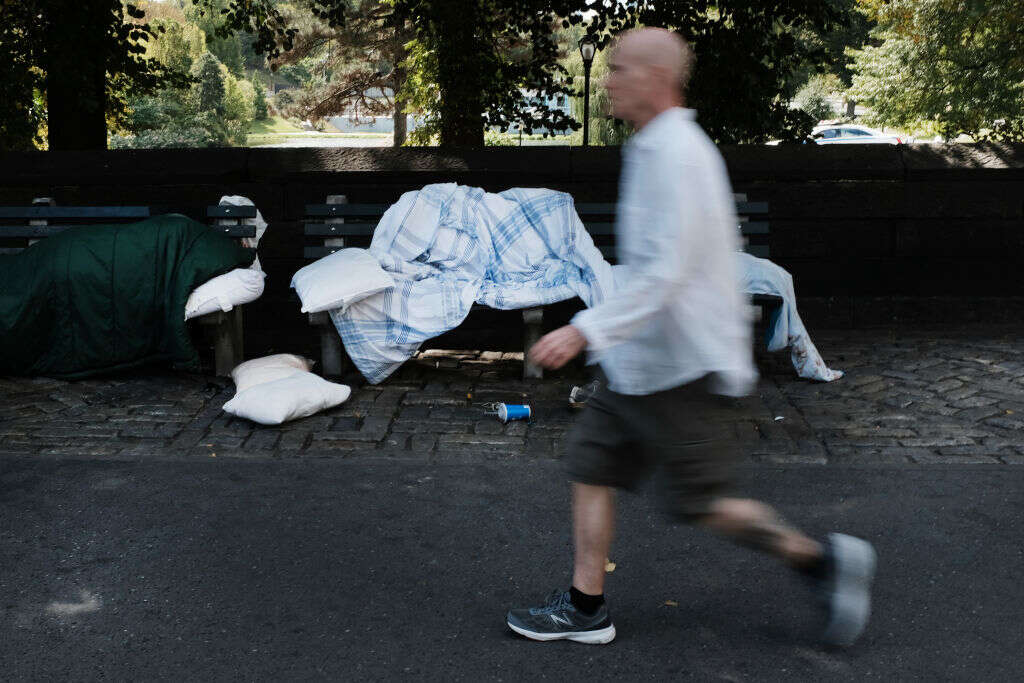

Unhoused people who set up temporary shelters in parks and other public spaces often find themselves at odds with recreational park users and a system that criminalises homelessness in pursuit of public safety.

Cities can shift this dynamic by working to change the view of public homelessness from one of deterrence to one of coexistence. This effort is at the centre of a new report from Spur, a California Bay Area public policy non-profit, and Gehl, an urban design firm. It lays out a road map for a variety of uses for shared public space – intended for everyone from the casual jogger to the unhoused person making an encampment.

Using Guadalupe River Park in downtown San José, California as a use case, researchers conducted interviews with residents, developers and homelessness service providers to understand what about the park currently makes them feel unsafe. They then looked to examples from other urban parks for solutions and identified several aspects of planning that can be addressed to achieve coexistence. These ideas can help communities bring more equity to parks and public spaces.

Designing for inclusion

Design and management can play a big role in determining how inviting or unwelcoming a park can be towards all types of users. Take the issue of lighting, for example: many park users surveyed said low lighting and limited visibility make them feel unsafe at night. A person looking to sleep in a park may also want lighting to feel safe, but too much brightness can be disturbing if they want to sleep. A redesign of Folkets Park in Copenhagen approached this problem by introducing zoned lighting, where some areas are lit only dimly at night, while others remain bright, allowing the park to meet a variety of needs.

As a community, we need to have these conversations around values and decoupling people with behaviours. Michelle Huttenhoff, Spur

The pandemic has moved several city parks departments, including that of San José, to introduce design changes to make parks more inclusive overall, with amenities like handwashing stations, public restrooms and bulk trash cans.

“These seem like things that should have always been there,” says Michelle Huttenhoff, the report’s author and planning policy director at Spur. “If people have an issue with individuals’ bathing in the river, having mobile shower carts is one way to solve for it.”

Decisions about park management and maintenance also factor in. The National Recreation and Parks Association has said that park managers feel overwhelmed by what they see as an addition to their duties – having to act as mental health counsellors and social workers in addition to land stewards. On the other end, unhoused people – especially people of colour – are disproportionately policed in public spaces. One tactic to address this is to engage people with knowledge of homelessness in the work of stewarding public space. A San Francisco organisation called Urban Alchemy has done this, hiring formerly unhoused or incarcerated people who face barriers to employment as place stewards.

Engaging people in a shared space

Establishing rules for everyone to abide by and making sure they are enforced equitably are essential to promoting safety through an equity lens. Instead of enacting blanket laws against loitering, panhandling or camping in public, and enforcing those laws in biased ways, cities have an opportunity to step back and think about what behaviours truly are and aren’t acceptable in a public space.

As a model, the report points to Philadelphia’s Sharing Spaces initiative, which established not only a clear code of conduct and resources for reporting safety violations (not every violation needs be reported directly to police) but also improved access to food, showers and other homelessness services.

Various types of park programming can also engage users of all kinds. This may be as straightforward as offering free board games or as targeted as having a dedicated social worker in a park to foster relationships with unhoused people and connect them with resources. Both strategies have been employed in parks in Atlanta.

Setting the stage for coexistence

At the root of any action to make public spaces more equitable is a need to shift the narrative around homelessness and the people experiencing it, Huttenhoff says.

“It became very clear that as a community, we need to have these conversations around values and decoupling people with behaviours,” she says. Upon reflection, people may realise they don’t actually have a problem with seeing someone else sleep on a bench if there are other surrounding indicators of safety.

“It’s just about stepping back and starting to get specific about what [actions] make you uncomfortable, and less about this group of people,” Huttenhoff says.

Programming aimed specifically at bringing housed and unhoused residents into conversation with one another is one important way to shift this narrative. But it is just as important that this dialogue take place among city leaders such as designers and planners, business leaders and police. That’s why Spur and Gehl have organised their findings into a “coexistence toolkit”, complete with presentation slides and worksheets, to encourage decision makers to undertake the exercise of imagining coexistence. So far, they have presented this model to the San José city government and have received interest from other parks departments. Huttenhoff says she hopes these resources can be helpful not only in implementing policies that serve a greater number of people but in setting a new tone for how to approach the use of common spaces.

“The pandemic has shifted things,” Huttenhoff says. “People are reclaiming their public spaces and going outside, and I think a lot of people are recognising that their public spaces are not equitable.”