven that it is possible to be both vulnerable and resilient at the same time.

These complex situations present uncertainty where both unknowns and unpredictability are highly prevalent. Resiliency planning to ensure survival post-crisis relies on lived experience. The only way to overcome this uncertainty is to consider resiliency as performative, that is, city brands are always in the making and striving for sustainability rather than resilience.

The road to recovery is likely through relying on industries with better demand and lower operating costs or through increasing social cohesion such as what has been seen through the #BuyLocal movement over the past year.

Either way, the answer to place brands post-crisis will not be found through advertising. Resiliency will only be built through policy and embracing a place brand that is always in the making – embracing the crisis as part of a new brand story.

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.