The war in Syria has turned many of its cities into battlegrounds. Places like Aleppo, Homs and Raqqa have been reshaped beyond recognition by the destruction of architecture and the mass displacement of citizens.

Residents are trapped in a war zone, struggling to cope with everyday activities. Their daily routines involve checkpoints, security zones and besieged neighbourhoods. They live between ruins and are disoriented within their own homeland. Amid mass destruction, they have lost a sense of belonging in the cities they used to know.

In Syria, where the war has entered its eighth year, architects and urban planners can no longer wait for “post-war reconstruction” plans or “peace resolution”. Instead they are already working to save their heritage, preserve their identity, and protect their history from being erased by extreme violence.

This is happening in a variety of ways. Some are hiding cultural artefacts in secret graveyards to protect them from demolition and looting. Some are trying to rebuild destroyed houses and souks, and provide shelter for internally displaced populations. Some are travelling to other countries – Lebanon, Jordan and Turkey – to receive training on the best ways to save their cities and heritage.

A destroyed neighbourhood in Homs. Image: Author provided.

The war has made it vital for architects to shift their thinking in an attempt to respond to the changing dynamics of war. As part of my own research, I have spoken to Syrian architects based inside and outside the country about how work to rebuild these cities can be supported from afar. Several ideas have emerged, including the creation of mentoring programmes, research collaborations with academics, and providing online learning materials on architecture, construction and project management.

One of the most common themes was the need for resources – on rebuilding, on bringing communities back together – to be published in Arabic. I am now working on a translation project of ten briefing papers from the “Conflict in Cities” project of the Urban Conflicts Research Centre (UCR) at the University of Cambridge with Professor Wendy Pullan.

The Arabic materials will be openly shared in early 2019 with audiences in the Middle East to share knowledge about topics such as urban regeneration, politics of heritage and the role of cities in reducing conflicts.

But we must also remember what any future reconstruction is for. Architects, academics, politicians, economists and developers each have their own agenda and interests. For some, the reconstruction is a financial opportunity to invest and make money. For others it is a place for foreign designers to experiment with new ideas.

There are already fears that the last to participate in these emerging plans and conversations will be the Syrians themselves – and that such plans might not put the Syrians at the heart of the reconstruction.

After all, many of those interested in the “reconstruction” of Syria have little knowledge about the country, the way of life, and its social and cultural landscapes. We must remember that any construction that does take place will be upon land that is soaked with the blood of Syrian men, women and children.

We must also be wary of a lack of balance in the plans for reconstruction and the building of urban resilience – the capacity of the city, its systems and its inhabitants to adapt to different shocks and stresses.

The power of building

In some cities, reconstruction and resilience are only focused on a few spots of the city, and benefit only particular communities. Some disadvantaged communities are overlooked. As the urban design expert Lawrence J. Vale notes, uneven resilience threatens the ability of cities as a whole to function economically, socially and politically.

A ruined residential area in Homs. Image: Author provided.

But there is also hope. Architecture could bring huge positives to a devastated Syrian society. It can be symbolic and powerful when architects have the opportunity to face history, instead of whitewashing it – when architecture can contribute to creating spaces and places for everyone, and not only for the elite.

In his book Building the Post-War World, Professor Nick Bullock explains how after World War II, rebuilding created an opportunity for the spirit of innovation and experimentation linked to the hopes of a new and better world and architecture.

In Syria, with such huge loss of the fabric of cities and countryside, architects are searching for the “Syrianess” of Syrian architecture. Many of the architects I spoke with emphasised the need to build a new Syria, for Syrians, by Syrians.

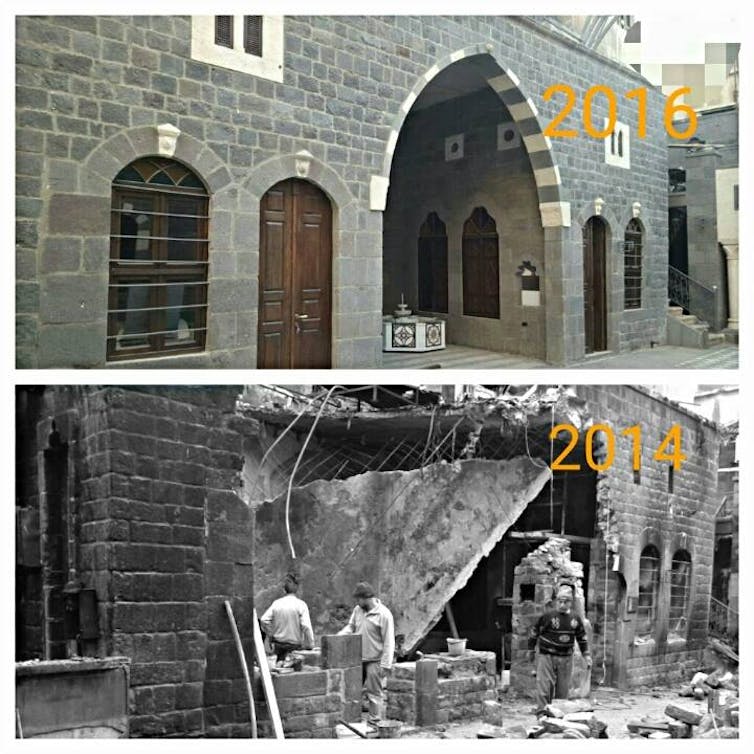

Julia Domna Palace rebuilt in the Old City of Homs. Image: Yvonne M. Al-Abdi/author provided.

They do not want to apply an international architectural language in their cities, or a Beirut-like reconstruction plan that does not reflect the identity of the country. Instead, they are looking towards a Syrian identity through architecture – architecture that can bring a sense of social justice and cohesion to all Syrians. To the displaced, to the poor, and to the disadvantaged – rebuilding a Syria for everyone.

![]()

Ammar Azzouz, Visiting Scholar, University of Cambridge.

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.