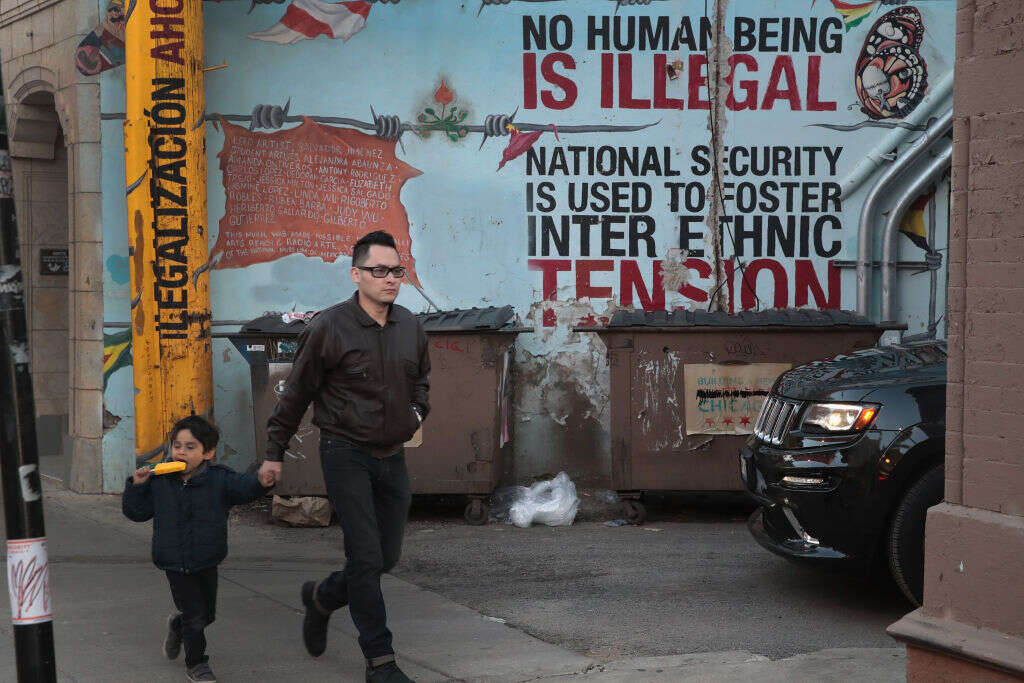

Sanctuary cities have been a frequent villain of Donald Trump’s presidency. In his pursuit of hostile immigration policies, Trump often targeted places that offered measures of protection for their undocumented residents. But in the days before inauguration, President-elect Joe Biden has signalled that he’ll take a dramatically different approach to immigration starting on his first day in office.

Experts interviewed by City Monitor say the Biden administration may offer cities more leeway to adopt local policies that support immigrants and undocumented residents. But challenges remain. A Trumpian strain of anti-immigrant sentiment will likely feature heavily in political opposition at all levels of government, and states in particular still have immense say over what their cities can do. Local governments will continue to face important decisions about their level of cooperation with federal agencies, and those choices will have tangible effects on the lives of all residents, regardless of their citizenship status.

What is a sanctuary city?

While there is no universally agreed-upon definition of “sanctuary city”, the term broadly describes a local jurisdiction with a policy of limiting its involvement in US federal immigration enforcement.

The work of detaining and deporting unauthorised immigrants falls to the federal government. Agencies such as US Immigration and Customs Enforcement (ICE) can ask local law enforcement to help them in this work, and in many places that’s what happens – but crucially, the federal government cannot compel cities to assist them.

Localities decide how and if they lend support. They can use local jails to hold people for ICE, for instance, or allow local police to make arrests on the agency’s behalf. Places that refuse to participate are said to have sanctuary policies. The Immigrant Legal Resource Center, a non-profit immigration organisation, has tracked more than 2,700 counties that have in some way declined to participate in immigration enforcement as of 2019.

What Trump and Biden mean for sanctuary cities

Politicians have long used the sanctuary label as a political cudgel, but Trump escalated the stakes of the fight.

His attacks weren’t just rhetorical: at the start of his presidency, Trump issued an executive order attempting to withhold federal funding from cities if they refused to cooperate with immigration enforcement officials. This resulted in a protracted battle directly between the federal government and cities.

Federal courts repeatedly struck down the executive order as unconstitutional, saying the president had no grounds to withhold funds allocated by Congress. Still, in 2018, the US Department of Justice threatened 23 jurisdictions, including New York City, Los Angeles and Denver, with subpoenas to force them to comply, threatening to withhold grants for law enforcement. The most recent attempt to withhold funding was upheld by a federal court in February 2020. In some places, the threats had their intended effect.

