There was once a time when Cristina, like many bar managers in Spain, would have concluded her evenings sweeping up dozens of used serviettes off the floor of Alces, her family’s popular bar in central Madrid. However, since June, this has not been the case.

Following one of the most stringent lockdowns in Europe and the onset of its so-called “new normality”, Spain banned common-use items in bars and restaurants such as salt cellars, bottles of olive oil and, most importantly, serviette holders due to their potential to become breeding grounds for coronavirus transmission.

In Spain, a country where hospitality and tourism represent 6.2% and 12.3% of national GDP, respectively, serviettes and their classic metal holders are interwoven into Spanish tapas culture. This is to such an extent that bars and cafeterias traditionally feature their own logos on these tiny, 17cm x 17cm sulphite paper squares. Their use (or, currently, lack thereof), has far-reaching societal, economic and environmental consequences.

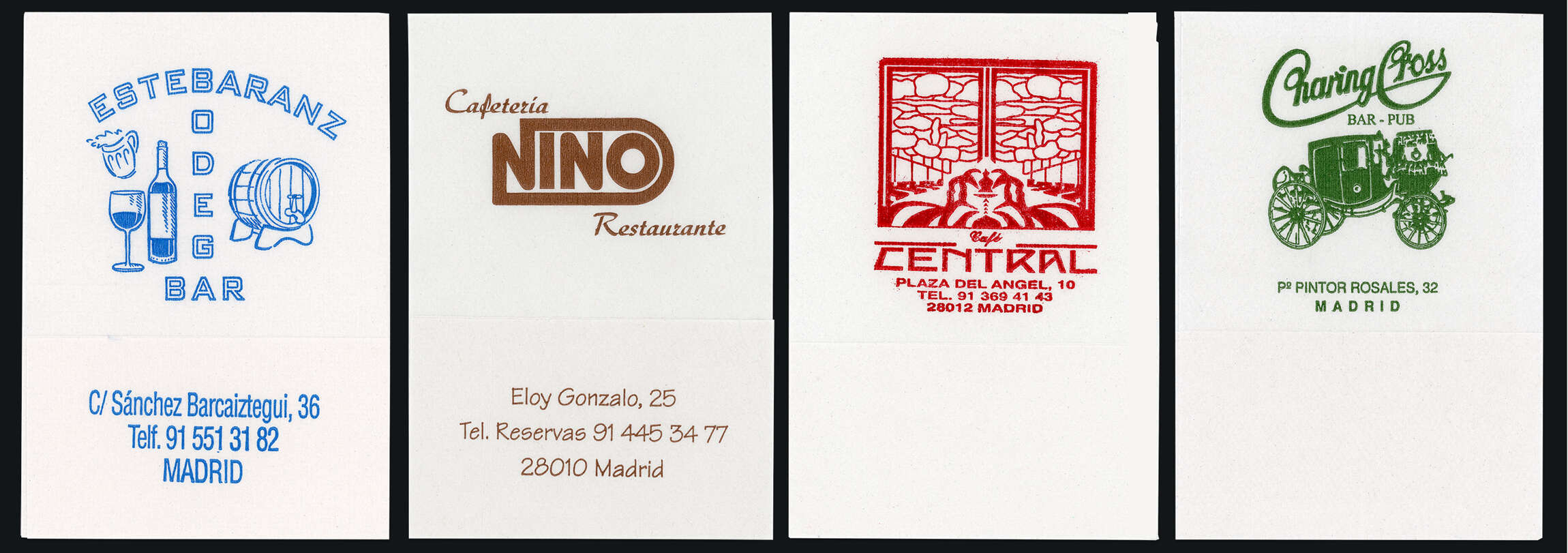

“Spain’s serviette transcends all regional gastronomies, provinces and social classes. Whether you’re eating shellfish in Madrid’s upmarket district of Salamanca, paella in Valencia, a pintxo in Bilbao or simply eating fried grub in your local bar, it unites Spain,” states Felipe Hernández, a Spanish photographer, who has collected over 500 individual serviettes and regularly documents them on his Servilletas Instagram page, which he started curating back in 2014. “They have an advertising purpose and are instantly recognisable thanks to their different fonts, icons, colours and designs.”

However, it is this seemingly banal item that has unexpectedly become one of Spain’s most notable and high-profile cultural victims of the pandemic to date as the conviviality of the country’s once-crowded bars has been put on pause. Could this offer an opportunity to rethink traditional patterns of consumption?

