Buses are Britain’s most frequently used form of public transport: last year, 4.4bn bus trips were made across England, and buses account for 59 per cent of all public transport trips in Great Britain (compared with 21 per cent by rail). But since 2010, local authority funding for buses has halved, and thousands of services have been cut.

This affects everyone, but especially people on low incomes, the young and the elderly. Without immediate action to halt the decline of Britain’s buses, many could be left without a way to access vital services and opportunities – and ultimately, excluded from society.

In England, the young and the elderly collectively account for nearly half of all bus passengers; children under 16 account for 19 per cent, and those aged over 60 account for 25 per cent. Fewer bus services mean their travel options shrink significantly. Working age people – that’s 21- to 59-year-olds – tend to travel more by train.

England’s lowest income people also make 75 per cent of their public transport trips by bus. If we divide the population up into five groups – from the lowest income, to the highest income – then the lowest income group makes three times as many bus trips as the highest income group. By comparison, the highest income group make 20 per cent fewer public transport trips and 75 per cent more private transport trips, while travelling more by train than bus.

Bus services are particularly important to those without access to a private car or van. For them, bus journeys make up 43 per cent of motorised trips – compared with just 4 per cent among people who have access to private transport. Those lower-income households without a car or van also made 30 per cent fewer trips overall in 2016.

But even those households with a car or van suffer from poor public transport options: around 9 per cent of all UK households have a low income but high motoring costs. Without good public transport, these households have no option but to find savings elsewhere, to meet the cost of driving.

How did it come to this?

Outside London, England’s bus market was deregulated and privatised in the mid-1980s, which means that local authorities don’t plan and manage the bus network. Instead, private bus operators decide where, when and how frequently to run buses. Since bus operators are focused on routes that can deliver a profit, the service can be sparse, and tends to be focused on peak hours.

Local authorities can choose to fund socially inclusive bus services to complement the for-profit network – but these services have been hit particularly hard by successive governments’ cuts to local authority budgets. This is because – unlike social care – local authorities are not obliged by law to fund bus services.

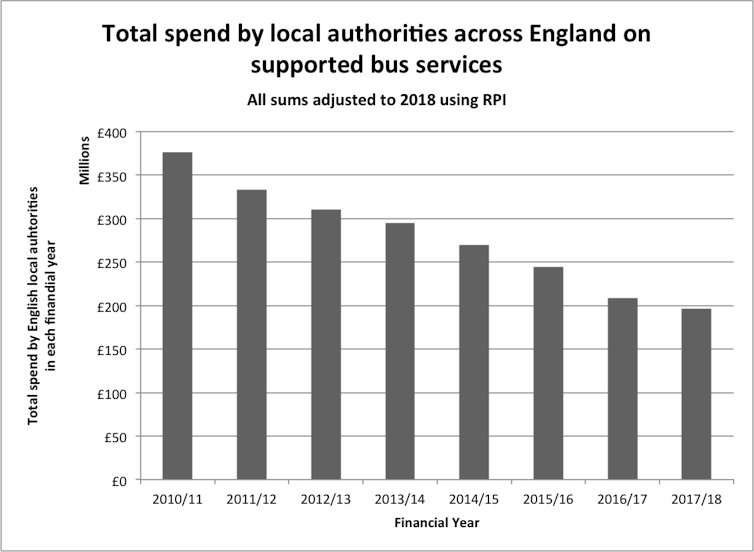

Since 2010, local authority bus funding has dropped by 46 per cent – from £374m in 2010-11, to £203m in 2017-18. A few local authorities have cut all subsidies: for example, in Oxfordshire, a 2015 FOI request from the Campaign for Better Transport revealed the agreed total budget for supported bus services in the fiscal year 2018-19 was zero. There, the community had to step in to run their own, not-for-profit service.

Local authority spend on buses in England for each financial year from 2010 to 2018. Image: Buses in Crisis Report.

Bus usage has also been in long-term decline: over the past two decades, miles travelled by bus have fallen 17 per cent. In 1990-1, bus trips accounted for 74 per cent of all public transport trips in Great Britain – today, it’s 59 per cent.

But this isn’t just a result of people switching to other forms of transport. The decline in miles travelled by bus is driven by a steep fall in travel on local government funded bus services. Travel fell 46.6 per cent over the decade to 2016-17, and 13.8 per cent between 2015-16 and 2016-17 alone. Meanwhile, over the same decade, bus miles travelled on commercially operated services have only increased by 1.8 per cemt.

Stopping the fall

Over the last 25 years, bus usage per person has increased by 52 per cent in London, while falling by 40 per cent in England’s other metropolitan areas. More than half of all bus trips in England now happen in London. London has, to some extent, managed to buck the long-term downward trend, because unlike in the rest of England, the bus market there was not deregulated.

Buses galore. Image: davidsbill/Flickr/creative commons.

London retained its ability to strategically plan and manage the routes, frequency, times of operation and fares of its buses. Its model means that profitable routes can cross-subsidise less profitable – but socially important – routes. What’s more, having control of the bus network means all the different modes of public transport can be organised to deliver better travel options to all, and a viable alternative to the car.

In 2017, the UK government passed the Bus Services Act – a tacit acknowledgement that the current deregulated bus market model is not working. The new law gives combined authorities with a directly elected mayor similar powers over bus regulation to London.

Only six regions currently qualify: Cambridgeshire & Peterborough, Greater Manchester, Liverpool City Region, Tees Valley, the West of England and West Midlands. Elsewhere, local government services are being cut further, while private companies provide limited services at high prices (over the past two decades bus fares across England have risen 45 per cent in real terms).

The Bus Services Act also bans local authorities from setting up their own bus service. Well-run municipal bus companies could save local authorities money which could blunt the severity of bus cuts – Nottingham and Reading are successful examples of this model.

![]() Regulating the bus market would clear the way for bus services to address transport inequality and poverty. Bus services help tackle social exclusion and loneliness, and allow those living outside the city centre and without a car to access employment, education and healthcare. As bus services are cut, not only do many people’s travel options shrink or vanish – so does their ability to be a part of society.

Regulating the bus market would clear the way for bus services to address transport inequality and poverty. Bus services help tackle social exclusion and loneliness, and allow those living outside the city centre and without a car to access employment, education and healthcare. As bus services are cut, not only do many people’s travel options shrink or vanish – so does their ability to be a part of society.

Nicole Badstuber, Researcher in Urban Transport Governance at the Centre for Transport Studies, UCL.

This article was originally published on The Conversation. Read the original article.