The short-term rental market has ballooned in recent years. According to the Residential Landlords Association, Airbnb listings in ten UK cities increased by almost 200 per cent between 2015 and 2017. And while attention has mainly focused on the problems this is causing in big cities such as London, or tourist hotspots such as Barcelona and Berlin, communities in England’s regional cities are also feeling the effects.

The growth of short-term rentals is closely tied to the broader financialisation of housing – that is, changes in the housing and financial markets, which turn housing into a commodity. These changes have opened the door for new investors to buy and develop more and more units, which in turn increases the scarcity of housing, prompts landlords to raise rent, threatens community bonds and stretches neighbourhood services.

The short-term rental sector is made up of two different business models. Serviced apartments are typically run by a single business, which offer a hotel experience for visitors in many city centres. Landlords can also rent out rooms or entire properties through sharing economy platforms such as Airbnb. By providing this service, Airbnb has given people a new means to earn money on their homes – sometimes without having to follow all the laws that apply to renting.

Growing trends

In 2016, the Association of Serviced Apartment Providers found that 86 per cent of serviced apartment units in Manchester were occupied throughout the year. Alongside other regional cities such as Liverpool and Bristol, Manchester is a key target for serviced apartment operators.

To find out exactly how short-term rentals are affecting regional cities such as Manchester, I undertook research to collect data on 22 serviced apartment schemes, containing 1,198 units across central Manchester and neighbouring Salford during 2017. The average starting price for a night in a serviced apartment was £99, and owners made an average monthly income of £2,563 per unit. The financial rewards of investing in serviced apartments clearly outweigh the returns on long-term rentals for residents, which yield around £850 per month.

Getting trendy: street art and cycles in Manchester’s Northern Quarter. Image: Kylaborg/Flickr/creative commons.

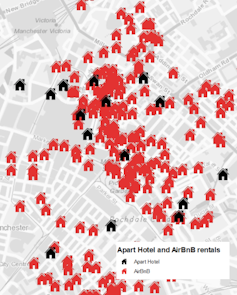

To find out about Airbnb, I used a 2016 survey by sector analysts AirDNA, which showed a total of 310 units advertised on Airbnb within central Manchester, and more than 1,500 across the city region. They noted a 70 per cent annual growth in the sector from the previous year. The average price per night for an entire property is £143, with the highest being £1,251.

Across the city, my research identified 357 properties, which had been taken out of the long-term rental market up to 2016, with many more expected over coming years. Indeed, real estate company Colliers recently reported that in 2017 there were more than 4,000 units being used for short-term rentals, in a city struggling to build affordable housing.

The 2016 data from AirDNA revealed 177 hosts operating Airbnb properties in central Manchester: 59 owned multiple properties and accounted for 62 per cent of all listed units. It is likely that many of these hosts are people who own multiple properties, or who set up small enterprise to use housing in central Manchester as a business.

And there are concerns that those properties taken out of the long-term rental market may not be operating with any licensing or planning permissions. A report by the All-Party Parliamentary Group for Tourism, Leisure and the Hospitality Industry – a group of MPs from Labour, Conservative and Liberal Democrat parties, who meet to discuss issues in the industry – raised concerns that sharing economy platforms do not check if hosts comply with gas and fire safety regulations before they let out their properties.

Neighbourhoods on the frontline

Serviced apartments, concentrated in the Northern Quarter. Image: Jonathan Silver/author provided.

Short-term rentals are clustering at certain locations across Manchester, especially the popular Northern Quarter, which has more than 150 Airbnb units alongside over 500 serviced apartments. This rapid growth is putting strain on local services, small businesses and potentially residents, and there’s a real risk that the people who made the neighbourhood a popular destination for visitors will be pushed out, as the area becomes a magnet for “party lets”, with antisocial behaviour and littering.

With more than 650 potential homes in a relatively small neighbourhood used for the short-term rental market, it’s hardly surprising that the character of the neighbourhood is rapidly changing, while fears grow that it is losing its soul.

Some cities have already weathered the first wave of negative impacts from short-term rentals – and are beginning to fight back. New laws have been put in place, to limit long-term damage to communities. In Paris and London, authorities introduced a cap for short-term rentals to 90 days per year. This helped to ensure that housing built for residents is not taken out of long-term rental markets and used solely as a business asset by owners.

Balconies in Barcelona. Image: mrci_/Flickr/creative commons.

Barcelona has introduced a range of measures, including fines for companies that advertise unlicensed units. Across the world, relatively small “tourist taxes” of £1 per night now include serviced apartments. Proceeds are invested back into cities, to support local services and address the disruptive impacts on neighbourhood life.

So far, English regional cities have been pretty slow to act. Manchester City Council does not yet have a policy to address the sector. Liverpool City Council has been more proactive, pushing for national regulations to force landlords to register short-term rental properties. It has also lobbied central government for the ability to limit rentals to 90 days – a planning tool currently only available in London.

Unless coordinated action is taken at local and national levels, the short-term rental market will make the housing crisis, which is gaining pace in England’s regional cities, even worse. Local communities and politicians need to come together quickly, and learn from cities that have already developed effective policies – before some neighbourhoods change irrevocably.

![]()

Jonathan Silver, Leverhulme ECR Fellow, University of Sheffield.

This article was originally published on The Conversation. Read the original article.