Most of the 20m fines issued every year by municipalities in Italy are for illegal parking, speeding, entering bus lanes or skipping congestion charges. They account for about 15 per cent of non-tax revenues for local authorities, bringing in €11 per capita a year.

But I’ve found that Italy’s mayors tend to act with far greater leniency towards unruly drivers when an election approaches.

Elected governments all over the world time policies to maximise their chances of re-election. Raising the pay of civil servants or cutting taxes delivers greater returns for a party if announced just before it faces a public vote. Unpopular reforms, meanwhile, are more likely to be implemented in the first part of a term in government. This is known as the political budget cycle.

I collected data from municipal budgets and elections over the past 20 years, looking in particular at how many parking tickets each mayor issued, and how much money they actually managed to collect. I divided mayors into two groups according to their so-called “electoral incentives” – that is, whether they feel their re-election is at risk.

There are a number of ways to measure these “electoral incentives”. The simplest is to consider the margin of victory with which the incumbent won the previous election. Mayors elected with just a few votes more than their challenger are bound to be under stronger pressure in the incoming elections. I also looked at mayors who are at the end of their term and close to facing another election, as opposed to mayors who are freshly elected.

Just like US presidents, Italian mayors are barred from seeking re-election after their second term in office, so I also compared mayors in their first term (and therefore seeking re-election) with mayors in their second term (barred from running).

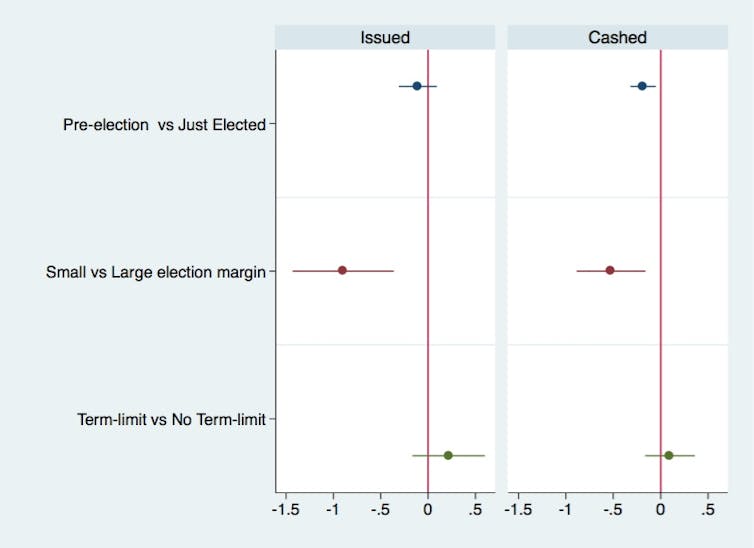

Effect of Electoral Incentives on traffic enforcement. Average Euros per capita. Lines are 95 per cent confidence intervals.

Mayors elected with a small margin of victory issue almost €1 per capita less in fines, and cash in about 50 euro cents less than those who won elections with a wide margin. Mayors who barely won their seat don’t seem to want to disappoint those precious marginal voters and put their own re-election at risk.

Mayors in their second (and last) term in office are slightly more strict. By law they cannot run for a third term, so perhaps they feel more free to charge drivers. They know they won’t pay an electoral cost as a result.

Last, we look into the third way to pinpoint political budget cycles, by comparing mayors nearing the end of their term in office with those who have just been elected. The former issue roughly the same amount of fines as colleagues at the beginning of their term, but they cash on average 18 euro cents per capita fewer per year. This may not seem very much, but would account for about €1.5m in a year for municipalities such as Milan or Rome. The closer the elections, the more lenient they get in chasing undisciplined drivers. They seem to be trying not to bother drivers just as they are deciding how to cast their vote.

![]() The moral of the story is that if your mayor fears for their re-election you’re less likely to get a ticket for your parking indiscretions. You’re also less likely to be chased for payment if you do get one.

The moral of the story is that if your mayor fears for their re-election you’re less likely to get a ticket for your parking indiscretions. You’re also less likely to be chased for payment if you do get one.

But of course, you’d never park where you shouldn’t anyway, regardless of when the next election is. Would you?

Emanuele Bracco, Senior Lecturer in Economics, Lancaster University.

This article was originally published on The Conversation. Read the original article.