Over the summer, as cities across the US began to examine their role in perpetuating or ending systemic racism, the Los Angeles County Board of Supervisors pledged to adopt anti-racist principles in its policymaking. That commitment became firmer on Election Day when voters compelled the county to reserve a chunk of its budget for social services.

Measure J, which passed with 57% of the vote, requires LA County to allocate 10% of its general funds towards social and community services. Central to the measure is a requirement that this money cannot be used for policing or prisons. Proponents see it as a means of achieving racial and economic justice through fiscal policy and hope the model can be replicated in other cities.

The measure steers funds towards programmes that fall into two broad camps. One is direct community investment in endeavours like youth development programmes and housing vouchers that can help people avoid the criminal-justice system in the first place. The second is alternatives to incarceration such as pretrial and non-custody services as well as community-based restorative-justice programmes. The measure amends the LA County Charter so that after the changes are phased in within four years, they’re guaranteed for the long haul.

Measure J’s success is a product of Re-Imagine LA County, a coalition of community organisations advocating for a vision of justice based on whole-community health instead of punitive-based solutions. Eunisses Hernandez, co-chair of the organisation, says guaranteed funding is what makes the new law so significant.

“We have worked so hard for many years in LA County to move away from a ‘jails first’ and into a ‘care first’ model,” Hernandez says. “The only thing that is keeping us from investing in developing a system of care has been resources. Measure J is the first time we are going to be able to move millions of dollars into things that we have been demanding for over four decades.”

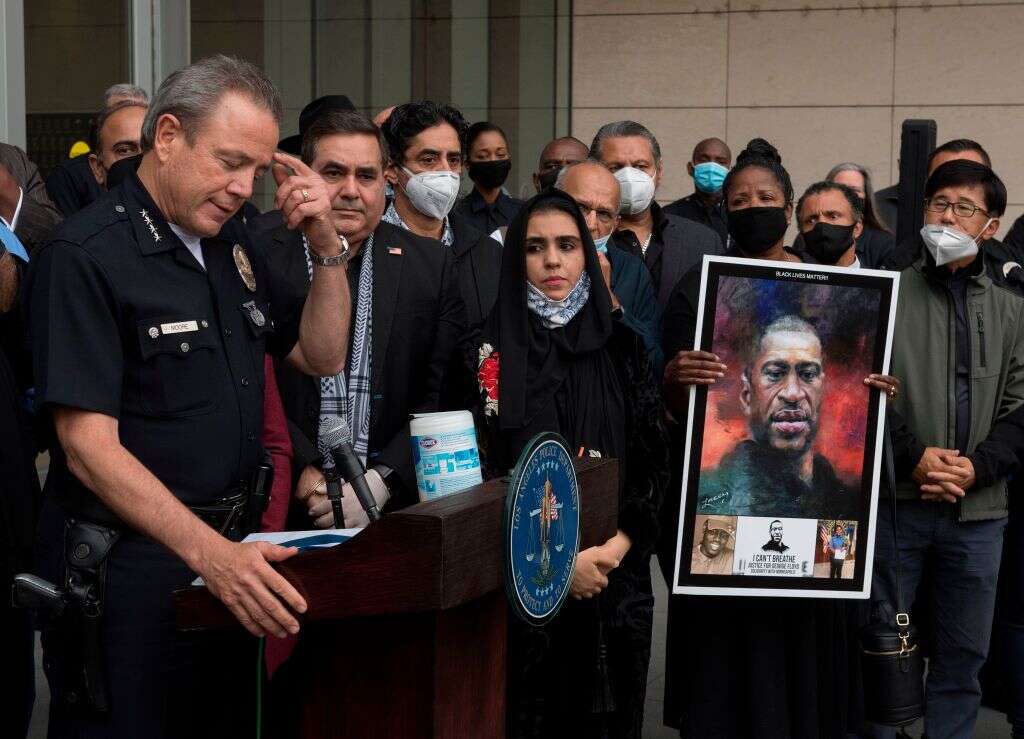

Measure J comes amid heightened attention on the role of police and prisons in US cities. The deaths of George Floyd, Breonna Taylor and other Black Americans at the hands of law enforcement spurred protests against systemic injustice, and calls to reform and even defund police have gained traction. The city council of Minneapolis, where Floyd was killed, voted this summer to dismantle its police force (though no meaningful policy action has followed). Seattle’s city council is currently considering a proposal to cut the police budget by 20%, and New York City, at the behest of protesters, reduced its $6bn police budget modestly.

