Governments are haunted by the threat of corruption. Nothing erodes public trust faster than a predatory elite that hollows out administrative structures and weakens the quality of services.

Corruption is often seen as an especially acute problem in lower-income countries. In developmental economics, a perennial question is whether corruption causes poverty or vice-versa. Even leading middle-income nations like India and China are seen as struggling with a crooked officialdom that hampers economic growth and fuels inequality, while wealthy, established democracies are largely understood to be exempt.

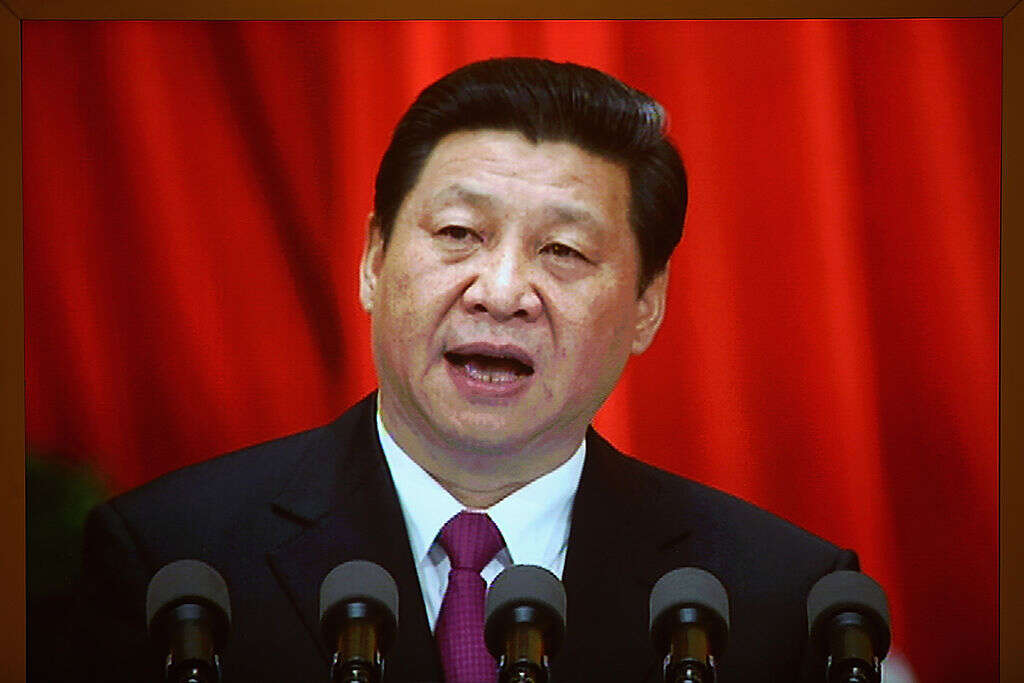

But what if corruption is more complicated than that? Although China struggles with corruption and combating it is one of President Xi Jinping’s central priorities, the country has also experienced tremendous economic growth. Meanwhile, can nations like the US or the UK be considered mostly free of corruption just because it is rare that politicians or police officers take outright bribes?

Professor Yuen Yuen Ang’s book China’s Gilded Age brings much-needed clarity to the topic, helping policymakers determine what kind of threat they are facing. The University of Michigan, Ann Arbor professor breaks down corruption into categories, some of which are outright toxic but others can coincide with or even abet economic growth.

City Monitor spoke with Ang about her definitions of corruption, how the housing market in China is made more unequal by corrupt practices and what the country can learn from the US’s Gilded Age.

The term “corruption” could apply to anything from a city official offering no-bid contracts to a politician raiding a public pension system and shipping the proceeds to a Swiss bank. Let’s start by exploring the Unbundled Corruption Index you created and breaking down the categories so we can understand this phenomenon better.

I propose a typology of four types of corruption divided along two dimensions. The first dimension is whether it involves theft or exchange. The second dimension is whether it involves elites or non-elites. The intersection of these two dimensions generates four types of corruption.

The first is what I call “petty theft” – for example, a policeman shakes you down for protection money. The second type is “grand theft”, like a politician who siphons public funds into his private bank account. The third type is “speed money” – petty bribes you pay to low-level bureaucrats to overcome regulations. The fourth type is what I call “access money”, which is paid to powerful officials, not just for speed but for special deals and privileges.

Access money can either be illegal in the form of massive bribery or it can become legalised and institutionalised – for example, in the form of corporate lobbying.

All corruption is harmful, but each type harms in different ways. I use the analogy of drugs. Petty theft and grand theft can be compared to toxic drugs, like drinking bleach, that have only harm and no benefits. It’s a net loss for society. Speed money is like painkillers. It helps you to reduce annoyance, but it doesn’t help you grow, and taking too many can hurt you. Access money is the steroids of capitalism, growth-enhancing drugs that help you grow big muscles. But they produce serious side effects, and they can blow up in a crisis.

The types of corruption that involve theft are terrible for the economy, but the other two are more complex. What segments of society suffer most from speed money versus access money?

The burden of speed money falls directly and disproportionately on the poor and small businesses. In India today, a typical retail business has to apply for more than 40 permits, and each one provides opportunities for petty bureaucrats to extract bribes to speed up the process. As a result, in India, retail growth is handicapped because that eats into the small margins of small businesses.

By contrast, the cost of access money falls indirectly on the whole society. In China, it leads to excessive speculation in real estate or whichever industry is hot at the time. Politicians help this process by turning a blind eye to risk, by lending excessively to cronies and handing out state contracts. When the economy finally blows up from all of this risk, governments are forced to step in and bail out at the expense of the public.

Let’s talk about how speed money and access money afflict different kinds of developing or middle-income economies. You say that democratic India faces a lot more of the minor regulatory extortion schemes than China’s authoritarian system.

