Organisations including #BlockSidewalk and the Canadian Civil Liberties Union orchestrated a powerful resistance movement against Sidewalk Labs’ Waterfront Toronto project amid concerns over the Alphabet-owned company’s handling of issues such as data collection and surveillance. Now that Sidewalk Labs has pulled out of Toronto, these same groups are turning their sights on big tech’s newest public infrastructure endeavour: contact-tracing technology.

In May, Sidewalk Labs announced that the company would no longer be pursuing the Quayside project, citing “economic uncertainty” caused by the Covid-19 pandemic. Local activists, however, had been anticipating an end to the project for months, after the city forced the company to scale back its plans in October.

The #BlockSidewalk campaign, a coalition of community members, technologists and business owners, formed in the fall of 2018 in response to the lack of transparency that surrounded the project. From its inception, the plan had drawn criticism from community members and sceptics abroad, who pointed out that Sidewalk Labs’ failure to identify systems of ownership and management for the steady stream of fine-grained data required to run its digital infrastructure would leave Toronto residents vulnerable to privacy breaches. Throughout the project’s development, Sidewalk Labs struggled to shake its association with its sister company, Google, whose history of user data collection worried those with a post-Cambridge Analytica perspective on Silicon Valley.

The Sidewalk saga is the latest occurrence in a wider “techlash” in many cities, a groundswell of scepticism toward technology companies which also helped put a stop to plans for the establishment of Amazon headquarters in Long Island City, New York, and Google offices in Berlin. #BlockSidewalk, alongside other resistance groups, has in several ways created a new system of accountability and community oversight over municipal procurement and local implementation of technologies.

For Bianca Wylie, an outspoken technologist and founding member of #BlockSidewalk, the Sidewalk Labs experience revealed years of neglect on the part of Toronto legislators in creating policy surrounding digital governance. “This stuff is not new… What [#BlockSidewalk] did was provide that tension – it created friction in the community and got people to show up and challenge the government, which currently lacks a lot of technical capacity,” Wylie says. “So finally you have people who work in tech partnering with communities, who are not only asking, ‘What’s the deal with this Sidewalk tech?’ but also, ‘What about technology in cities are we not getting a chance to imagine by letting private companies do it for us?’”

Resistance and the sunlight it provides can be a tool for political change, one that #BlockSidewalk now says needs to be mobilised once again as high-density urban areas become testing grounds for private technology companies scrambling to provide contact-tracing technology to governments.

In places such as Taiwan and South Korea, which have become global models in the fight against the coronavirus, contact-tracing technology has played a crucial role in tracking and containing Covid-19. To effectively monitor citizen behaviour, these systems rely on a rigorous surveillance infrastructure. In early March, South Korean officials announced that they would be employing a “Smart City Data Hub” that the government has been developing since 2018. The hub provides access to urban data that is used in tandem with CCTV footage, mobile-phone location tracking and credit card transaction information to populate text messages to citizens that detail the exact movements of local infected individuals, providing information on their age, gender and a minute-by-minute log of activity.

While surveys have found that the South Korean public supports the government’s sharing of location data in the context of the pandemic, privacy is a major concern for other countries looking to implement contact-tracing technology. In early May, Google and Apple announced they would be partnering to build a decentralised, Bluetooth-based system of contact-tracing technology that would be built into their mobile-phone operating systems. To establish a standard of privacy, the framework for the companies’ API was based on Decentralized Privacy-Preserving Tracing (DP-3T), an independent contact-tracing project developed by a cohort of privacy researchers and technologists across Europe. The technology works by providing the tools for governments to build contract-tracing apps to track proximity via a system of anonymised Bluetooth keys and push “exposure notifications” to those who have been exposed to someone who has tested positive for the virus.

The API’s initial release was met with opposition, as some countries, such as the UK, pushed for a centralised model that would provide government and public-health officials with more control over data in spite of the general public’s concerns over privacy. In the months since, 13 countries, including Italy, Malaysia and Japan, have either deployed or begun development on contact-tracing applications that utilise Google’s and Apple’s API, with countries such as the UK and Germany returning to the API after initial resistance.