But the idea of changing policing is contentious within local politics. Calls to reduce police budgets are often met with concerns about public safety, a message that police unions aren’t shy about boosting. Now, despite what seemed like the start of a wave of police reform, not much has changed in most of the country. In fact, many cities have increased their police budgets for the next fiscal year.

It’s worth noting that Measure J does not explicitly call for a reduction in LA County’s law enforcement budget. (Re-Imagining LA County was intentional about steering away from “defund the police” language in crafting the charter amendment.) Still, critics, including LA County Sheriff Alex Villanueva, have said that the reallocation of funds will inevitably take money away from them.

An analysis done by the county CEO’s office found that an across-the-board cut of all other departments to fund Measure J programmes would result in about $114m taken away from the sheriff’s department. But ultimately, the decision of where to cut lies with the supervisors themselves, who thus far have not indicated a willingness to take money away from the sheriff’s department in particular.

The unrestricted general fund that Measure J programmes will draw from is a pool of about $4.9bn based on the 2021 county budget. Re-Imagine LA County estimates that the types of services supported by the measure are currently being funded at $395m. Money set aside under Measure J would be an additional $360m and $396m in the first year and up to $900m when it’s fully phased in in four years.

Law enforcement, by contrast, commands a much bigger share of the budget, as is true in local governments across the US. The LA County Sheriff’s Department alone currently receives about $1.6bn in locally generated funds; $114m taken out of this to fund Measure J programmes would represent a 7% reduction in the sheriff’s budget. Funding for all public protection, including probation and the district attorney, accounts for nearly 40% of all locally generated revenue, as it has for over a decade. In all, LA County spent $8.9bn of its total $36bn budget on public protection in the past fiscal year.

Hernandez says Measure J can rebalance an unlevel playing field, but some opponents take issue with the way it reshapes the city budgeting process. County Supervisor Kathy Barger, the only Republican on the county board, came out against the measure on the grounds that it takes too much power away from elected leaders in allocating money in accordance with priorities of the community.

“Governing bodies should have the ability to budget according to the needs of the region at any given time and have the flexibility to continuously innovate and reallocate as needed,” Barger said in a statement. “The Board has the ability during every single Board meeting (which are open to the public) to increase services and allocations where they are most needed. Tying the hands of the Board undermines the democratic system of government.”

Measure J includes language requiring inclusion and transparency in the process for deciding what programmes get county funds. During a board meeting on 10 November, a week after the vote, County Supervisor Sheila Keuhl, co-author of the motion to put Measure J on the ballot, proposed creating an oversight committee for allocating funds.

The group would include representatives from various county departments, community advocacy organisations, labour leaders and at least five people with “lived experience” of the criminal-justice system. The proposal was passed unanimously with an amendment to ensure that funds allocated under Measure J are done so in accordance with data showing that African Americans are disproportionately harmed by the criminal-justice system.

Hernandez feels confident that this model of ensuring funds for community-based alternatives to prison could work – and is desperately needed – in other cities.

There are already some steps towards similar change in other locales. This summer, Oakland conducted a mid-cycle budget review that cut $14.3m from the police budget and reallocated the money to public-safety efforts, including $1.85m for an emergency-response line for mental health crises that serves as an alternative to 911. New York City will pilot a programme for emergency mental health responders starting in February.

“We can’t stop jail expansion until we decarcerate, and we can’t decarcerate until we build out what we imagine as a decentralised system of care, where you can get access to services in any part of the county, wherever you live,” Hernandez says. “We’re not doing this to move money away from the system itself. We’re doing it because we need to fund things in our communities for our folks to thrive.”

Camille Squires is an assistant editor at City Monitor.