In the late 19th century, the irrepressible Mark Twain is reputed to have said in a speech:

Everybody talks about the weather but nobody does anything about it.

He’s said to have borrowed that quote from a friend, but if Twain were alive today he would no doubt have more to say on the subject. In a time when we are becoming increasingly accustomed to extremes in the climate system, the events of this year have risen above the background noise of political turmoil to dominate the global headlines.

While global leadership in dealing with climate change may be depressingly limited, I can’t help but wonder if 2018 will be the year our global tribe feels threatened enough to act.

Encouragingly, there may be a historical (and largely unknown) precedent for tackling climate change: Victoria London’s handling of the “Great Stink”, where growth had turned the River Thames into an open sewer.

Climate system extremes

This year is breaking all manner of records.

In January, the eastern USA and western Europe fell under persistent frigid Arctic conditions brought about by a weakening of the polar vortex.

Six months later, the north experienced exceptional hemispheric-wide summer warming and drought, most likely amplified by a weakening of Atlantic Ocean circulation – the latter (ironically) being expressed by unusually cool surface ocean waters.

In recent weeks, Florence, Mangkhut and Helene have become the latest household names to mark a succession of storms battering the USA, Asia and Europe this year.

Meanwhile, New South Wales is now suffering a state-wide drought, along with other regions in Australia. Early wildfires and the threat of more to come has resulted in the earliest government total fire ban on record.

As the crisis deepens, it’s worth reflecting on Victorian London’s “Great Stink” sewage problem – where things finally got so bad that authorities were forced to accept evidence, reject sceptics, and act.

A ‘deadly sewer’

In the Victorian age, London’s growth had turned the River Thames into an open sewer. Conditions were so bad they inspired many to write on the risks to public health.

‘The silent highwayman’, an 1858 cartoon from Punch magazine, commenting on the deadly levels of pollution in the River Thames. Image: Wikimedia Commons.

Charles Dickens provided a lurid description in Little Dorrit, describing the Thames as a “deadly sewer” while the scientist Michael Faraday wrote to the Times that:

if we neglect this subject, we cannot expect to do so with impunity; nor ought we to be surprised if, ere many years are over, a hot season give us sad proof of the folly of our carelessness.

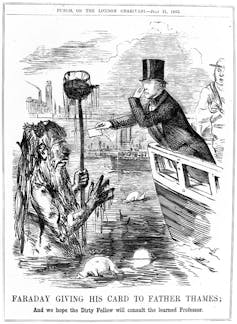

An 1855 cartoon from Punch Magazine in which Michael Faraday gives his card to ‘Father Thames’, commenting on Faraday gauging the river’s ‘degree of opacity’. Image: Wikimedia Commons.

In 1854, medic John Snow demonstrated the source of cholera in the London suburb of Soho was a local water pump. To test his ideas, officials removed the handle on the pump, and the number of cases all but disappeared.

Sewage sceptics

But there was an intransigence about meeting the threat. Ignoring scientific evidence, “sewage sceptics” held the view that poor air quality – so called “miasma”– was the cause of the frequent outbreaks of cholera and other diseases.

They convinced the government to reject the evidence, considering there to be “no reason to adopt this belief”. The scale of the sewage problem in London was considered too large to be solved, possibly encouraged by political pressure from the thriving water industry that delivered direct to those who could afford it. For several more years, this view persisted.

That was until the year of the “Great Stink”.

The ‘Great Stink’ arrives

In the summer heatwave of 1858, the Thames’ sewage turned noses across London. Conditions were so bad, teams of men were employed to shovel lime at the many sewage outlets into the capital’s river in a vain attempt to stop the smell.

Even the national legislators were not spared, with the windows of the Houses of Parliament covered in lime-soaked sack cloths. Serious thought was even given to relocating government outside London, at least until the air had cleared. The conditions created a heady stench that cut through the politically charged rhetoric of the day, and forced a rethink.

Within nine years of the “Great Stink”, the 900-kilometre London Sewage Network was constructed – an engineering marvel of the Victorian age. The politicians at the time weren’t immediately convinced the new infrastructure would help public health, but the disappearance of disease accepted as the norm for the capital convinced even the most ardent of sceptics. No one talks about miasma as a real thing anymore.

The Great Stink of 1858 overturned beliefs founded on misinformation. A challenge considered impossible, was solved.

Our generation’s ‘Great Stink’

Fast forward 160 years and the recent spate of climate headlines is on the back of an increasing trend towards greater extremes, with all the associated human, environmental, and financial costs.

In August of this year, the Actuaries Climate Index – which monitors changes in sea level rise and climate extremes for the North American insurance industry since the 1960s – reported that the five-year moving average reached a new high in 2017. This year promises to continue the trend and is no single outlier.

Will 2018 be the year when the world does something about climate change?

Will 2018 be our generation’s “Great Stink”?

![]()

Chris Turney, Professor of Earth Science and Climate Change, ARC Centre of Excellence for Australian Biodiversity and Heritage, UNSW.

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.