This article appears on City Monitor courtesy of Blueprint magazine.

In mid-March, Italian authorities began setting up tents outside hospitals to handle an influx of patients with Covid-19. Other places soon followed suit: A 14-tent field hospital opened in New York’s Central Park on 1 April, built in just 48 hours. The same day, London’s St Thomas’ Hospital started erecting its own tent to expand its capacity to treat coronavirus cases.

With the virus continuing to spread rapidly around the world, governments and medical facilities are scrambling to keep up with the growing demand for intensive care facilities and ventilators, and these tents are part of the response.

They’re a quick solution, but an inadequate one, says the Italian architect and MIT professor Carlo Ratti, because it is impossible to effectively contain pathogens within the open structures.

“Biocontainment is very important for Covid-19 as it traps the virus and creates a less dangerous environment for health care professionals,” says Ratti, founding partner of CRA-Carlo Ratti Associati.

He has been working as part of an international group – including the architect Italo Rota, Humanitas Research Hospital, Policlinico di Milano and the US engineering firm Jacobs – to develop an alternative: a series of compact, 20-foot-long, self-contained modules built out of shipping containers.

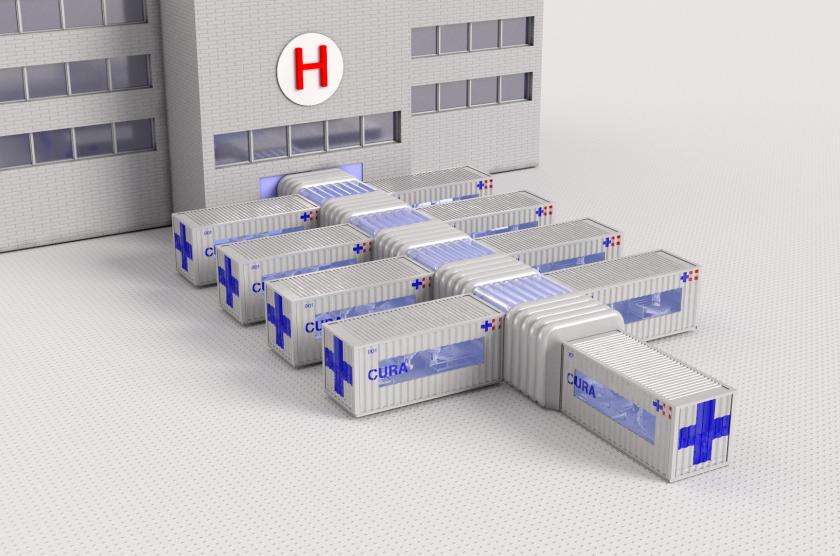

The units are called CURA Pods, an acronym for “Connected Units for Respiratory Ailments” that also means “cure” in Latin. Each of the pods is equipped with a ventilation system that creates a negative air pressure within them: air can only flow inwards, which means the virus cannot escape. The designers say the units comply with the standards required of airborne infection isolation rooms, which prevent cross-contamination between hospital rooms for patients with contagious airborne diseases. The pods would come with all the medical equipment needed to treat people battling coronavirus.

Shipping containers are often lambasted for being a knee-jerk architectural response disguised as a sensitive, sustainable solution – offered by many designers as a literal one-size-fits-all building block for everything from housing to co-working spaces to industrial and commercial units, regardless of whether their boxy, airless nature is desirable or suitable for the purpose.

In this instance, however, those very qualities are most valuable, not only allowing for biocontainment, but enabling the units to be combined together easily in a modular formation using inflatable corridors, so that hospitals around the world can rapidly scale up and down their capacity during this time of crisis. The idea is that the pods could be attached to hospitals – perhaps set up in their parking lots – or as standalone facilities in open spaces, configured to suit the space available, offering just four beds or more than 40.

In keeping with the rapid spread of the virus, the designs were developed at speed, coming together in just a couple of weeks. This was partly due to to a conscious effort not to reinvent the wheel. “We didn’t aim to invent something new – rather, we want to improve the efficiency of existing solutions in the design of field hospitals, tailoring them to the current emergency,” Ratti says.

Nonetheless, working on the project in the era of social distancing was a problem in itself. “One of the main challenges was not being able to meet in person,” Ratti says. “Remote working isn’t always easy to manage, especially when it comes to co-designing with more than 100 people from different countries and continents.”

At the time of writing, the first operational CURA Pod has just been installed at a temporary hospital in Turin and funded by UniCredit. The team estimates each unit can be produced for about €75,000 per bed. The idea, however, is for the initiative to take on a life of its own. The designs are being shared for free online, in the hope that they will be copied around the world.

For the sake of speed and given the current restrictions on movement, not to mention environmental impact, this seems a more appropriate solution than shipping ready-made modules. Still, local manufacturing will no doubt be difficult in many places, given the disruptive impact that coronavirus has had on global supply chains.

Ratti is hopeful, however, that CURA Pods will help smooth out some of the logistical roadblocks that stand in the way of curbing the pandemic. “We hope that our work can be of inspiration for more people around the world to take action.”

Debika Ray is a writer living in London.