Statistics from food banks across England show a frightening rise in the number of people using their services, meaning that more and more people don’t have enough money to feed themselves. Between 1 April 1 2016 and 31 March 2017, the Trussell Trust provided 1,182,954 three-day emergency food packages – up 73,645 from the previous year.

People affected by food poverty face severe threats to their health and well-being. As well as the stress, depression and anxiety that can result from not having enough money to feed their families, people experiencing food poverty also face a higher risk of obesity, because the only foods they can afford tend to be cheap, sugary, processed and fattening.

Some researchers have already mapped out who is using food banks, which is a big step towards understanding the problem. But academics like ourselves are increasingly concerned that just focusing on food bank data means we are not seeing the whole picture. After all, some people in need do not live near a food bank, or do not know about local services, or are too embarrassed or worried about what will happen if they tell people they cannot afford to feed their children properly.

These people are extremely vulnerable, since they’re not getting the crucial emergency support offered by food banks. Identifying and helping the unseen victims of food poverty should be a national priority. The obvious answer is to create a national measure of food poverty, like the ones used in the US and Canada. This would allow the government to identify those in need, and target resources accordingly.

Shockingly, no such measure is used in England, though some efforts are being made in Wales and Scotland. But there is a way to use existing data, to figure out not just how many, but crucially where vulnerable people might need emergency food.

Mapping out food poverty

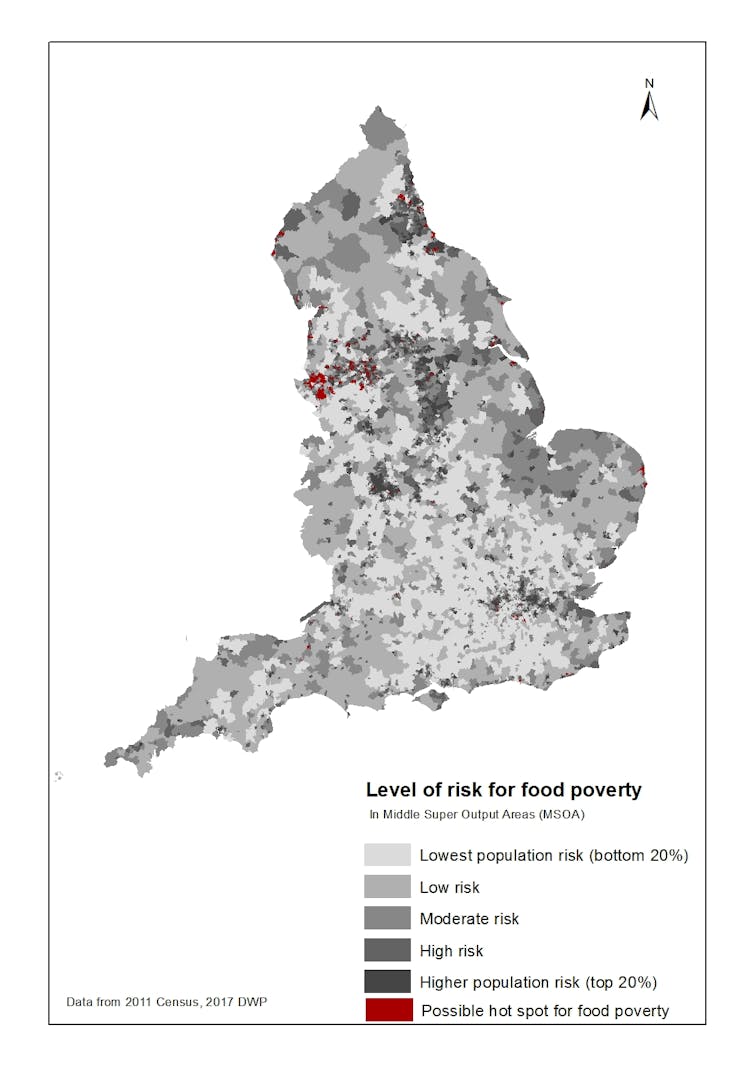

We already know what types of people are more likely to experience food poverty: single pensioners, low income households with children and people claiming benefits are at greater risk. By combining this knowledge with big datasets such as the Census and data from the Department for Work & Pensions, it’s possible to find out where populations at risk of food poverty live.

As part of new research, we mapped out the number of people at higher risk of food poverty across all of England. Our map shows that some areas of the country face much higher levels of risk – and they’re not always the ones you might expect.

A map of food poverty across England. Image:Dianna Smith and Claire Thompson/author provided.

For example, when we updated our maps with the most recent data on benefits claimants, we found that areas in London such as Croydon and Southwark have a large proportion of residents facing a high risk of food poverty. Outside of London, some urban areas in the north (Liverpool, Manchester, Newcastle) have higher risk – even where these areas don’t always appear to be deprived using other measures.

When we compared those areas where people are at higher risk of food poverty with the locations of food banks from the Trussell Trust, we found that those areas don’t always have a lot of food banks. In fact, based on the available data, we couldn’t find a statistical relationship between the number of food banks in an area and the 2015 Index of Multiple Deprivation score, meaning that food banks are not always concentrated in the poorest areas.

Making a difference

Of course, this is not a criticism of food banks. They offer vital and often life-changing services. But more information about exactly where these invaluable services are needed could mean more vulnerable people receive the help and support they need to get through a difficult time.

Our maps can help with this, by helping local authorities put together food poverty action plans that target their resources more effectively. The data can be tailored for localities to account for the specific local problems which contribute to food poverty – such as the high housing costs in London boroughs, and the high rates of unemployment in many communities in the north-east of England. We are already working with local authorities around the country to this end.

![]() This type of work is becoming more important, as controversial policy changes and cuts take hold. The roll out of Universal Credit looks set to make food poverty worse in some areas. By looking for food poverty hot spots in the local communities, researchers can help charities and local government to reach those in need.

This type of work is becoming more important, as controversial policy changes and cuts take hold. The roll out of Universal Credit looks set to make food poverty worse in some areas. By looking for food poverty hot spots in the local communities, researchers can help charities and local government to reach those in need.

Dianna Smith, Lecturer in GIS, University of Southampton and Claire Thompson, Assistant Professor, London School of Hygiene & Tropical Medicine.

This article was originally published on The Conversation. Read the original article.