In my research, I show that speed money dominates in India, whereas access money prevails in China because of the two countries’ differences in regime type. India is a fragmented democracy – authorities derive their power from the ability to veto and block decisions. As a result, in India, people pay bribes to override obstacles thrown in their way by bureaucrats. This has a direct impact on the lives of India’s urban residents. They constantly have to battle with petty gripes, bureaucratic harassment and inefficiencies.

You cite a Global Corruption Barometer that shows 69% of respondents in India reported paying bribes between 2015 and 2017, while only 26% had done so in China. How does the dominance of access money in China affect the average resident?

Because power is concentrated in China’s authoritarian system, corruption takes the form of buying access and deals from powerful officials. The effects of this type of corruption are indirect but nonetheless deep. One example is in the realm of housing. In China, because of rampant speculation in real estate, the price of housing has become out of reach for average urban Chinese citizens. One of the biggest paradoxes about Chinese cities is that many people can’t afford apartments, whereas rich people buy many apartments and don’t live in them.

The central government just issued a warning about local government debts, which have crossed a critical threshold where central regulators are really worried that because of the current economic downturn, local governments may not be able to pay the debt that they have accumulated in the process of trying to build a lot.

That’s a long-term side effect of access money?

Absolutely. The central government warns that the ratio of local government debt to their total revenue is at 100%. Which means these governments owe as much money as they make. This is the kind of risk that the Chinese government is facing at this point, which is connected with an excessive amount of speculative activity and inaccessible housing.

A lot of Western policymakers and international agencies recommend that developing nations pay bureaucrats a living wage as a means of fighting corruption. Or that they purge patronage appointees from overstaffed agencies. But a lot of countries don’t pay bureaucrats a living wage because they don’t have the tax revenues. Or think of a country like Lebanon, where patronage underpins the whole political system. Getting rid of it would create political instability. How did the Chinese work around those expectations in terms of professionalising and paying the bureaucracy. Could that model be applied elsewhere?

China’s administrative reforms in the post-communist era had a distinctly pragmatic flavour. It was a mixed bag of whatever the leaders thought would work for the situation. On the one hand, they sometimes do carry out what would be called “best-practices reforms”, like eliminating cash payments or introducing more transparency into public budgeting.

These are standard best-practices reforms, which they carried out effectively and comprehensively. But at the same time, alongside these best practices, within local governments, they also improvised what I call “transitional administrative institutions”. These are strategies that are neither best practices nor dysfunctional corruption. It was in between.

In China’s context, instead of compensating local bureaucrats by paying them a standard and adequate formal wage using tax revenue, these bureaucrats receive variable amounts of supplemental allowances and perks linked to their ability to generate revenue. Over time, as local governments became richer, this transitional system was phased out and replaced with formal wage payments from state budgets. If you look at China even today, the actual level of public compensation varies widely across regions, sometimes even within a single province.

I’m not encouraging other countries to copy exactly what China did. I think that’s a common fallacy of thinking that if it works in China, we’ll do exactly that. I should stress that this practice of profit sharing arose in Chinese bureaucracies because it fit the conditions in the country at the time. Instead of trying to unrealistically impose best practices or copy China, other countries should explore transitional solutions that fit their own conditions.

You highlight dry-sounding reforms that were passed in 1998, when the party instituted policy changes that undermined the most predatory forms of corruption. Cash payments of fees were eliminated, civil-service requirements instituted, public budgets made subject to transparency requirements. All this made cases of speed money and theft plummet, while access money soared. How replicable do you think those results would be in other developing countries? Is it possible without a strong authoritarian state?

One condition for these reforms is a strong state committed to administrative reforms. But I don’t think that only authoritarian governments can accomplish this, because similar reforms were carried out during the Progressive Era in the US in the early 20th century. The professional civil service that we now take for granted was established because Americans were fed up with rampant corruption and the repeated financial crises that resulted from it.

A commonality between China after 1998 and the US’s Progressive Era is that both of them were emerging markets that had already taken off. They had already experienced economic growth. They had resources and the desire to build better institutions for sustained growth.

You draw a lot of comparisons between the US in the 19th century and China today. But you say China’s excesses are intensified by the one-party state. Why is the Gilded Age in China even more extreme than that in the United States? Why is inequality higher there than in the US or UK today, which are experiencing what some call a second Gilded Age?

During the US’s Gilded Age, however corrupt it was, there was still political freedom. Politicians could be voted out of office. There was a free press, which was a powerful check on excesses of corruption, particularly during the Progressive Era. Investigative journalism played a big role in exposing scandals and collusion, and building up public support for serious reforms. These checks are lacking in China. As a result, citizens do not know about scandals until they are completely out of hand. For China’s rulers, this is also a problem because freedom of reporting is suppressed and so they themselves lack accurate information on the ground.

I’ve seen it argued that Xi Jinping’s anti-corruption campaigns, which are a centrepiece of his governance strategy, are more a political purge than a genuine anti-corruption campaign. You’ve done original research on this front. What did you find?

The current anti-corruption campaign is partly a purge and partly a real effort at controlling corruption. In one chapter, I look at the factors that predict which city-level leaders were investigated for corruption during this campaign. There are two key findings. The first is that patronage, not performance, predicts the likelihood of downfall. If a provincial leader who appointed a city leader is himself investigated for corruption, then the chances that his clients will get into trouble dramatically increases.

At the same time, however, I find that when a member of the Politburo – which is the highest ruling party in China – falls from office, not all of his clients fall with him. If you think that the campaign is only a purge, we should expect that when a Politburo member falls, all of his clients fall. But that doesn’t happen. All together, the evidence tells us that patronage is the most important factor behind a politician’s fall or survival. But it’s not a 100% predictor.