Canada is a suburban nation. More than two-thirds of my country’s total population now live in the suburbs, meaning policy-makers must deal with the multitude of issues regarding this suburban explosion.

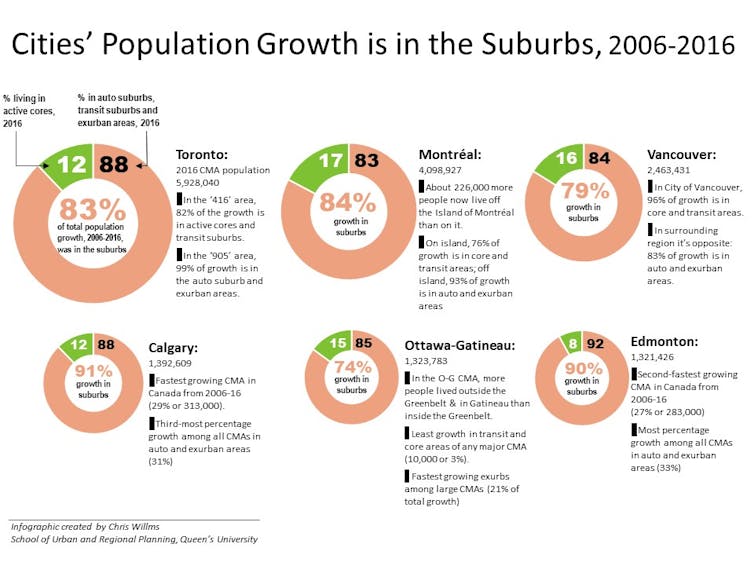

In all our largest metropolitan areas, the portion of suburban residents is higher than 80 per cent, including the Vancouver, Toronto and Montreal regions. The downtown cores of these cities may be full of new condo towers, but there is often five times as much population growth on the suburban edges of the regions.

In a 2013 article in the Journal of Architecture and Planning Research (JAPR), our research team found that 66 per cent of all Canadians lived in some form of a suburb. That figure was based on 1996 and 2006 census data.

Ten years later, that figure has risen to 67.5 per cent based on the 2016 census data released in late 2017.

The suburban sprawl in the Toronto area. Image: author provided.

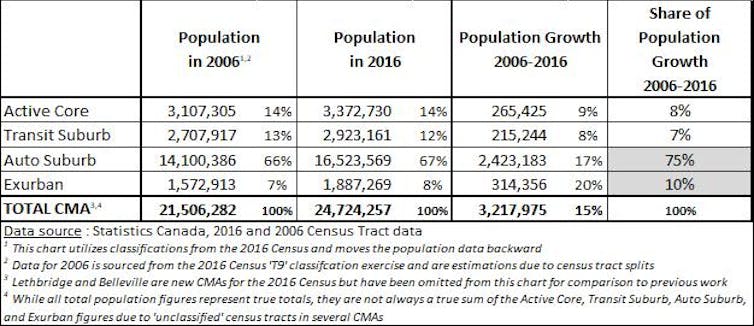

As you can see in the above Google Earth map of the Toronto area, we classified the neighbourhoods in Canada’s Census Metropolitan Areas (CMAs) into four types:

-

Exurbs: Very low-density rural areas where more than half the workers commute to the central core. They live in rural-estate subdivisions or along country roads, and comprise about eight per cent of the metropolitan population in 2016.

-

Automobile suburbs: These are the classic suburban neighbourhoods. Almost everybody commutes by car, there is little transit use and hardly anyone walks or cycles to work. They include about 67 per cent of metropolitan populations.

-

Transit suburbs: Neighbourhoods where a higher proportion of people commute by transit, comprising about 12 per cent of metropolitan populations.

-

Active cores: Downtowns and other neighbourhoods where a higher proportion of people walk or cycle to work. These neighbourhoods, which most international observers would consider “urban,” make up only 14 per cent of Canadian metropolitan populations.

Suburbs continue to sprawl

In the new census data, our research team found that within Canada’s metropolitan areas, 86 per cent of the population lived in transit suburbs, auto suburbs or exurban areas, while only 14 per cent, as mentioned above, lived in active core neighbourhoods.

The active cores and transit suburbs grew by nine per cent and eight per cent, respectively, below the national average population growth of 15 per cent. The auto suburbs and the exurban areas, on the other hand, grew by 17 per cent and 20 per cent respectively, exceeding the national average.

The net effect of this trend is that 85 per cent of the Census Metropolitan Area (CMA) population growth from 2006–16 was in auto suburbs and exurbs. Only 15 per cent of population growth was in more sustainable active cores and transit suburbs.

The 2006–16 findings show that the population of Canada’s auto-dependent communities is growing much faster than the national growth rate, which has significant policy implications when it comes to public health, transportation, education planning, electoral issues and community design.

Source: statistics Canada Census Data, 2006-16.

The national pattern is similar regarding construction of new residential units, though not as extreme. That’s because new housing units in the active cores have about 40 per cent fewer occupants than those in auto suburbs, according to 2016 data.

Even if dwelling units are a growth measure, 78 per cent of new dwelling unit growth from 2006-2016 occurred in the less sustainable auto suburbs and exurbs.

Many people over-estimate crowding and traffic in highly visible downtown cores and underestimate the vast growth happening in the suburban edges of our metropolitan regions.

The population in low-density auto suburbs and exurbs is still growing five times faster than inner cities and transit suburbs across Canada.

Despite their inner-city condo booms, even the Toronto and Vancouver metropolitan areas saw 3.4 and 2.4 times as much population growth in auto suburbs and exurbs compared to active cores and transit suburbs.

Canada is, in fact, a suburban nation, and its population became more suburban from 2006–16, despite the planning policies of most metropolitan areas.

A graph showing population growth patterns in major Canadian metropolitan areas. Image: Author provided.

Preliminary 2016 census analyses in some CMAs show that the past decade of municipal intensification policies is finally having an effect on the location of dwelling units, but the large majority of population growth still continues to occur in automobile suburbs and exurbs.

This means policy-makers must:

- Monitor the edges of metropolitan areas more closely than the centre;

- Set growth and intensification targets using both population and housing units;

- Calibrate infrastructure programs to shape suburban population growth;

- Increase bus rapid transit and light rail transit, rather than subways, subways, subways.

-

Even if urban development trends were to become significantly more intense, the current suburban neighbourhoods will comprise the bulk of the nation’s housing stock well into the 21st-century. That means Canada appears destined to remain a suburban nation in the decades ahead. It’s time for governments and policy-makers to grapple with the myriad implications.

David L.A. Gordon, Professor, School of Urban and Regional Planning; Department of Geography and Planning, Queen’s University, Ontario.

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.