People go out at night because they want to socialise, drink and be entertained. Unfortunately, all too often that leads to violent behaviour in our towns and city centres. But the events that lead to such violence are poorly understood.

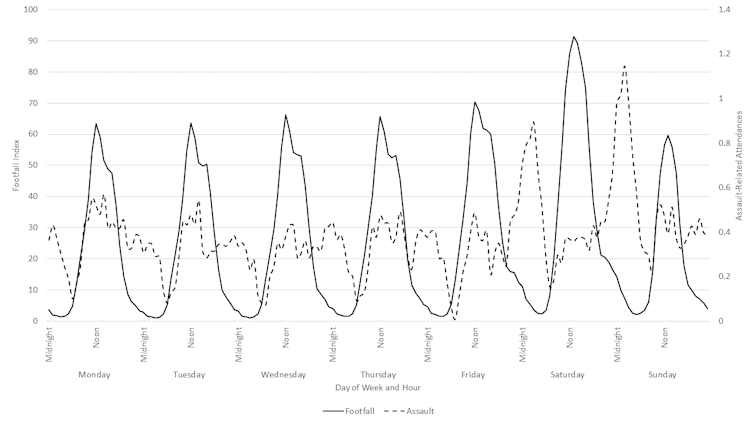

We set out to explore some of the possible explanations of night-time violence using data on Cardiff city centre footfall (the number of people in the city centre) and assault-related attendances at the nearby University Hospital of Wales. We found that a breakdown in the unwritten etiquette of queuing may be one of the reasons behind increases in violence at night.

When revellers gather to enjoy themselves at night, they often drink alcohol and possibly take drugs. This typically sets the activity apart from other places where people gather, such as transport centres or places for other commercial activities such as shopping.

People are attracted to night-time environments based on the total number of social opportunities they provide, whether it’s going clubbing or visiting pubs. So, while entertainment venues compete against one another for trade, they also collectively market to attract patrons from near and far.

The relationship between footfall and assault-related injuries

There has been plenty of research into what reduces or promotes night-time violence in city centres. One of the clear signals of danger is that the larger the footfall in the area, the larger the chance for assaults to occur.

Crowding and noise are associated with increases in violence in city centres at night. And, in Australia, it has been shown that when trading hours are restricted there is a decrease in violence.

But our research shows the correlation between footfall and assault is not linear. In other words, if we double the footfall, we do not simply double the number of assaults. The relationship between these two factors is more complicated, so we decided to investigate what could account for that.

Queue etiquette

One particular aspect we considered was the role drunkenness has to play because it affects how people cooperate, for example when queuing. Queues are a social response to resource competition, whether that resource is nightclub entry, a pint of beer or a taxi.

However, since queuing is a social phenomenon, the people waiting in line have expectations about how others should behave, such as not skipping to the front.

When a violation of those unwritten rules occurs, people queuing in an orderly fashion will seek to defend the queue’s order, with the most vocal complaints stemming from those who are closest to where the person jumps into the line. Although even those ahead of the intrusion may also react to the injustice.

However, whether there’s a queue violation or not, waiting in line makes people stressed. This increases the longer they believe they have been waiting. In turn, such stress can lead to aggression.

To understand the role queues play in the relationship between footfall and assault, we used a mathematical model to help predict what would happen in a variety of night-time scenarios.

We assumed the average arrival time of people in a queue is constant. We also assumed the rate at which they are served and leave the queue is constant, but also rises and falls in line with the number of servers, such as bar staff, taxi drivers or similar.

We also adjusted the models to take into account various other factors, such as weather, bank holidays and whether there were Six Nations or other international rugby matches being played at Cardiff’s Principality Stadium.

We found there was a significant relationship between the number of people in the city centre and the number of assaults recorded in the hospital’s accident and emergency department. The relationship relating footfall with assaults we saw from our queuing models performed better than the simple linear relationship. This is why doubling footfall does not double assaults.

Our study also found events such as bank holidays and rugby matches led to an increase in violence, beyond what might be expected from the impact of footfall alone. Additionally, warmer weather also increased the likelihood of assaults but more rain did not have a significant effect.

Cutting city centre violence

Our mathematical models show that by reducing queuing time, stress and related violence drop too. The average waiting time drops dramatically as the number of servers increases. So when pubs, taxi services or similar are understaffed, that increases the competition between people queuing.

The UK Licensing Act 2003 places a duty on licensed premises to prevent crime and disorder and to maintain public safety. But there are no provisions on how licensed activity should increase as the number of patrons increases.

If further research confirms our observations, then there is a need to address the design and operation of night-time services, not only of bars but of other areas where queues of revellers might form, such as taxi ranks and fast food outlets.

This article by Thomas Woolley, senior lecturer in applied mathematics, Cardiff University; James White, chair professor, Cardiff University, and Simon C Moore, professor of public health research, co-director of Crime and security Research Institute and director of the Violence Research Group, Cardiff University, is republished from The Conversation.