The results of the 2020 US presidential election show a widening urban-rural divide in US politics, according to an analysis of preliminary election results by City Monitor.

Heavily urban areas have long been associated with larger shares of Democratic voting, but the results of this year’s election show that this relationship is becoming more extreme, with bigger swings in the vote towards the Democrats tending to occur in more densely populated counties.

By looking at “swing,” we’re analysing the change in the performance of the Democrats, as defined by their vote share, relative to the same metric for the Republicans. This is a method more generally used in multiparty systems such as in the UK but makes sense in the 2020 US presidential election because both major parties saw increases in vote share this year. The vote can swing to a party without that party winning in that area – it is an indicator of progress or regression.

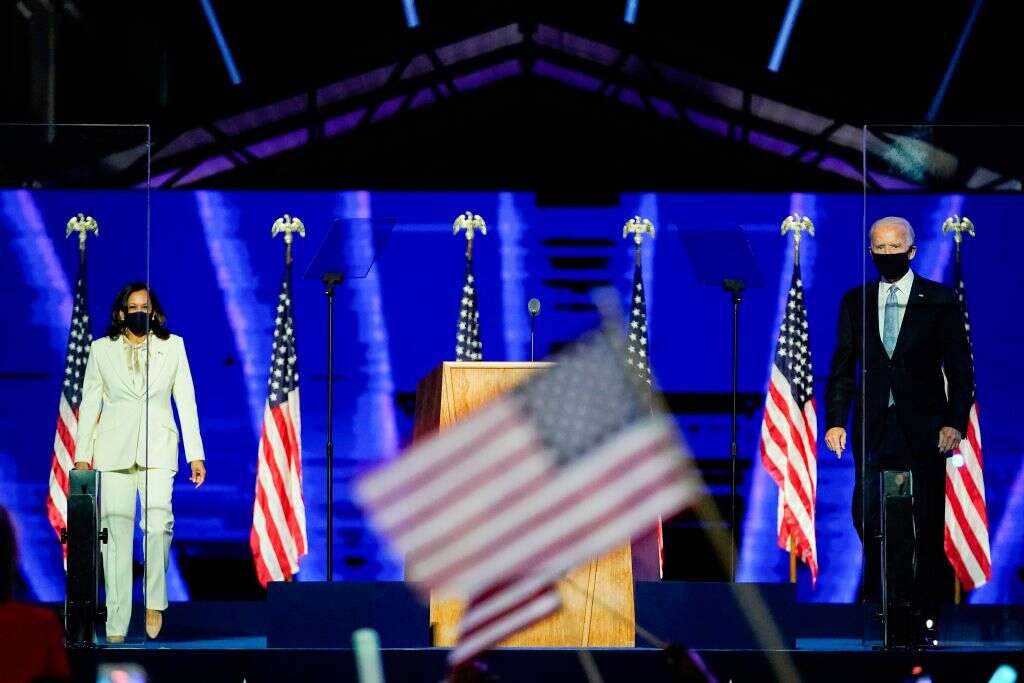

Based on this measure, President-elect Joe Biden saw more favourable margins between his share of the vote and President Donald Trump’s in 47% of counties across the US when compared to the latter’s margins against Hillary Clinton in 2016, according to results data reported by the New York Times.

Break down that data by urban/rural status and a more divided picture emerges.

Throughout this article, we will refer to counties in metropolitan statistical areas, or MSAs, of one million population or more as large metro areas. Counties in MSAs of with between 250,000 and 999,999 people will be called medium metro areas. Counties in MSAs of fewer than 250,000 population will be called small metro areas, and all other counties will be referred to as rural areas.

Trump’s margins worsened in 74% of large metro areas, per our definition above. Included in this group are counties that encompass major cities such as New York County, New York (otherwise known as Manhattan), and Los Angeles County, California, as well as inner- and outer-ring suburban counties such as Collin County, Texas, near Dallas, and Stafford County, Virginia, an exurb outside of Washington, DC. As you travel farther away from densely populated cities, Trump’s margins fared better. In the most rural parts of the US, only 36% of counties saw Trump’s margins get worse compared with 2016 numbers.

These shifts mean the Democrats’ overall lead in large metro areas increased to a margin of 14 percentage points among counties where at least 90% of the expected vote have been counted. This is up from an 11.6-point lead in 2016 and a 0.8-point lead in 2004.