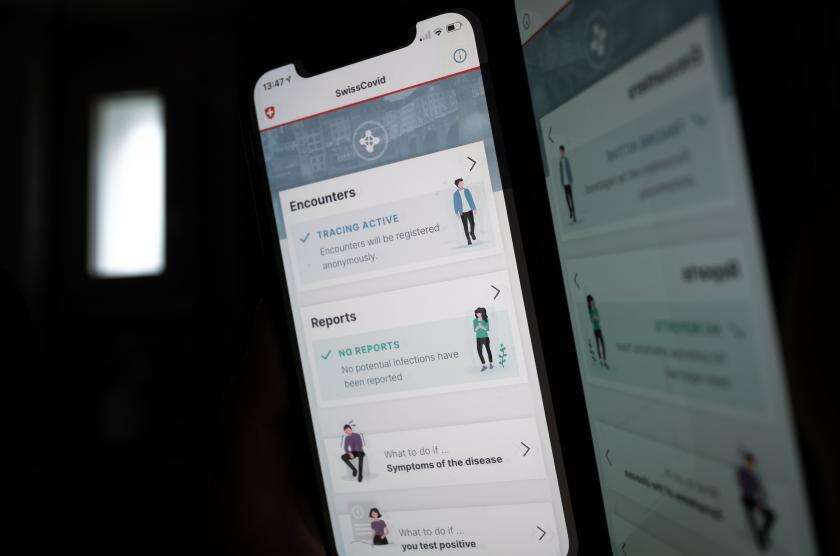

For the most part, these apps have been received positively by the general public. Japan’s COCOA (Contact-Confirming Application) saw four million downloads within its first week, and in Switzerland, about 12% of the country’s population has downloaded the SwissCovid contact-tracing app, a collaboration between Google and Apple as well as DP-3T, within weeks of its release.

Still, these numbers are nowhere near the 40% adoption rate experts have identified for contact-tracing apps to effectively contain the virus. In an interview with Radical AI, Seda Gurses, a professor at TU Delft and a contributor to DP-3T, warned that governments should be wary of forfeiting the construction of digital infrastructures to large tech companies for apps that may not work, arguing that doing so could exacerbate inequities. “Fairness assumes that we universalise some sort of objective for algorithms, but these computational infrastructures [large, private tech companies] were building a very unfair society [before Covid-19] even as they were claiming they could make their algorithms fair,” she said.

In the United States, momentum surrounding contact-tracing apps has slowed in the wake of protests and rising dissent in response to the police killing of George Floyd in Minneapolis. In a press conference held in early July, the commissioner of the Minnesota Department of Public Safety alarmed privacy advocates when he compared police departments’ investigative work into protester activity to contact tracing. According to Daren McKelvey*, director of marketing and communications for the exposure notification app Coalition, missteps like the Minnesota commissioner’s false insinuation, or cases such as North and South Dakota’s bungled rollout of its Care19 tracing app, are harmful to the overall objective of contact tracing, “[It] hurts public health, it hurts public trust. We’re open to working with governments and we know that it is essential, but we are honestly very wary of what their intentions are as well. We don’t want people’s data to be used [incorrectly]”.

Coalition, whose Bluetooth framework has been used in both France and Sengal’s contact-tracing efforts, is a non-profit application created by the developers behind Nodle and FireChat. According to the blockchain architect Eliott Teissonniere, who co-authored Coalition’s Whisper Tracing Protocol, public education on how contact-tracing apps work is essential to building public trust and buy-in.

“People need to understand that our protocol is built so that even [our company] cannot see the data, it’s not a matter of exchanging names for Bluetooth identities,” he says. “We don’t even see who the people are. [Our technology] generates proof that two people met and that’s all. We don’t record who the people are. There is not even a central database that we or the government can access to find this information”.

Nigel Jacobs, a civic technologist who heads Boston’s New Urban Mechanics office and served as a consultant for Sidewalk Labs, notes that product development companies attempting to work in the public right of way often face backlash due to the incongruity of business objectives with consensus-building practices. “[They] already know what they want to do, they have these products that they have designed and are trying to roll out. So what is the point of public engagement meetings, when you are coming to the table with all the answers?”

A recent survey found that only 30% of American smartphone-owners indicated that they would download and use a mobile contact-tracing app. Among Black smart-phone owners, a group already disproportionately affected by Covid-19, only 22% indicated that they would be likely to download a tracing app, compared to 32% of White Americans.

Covid-19 has laid bare the racial disparities in public health and healthcare. As communities of colour continue to be disproportionately affected and protests against systemic racism rage on in American urban centres and beyond, it has become clearer than ever that our cities were never built equal. Thus the data-gathering systems for optimising public health and the built environment as they are proposed may never add up to the impartial tools of arbitration they are sold to be.

For governments and companies with plans to roll out contact-tracing technology, there must first be an awareness of the barriers that will stand in the way of successful adoption. According to Jacobs, who has consulted on some of Boston’s contact-tracing-technology initiatives, it is a matter of building trust holistically on the ground, something that big technology companies struggle to do. “You have to be willing to build bridges to people,” he says. “It’s coming to them with an understanding that previously they may have had a reason to distrust public-health officials and police officers. In having these conversations, you have to be aware that no one is going to download an app put out by city hall if they can’t even trust you to do normal things like pick up the trash.”

*Correction: This article originally misspelled the surname of the director of communications for the app Coalition. His name is Daren McKelvey.

Isabel Ling is a freelance writer based in Brooklyn, New York. Her work has also appeared on Eater, the Verge and Hyperallergic. Follow her on Twitter.