New York Mayor Bill de Blasio has declared that skyscrapers made of glass and steel “have no place in our city or our Earth anymore”. He argued that their energy inefficient design contributes to global warming and insisted that his administration would restrict glassy high-rise developments in the city.

Glass has always been an unlikely material for large buildings, because of how difficult it becomes to control temperature and glare indoors. In fact, the use of fully glazed exteriors only became possible with advances in air conditioning technology and access to cheap and abundant energy, which came about in the mid-20th century. And studies suggest that on average, carbon emissions from air conditioned offices are 60 per cent higher than those from offices with natural or mechanical ventilation.

As part of my research into sustainable architecture, I have examined the use of glass in buildings throughout history. Above all, one thing is clear: if architects had paid more attention to the difficulties of building with glass, the great environmental damage wrought by modern glass skyscrapers could have been avoided.

Heat and glare

The United Nations Secretariat in New York, constructed between 1947 and 1952, was the earliest example of a fully air conditioned tower with a glass curtain wall – followed shortly afterwards by Lever House on Park Avenue. Air conditioning enabled the classic glass skyscraper to become a model for high rise office developments in cities across the world – even hot places such as Dubai and Sydney.

The UN Secretariat building. Image: United Nations Photo/Flickr/creative commons.

Yet as far back as the 19th century, horticulturists in Europe intimately understood how difficult it is to keep the temperature stable inside glass structures – the massive hot houses they built to host their collections. They wanted to maintain the hot environment needed to sustain exotic plants, and devised a large repertoire of technical solutions to do so.

Early central heating systems, which made use of steam or hot water, helped to keep the indoor atmosphere hot and humid. Glass was covered with insulation overnight to keep the warmth in, or used only on the south side together with better insulated walls, to take in and hold heat from the midday sun.

The Crystal Palace

When glass structures were transformed into spaces for human habitation, the new challenge was to keep the interior sufficiently cool. Preventing overheating in glass buildings has proven enormously difficult – even in Britain’s temperate climate. The Crystal Palace in Hyde Park – a temporary pavilion built to house the Great Exhibition of the Works of Industry of All Nations in 1851 – was a case in point.

Painting of Queen Victoria opening the Crystal Palace in London, 1851. Image: Thomas Abel Prior/Wikimedia Commons.

The Crystal Palace was the first large-scale example of a glass structure designed specifically for use by people. It was designed by Joseph Paxton, chief gardener at the Duke of Devonshire’s Chatsworth Estate, drawing on his experience constructing timber-framed glasshouses.

Though recognised as a risky idea at the time, organisers decided to host the exhibition inside a giant glasshouse in the absence of a more practical alternative. Because of its modular construction and prefabricated parts, the Crystal Palace could be put together in under ten months – perfect for the organisers’ tight deadline.

To address concerns about overheating and exposing the exhibits to too much sunlight, Paxton adopted some of the few cooling methods available at the time: shading, natural ventilation and eventually removing some sections of glass altogether. Several hundred large louvres were positioned inside the wall of the building, which had to be adjusted manually by attendants several times a day.

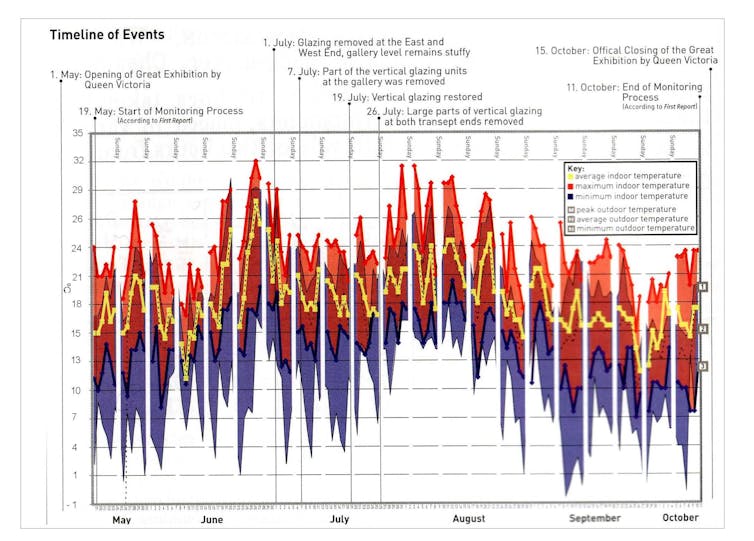

Despite these precautions, overheating became a major issue over the summer of 1851, and was the subject of frequent commentaries in the daily newspapers. An analysis of data recorded inside the Crystal Palace between May and October 1851 shows that the indoor temperature was extremely unstable. The building accentuated – rather than reduced – peak summer temperatures.

A timeline of the temperature in the Crystal Palace, May to October, 1851. Image: Henrik Schoenefeldt/author provided.

These challenges forced the organisers to temporarily remove large sections of glazing. This procedure was repeated several times before parts of the glazing were permanently replaced with canvas curtains, which could be opened and closed depending on how hot the sun was. When the Crystal Palace was re-erected as a popular leisure park on the outskirts of London, these issues persisted – despite changes to the design which were intended to improve ventilation.

Chicago glass

These difficulties did not perturb developers in Chicago from building the first generation of highly glazed office buildings during the 1880s and 1890s. Famous developments by influential architect Ludwig Mies van der Rohe, such as the Crown Hall (1950-56) or the Lakeshore Drive Apartments (1949), were also designed without air conditioning. Instead, these structures relied mainly on natural ventilation and shading to moderate indoor temperatures in summer.

In the Crown Hall, each bay of the glass wall is equipped with iron flaps, which students and staff of the IIT School of Architecture had to manually adjust to create cross-ventilation. Blinds could also be drawn to prevent glare and reduce heat gains. Yet these methods could not achieve modern standards of comfort. This building, and many others with similar features, were eventually retrofitted with air conditioning.

Chicago’s Crown Hall. Image: yusunkwon/Flickr/creative commons.

Yet it’s worth noting that early examples of glass architecture were not intended to provide airtight, climate controlled spaces. Architects had to accept that the indoor temperature would change according to the weather outside, and the people who used the buildings were careful to dress appropriately for the season. In some ways, these environments had more in common with the covered arcades and markets of the Victorian era than the glass skyscrapers of the 21st century.

Becoming climate conscious

The reality is that the obvious shortcomings of glass buildings rarely received the attention they warranted. Some early critics raised objections. Perhaps the most outspoken was Swiss architect Le Corbusier, who in the late 1940s launched an attack on the design of the UN Secretariat, arguing that its large and unprotected glass surfaces were unsuitable for the climate of New York.

But all too often, historians and architects have focused on the aesthetic qualities of glass architecture. The Crystal Palace, in particular, was portrayed as a pristine icon of an emerging architecture of glass and iron. Yet in reality, much of the glass was covered with canvas to block out intense sunlight and heat. Similarly, the smooth glass facades of Chicago’s early glass towers were broken by opened windows and blinds.

There’s an an urgent need to take a fresh look at urban architecture, with a sense of environmental realism. If de Blasio’s plea for a more climate conscious architecture is to materialise, future architects and engineers must be equipped with an intimate knowledge of materials – especially glass – no less developed than that held by 19th century gardeners.

![]()

Henrik Schoenefeldt, Senior Lecturer (US: Associate Professor) in Sustainable Architecture, University of Kent.

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.