Meanwhile, the vote in midsize and small metro areas also swung to the Democrats after two elections in which they lost ground in these counties. These areas are generally still majority-Republican, but 61% of them saw swings to Biden this election.

It is important to note that while Trump’s margins shifted in many counties, not all of them “turned blue” this year. Of the 1,246 counties that swung to Biden, Trump held on to 79% of them.

It’s possible, however, that this picture could change when the final tallies are in.

Better performance near cities helped Biden flip key states

Even though Biden didn’t flip hundreds of individual counties, based on the data we have so far, movements towards Biden in areas surrounding large cities were crucial in flipping states such as Pennsylvania.

Biden’s home state saw ten of its 13 large metro-area counties, mostly made up of suburban and exurban areas, and 13 of its 14 medium metro counties swing towards Biden, even though Trump still held the edge in some of them. Of course, winning counties doesn’t translate into Electoral College votes, but these multiple small shifts towards Biden are likely to have been a key reason why Pennsylvania turned blue overall.

Many of these medium metro areas are in the eastern part of the state, between Philadelphia and Harrisburg, and include the counties of Lancaster and York, where Biden achieved a quarter more votes than Clinton.

What is interesting in these areas is that the improved performance of the Democrats in Pennsylvania was not obviously achieved by changing the minds of those who voted for Trump in 2016. He achieved more votes compared with four years ago in all 14 of the state’s counties classified as medium metro areas, but all 14 still swung towards Biden.

A similar pattern can be observed in Virginia, another state that Biden flipped. Stafford County, an outer-ring suburban county about 40 miles south of Washington, DC, saw Trump margins shift by 12 points this election when compared with the last one, dropping him low enough to lose, with only 47.5% of the vote to Biden’s 50.8%.

Urban areas moved towards the Democrats in red states, too

This shift towards Biden in medium and small metro areas – driven largely, it seems, by the Democrats’ benefiting more from turnout increases – can also be seen in states that did not turn blue on election night.

For example, Trump won in Collin County, Texas, which contains the northeast corner of Dallas and the city of McKinney. In 2016, Trump won in Collin with 55.6% of the vote. This election, he was able to bring in only 51%.

Again, this change looks to have been driven by greater voter turnout rather than wholesale switching between the two major parties. Those numbers are still preliminary, but compared with the 2016 election, Collin saw nearly 126,000 additional votes, an increase of 35%. The population of the county has also increased by nearly 10% since 2016.

While changes in many small and medium metro areas didn’t result in Biden “flipping” counties, Trump did lose some of those he won in 2016. Tarrant County, Texas, the urban county that is home to Fort Worth, saw Biden sneak by with 49.3% of the vote, compared with Trump’s 49.1%. While experiencing a mere 4% increase in population between 2016 and 2019, Tarrant saw a 24% increase in votes cast this election. As of this writing, the New York Times estimates that 96% of votes have been counted there.

Williamson County, Texas, a suburban county outside of Austin, saw Trump’s margins shift by 11 percentage points, dropping his 48.2% share of the vote just below Biden’s 49.5%.

Is this good news for cities?

It’s tempting to view the fact that a Democrat has won the 2020 presidential election as good news for the political representation of people living in cities; however, there are reasons to be cautious.

City Monitor examined this issue in an interview with Stanford University professor Jonathan Rodden, author of Why Cities Lose, before the election. He highlighted the danger of Democratic politicians’ ignoring the growing polarisation of politics along urban-rural lines in the event that they win the presidency.

The danger for cities is that national politicians do little to address the fact that, electorally, urban voters are at a big disadvantage in the US’s winner-take-all system. The Republican Party won the Electoral College without winning the popular vote in 2016, and it could be argued that a potentially unsustainable level of turnout was one of the main factors that prevented this happening again in 2020.

“A lot of this gets papered over when you have a big blue wave,” explained Rodden. “As the Republican Party has lost support in many suburbs, the entire problem we’ve been talking about may be diminishing. In that case, Democrats might come to the conclusion it’s not a problem at all anymore. Over time, they might be correct in that assessment. As the political geography changes – and it’s really changing quite dramatically – the problem may be going away. Or it might just be going into hibernation for a little while and then it shows up again a few years later.”

This election has shown that urban and rural voters in the US have grown yet further apart when it comes to their political preferences. Neglecting to address this divide through electoral reform now might mean the problem comes back with a vengeance in future elections.