“We saw a lot of places that would have engaged in [sanctuary policies] be intimidated by the Trump administration,” says Lena Graber, senior staff attorney at the Immigrant Legal Resource Center. With a more sympathetic administration coming in, though, that may change. “There’s now room for a lot of those places that felt intimidated by the attacks from the federal government to step up and now say, ‘Okay, now we’re ready.’”

What sanctuary policies look like in practice

Cities have real power to resist being involved in immigration enforcement, Graber says. Some actions are as straightforward as declining to participate in federal initiatives that train local law officers to carry out immigration enforcement. Other options for cities may not explicitly target immigration but have knock-on effects.

For example, a city may not have direct control over its jails, which are usually run by counties in the US. But a city may still prohibit its police force from making arrests based on immigration violations, as is the case in Lansing, Michigan. Even broader still, cities may enact criminal legal reforms that reduce residents’ contact with the justice system in the first place. The Bronx, New York, has a policy of declining to press charges against people arrested for specific misdemeanours, such as fare evasion or driving without a license. For undocumented residents, this can cut off one possible path to deportation.

There are also cities that have addressed areas other than enforcement and put in place affirmative, immigrant-friendly policies. Erie, Pennsylvania, has done this with the help of Welcoming America, a non-profit organisation that provides US cities with resources and guidance to support its immigrant residents.

Over the past year, Erie has undergone the process to become “Certified Welcoming”. The mayor’s office created programmes to help immigrants in various areas of civil life, with efforts to improve language access, establish jobs initiatives and offer cultural competency training.

“It’s a big step for the city of Erie to acknowledge that there is a growing population of refugees and immigrants,” says Niken Astari Carpenter, the city’s new dedicated liaison, who led the Welcoming America certification process. “The mayor sees personally how refugees and immigrants have this entrepreneurial spirit and how they contribute to the community.”

Sanctuary cities in Biden’s immigration platform

Cities hoping to enact more immigrant-friendly measures are likely to have an ally in the Biden administration. The Washington Post reported Tuesday on the incoming president’s intention to overhaul national immigration policy as soon as he takes office. Plans include a path to citizenship for millions of undocumented immigrants and executive orders to expand refugee admissions. For Biden – who in 2007 spoke out against sanctuary cities – these plans represent a move to the left of even the Obama administration.

As part of his agenda for the Latinx community, Biden has also pledged not only to roll back Trump-era agreements involving local immigration enforcement but also to “severely limit” the use of agreements between the Department of Homeland Security and local law enforcement, known as 287(g) agreements. Some have argued that this would effectively create a nationwide sanctuary policy, similar to the legislation California passed in 2017.

Cities are being really cautious right now. Rick Su, University of North Carolina School of Law

The immigration platform that Biden campaigned on also includes a plan to create new visa categories that would allow cities and counties to petition for more immigration to counter the effects of demographic decline.

Accomplishing these lofty plans will first require Biden to reverse Trump’s numerous immigration restrictions. It will be no small task to undo the vast web of executive orders, memos and structural changes crafted by Trump’s immigration adviser, Stephen Miller. In one of the first interviews given on the subject, Biden officials Susan Rice and Jake Sullivan attempted to manage expectations, saying many changes would “take time to put in place”.

State governments may still be the biggest roadblock

Even with federal support, cities will likely face hurdles in enacting policies that support undocumented immigrants. Legal scholars expect that some states will forbid local sanctuary policies and require cities and counties to cooperate with immigration enforcement.

This has already happened in Texas. In 2017, Republican Governor Greg Abbott signed Senate Bill 4, which requires all Texas law enforcement agencies to comply with ICE requests and forbids localities from adopting any policies to the contrary. The law personally penalises any local leaders who would defy the legislation with fines or even jail time.

Alabama and Florida have passed similar laws, and immigration legal scholar Rick Su expects that this trend of state pre-emption will continue to define the issue for some time.

“Cities are being really cautious right now,” says Su, a professor at the University of North Carolina School of Law. “Even if they can enact some of these [sanctuary policies], they’re afraid to attempt it. They don’t want to prompt the bear.”

The city of Austin has still taken what steps it could in spite of SB4. In 2018, the city council passed the “Freedom City” resolutions, one of which asks police to report how local resources have been used in immigration enforcement and to share the data they send to federal immigration agencies. In the realm of reducing contact with the legal system, it has taken measures to reduce arrests and require police to accept multiple forms of identification.

“You have to think creatively outside of what the state has prescribed for localities to do,” Graber says.

Biden’s stated immigration priorities include advocating for states to repeal anti-sanctuary laws, an acknowledgement of the tension between states and cities as well as the federal government’s limited role to get between them.

And that may ultimately be the driving force in sanctuary city policies over the next four years: liberal cities may be gaining an ally in the federal government, but state governments ultimately have more power over cities and tend to be much more conservative. If states decide to stand in the way, they may be able to thwart Biden’s attempts to change procedure at the local level. But where cities are allowed to, they may have their best chance yet to take steps that support their immigrant communities.