“We’ve seen a 73% fall in sales of mini-serviettes,” says Belén González, CEO of Mapelor, a paper manufacturer based in Alicante. Last year, Mapelor produced over 367,000,000 mini-serviettes – a mind-blowing figure for just one type of napkin from a single paper manufacturer. The absurdity behind these numbers, in a country of 47 million, is that despite their historic and widespread usage, these products are notoriously poor at soaking up grease and oil, rendering them unsuitable for Spanish fried cuisine and ultimately leading to endless waste.

González explains that these miniservis have traditionally been the serviettes of choice for many bars purely because they tend to be the cheapest. However, as she points out, this is a fallacy, as customers cleaning their oily fingers are usually forced to use more than just one due to their lack of effectiveness. Ostensibly a budget item, they ultimately drive up costs for bars and generate a huge negative ecological impact.

Now that Covid has brought about a ban on the serviette holder, some observers have begun to reflect on the wastage associated with the napkins. Others have been thinking about this for a long time. One of those people is Pablo José Galcerán, CEO of Tachett, who in 2016 was sitting on a terrace in Mataró (Catalonia) when a gust of wind caused the serviettes on his table to go flying and litter the terrace with paper. As he chased after the napkins, seven crumpled ones in hand, he realised the repercussions of their widespread use.

Galcerán’s research showed that Spain’s waiters spend an average of 13 hours a month handling used serviettes. “Serviettes don’t just pollute, they also cost time,” he explains. So he engineered a solution: a reusable, ecologically friendly rubbish bin that can be fixed to any holder, where diners can discard such paper waste as serviettes and sugar sachets.

Galcerán asserts that there are currently over 300,000 eateries in Spain, each using 200kg to 300kg of paper a year, none of which is being recycled. However, according to initial estimations provided to him by Catalonia’s waste agency, his patented wastepaper basket could lead to a 15% increase in recycling across the region.

But for many in the country, recycling doesn’t go to the heart of the issue.

“There is an excessive use of serviettes in Spain due to a lack of awareness and due to restaurants providing poor-quality and thin napkins, which compel you to use more than just one,” explains Isabel Coderch, CEO of Te Lo Sirvo Verde (I Serve It Green), a consultancy for sustainable food service.

This can certainly be attested to by Cristina, who admits that she’s never actually considered the environmental impact of the miniservis used in her family’s bar. When asked why Alces has continued to use them despite knowing they’re ineffective, she admits that it’s just tradition.

It’s not that Cristina and her family are ignorant to environmental concerns, though. Last year, they made a conscious decision to switch to paper bags for takeaways after Spain started charging for plastic bags in supermarkets. The will is there, the awareness has not yet caught up.

Coderch says part of her work at Te Lo Sirvo Verde is based on educating and drawing up waste prevention schemes for eateries. She explains that serviette wastage can be cut down simply by using dispensers that allow diners to take just one at a time and not leaving stacks of them on top of a bar.

Spain’s serviette dilemma is not strictly limited to the hospitality industry, however; it is also endemic in school dining halls, hospitals and work canteens. For Coderch, the solution lies in striving for zero waste and understanding that “sustainability isn’t a target but rather a never-ending journey towards improving”.

Mapelor is already on that journey, having eradicated all its waste sent to the landfill. In 2019, it became Spain’s first and only zero-waste paper manufacturer and now produces various serviette lines, which are 100% compostable, biodegradable or made from 100% recycled materials. What’s more, some of its serviettes now feature slogans on them (in natural inks) to discourage waste.

Ultimately, meaningful change will come only from government regulation, explains Adriana Espinosa, head of waste and natural resources at NGO Friends of the Earth. She says Spain is in the midst of drafting a new bill to update its “obsolete” 2011 waste law in order to incorporate both the EU’s Waste Framework Directive and its Single-Use Plastics Directive.

Friends of the Earth believes the bill should look further than just plastics and make provisions for other single-use items commonly used within hospitality, such as serviettes, which “ultimately pollute all the same”. Likewise, Espinosa states that sometimes “we have a tendency to dream up ingenious technological solutions for problems which could simply be solved by reducing usage”.

Current coronavirus regulations are giving Spain an enforced reprieve from its serviette conundrum; the true test, however, will be when napkin holders are allowed back on tables and bars across the country. But with Spain’s hospitality sector suffering greatly from the pandemic’s economic fallout, paired with unaffordable rents and reduced capacity, serviettes may largely pale into insignificance.

“Many bars and restaurants in the centre of Madrid have closed,” says Cristina. “At least we’ve had the terrace, but we are worried about the winter.” This is to say, serviettes may ultimately just be collateral.

Jamie Broadway is a British freelance journalist based in Madrid.