Australia has not had a national urban policy since the Rudd government. A troika of Liberal PMs followed. Tony Abbott wasn’t interested. Malcolm Turnbull didn’t quite live up to the hype but delivered cross-governmental City Deals and the Smart Cities and Suburbs Program. Scott Morrison at best presided over a business-as-usual approach lacking any resolve, urgency or innovation.

Will this Labour government do any better? Australian cities and regions were not front and centre in the 2022 federal election campaign. But there were signs a Labour government would reinstate a concern for urban policy issues.

The federal budget confirmed the government’s focus on urban policy. It set aside funding for a “national approach for sustainable urban development” and a “cities program”. Last week the government appointed the expert members of the Urban Policy Forum announced in the budget.

These are vehicles for delivering a promised National Urban Policy. The government says this policy “will bring together a vision for sustainable growth in our cities”.

Why focus on cities?

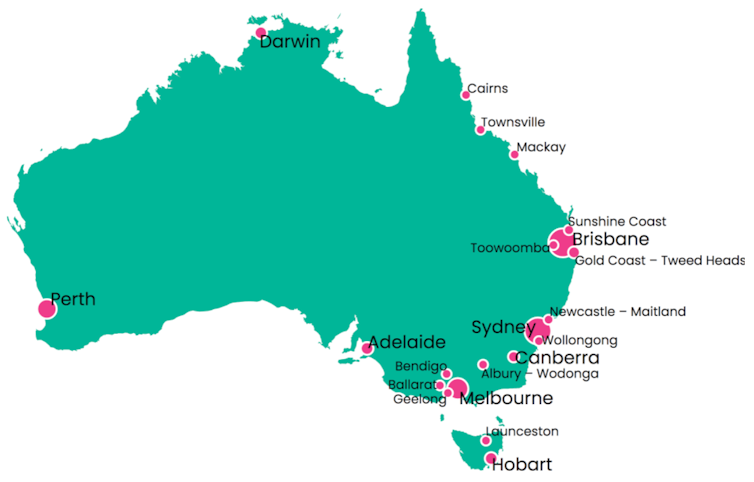

Two in three Australians live in a capital city. Our 21 largest cities are home to 80% of the population.

Cities account for 80% of economic activity in Australia. As globally connected hubs, they are crucial sites for community, commerce, infrastructure, biodiversity, governance and democratic processes. Our cities are central to meeting the challenges of a changing climate.

Prime Minister Anthony Albanese has skin in the game. He was the minister for infrastructure and transport in the Gillard government. He oversaw the first truly national urban policy, Our Cities, Our Future, in 2011.

In 2021, Albanese declared that “cities policy has been one of the abiding passions of my time in public life”. He foreshadowed a new national policy framework.

The budget papers specifically refer to the National Cabinet agreement on April 28 on national priorities. Among these is “Better Planning for Stronger Growth reforms to support a national approach to the growth of cities, towns, and suburbs”.

The budget commits nearly A$400 million over four years in new grants and investments in “Thriving Suburbs” and “Urban Precincts and Partnerships”. Some $11 million goes to a Cities and Suburbs Unit to deliver a National Urban Policy. The policy is required to “address urgent challenges facing our major cities – from equitable access to jobs, homes and services, to climate impacts and decarbonisation”.

An overdue development

Urban development has been “undervalued in national discussion” globally, not only in Australia. But in recent years various bodies, inquiries and forums have pushed for a new-look national urban policy.

The Planning Institute of Australia has long called for a coherent governance framework for spatial plans, infrastructure, growth management and urban renewal. Without a national cities plan, a 2018 report by the institute said, “all jurisdictions will be disadvantaged when making resource allocation decisions and planning for basic enabling infrastructure”.

In the same year, a federal parliamentary inquiry into the Australian government’s role in city development called for “a national plan of settlement, providing a national vision for our cities and regions across the next 50 years”.

In 2019, Future Earth Australia, based at the Australian Academy of Sciences, advanced a ten-year national strategy for sustainable cities and regions. This strategy is aligned with the Australian achievement of the UN Sustainable Development Goals.

New ideas for Australian cities and regions

We must take seriously the economic, social and environmental impacts of long-term population growth and development. To become a more equitable and sustainable country, action on the uneven experiences of Australian cities and regions must be a government priority.

In 2021, an Australian Academy of Social Sciences workshop on Australian Urban Policy: Achievements, Failures, Challenges was undertaken jointly at the City Futures Research Centre, UNSW, and Centre for Urban Research, RMIT University. More than 50 researchers and practitioners explored the many issues competing for urban policy attention at the national level.

Key areas included water, climate change, Indigeneity, transport, migration, population settlement and new cities. Urban green space, biodiversity, digital technologies, economic productivity, social inclusion and affordable housing supply were also identified as issues that cut across national policy agendas.

Constitutional constraints mean states must play a leading role in national urban policy. Fortunately, these constraints don’t rule out inter-governmental partnerships. There are many, often poorly integrated policies, programs and initiatives across all levels of government.

There was consensus at the workshop on the need to transcend the political ideology and expediency that have led to fragmented urban policies. A different kind of national politics focused on sustainability, resilience and regeneration is required.

The “secret” to sustainability lies in an integrated national framework of policies and strategies for city-regions. All three tiers of government need to buy into it.

National urban policy redux

There is a “back to the future” quality in some of the Albanese moves. They re-invent Rudd-Gillard initiatives, and Turnbull’s City Deals remain. Action on affordable housing supply and urban inequalities has been less forceful to date.

Sitting alongside what seem like far-reaching environmental actions, including a new Net Zero Authority, the revival of urban policy at the national level is welcome. So too would be the discussion, consultation and research required to secure a resilient and sustainable future.

A national urban policy offers opportunities for cities, towns and regions.

It’s also essential if Australia is to meet its national and international obligations, notably the UN’s 2030 Agenda for Sustainable Development.

Australian Urban Policy: Prospects and Pathways is a report on the UNSW-RMIT workshop edited by the authors and with over 30 contributors. It will be published by ANU Press in late 2023.

This article by Robert Freestone, professor of planning, School of Built Environment, UNSW Sydney; Bill Randolph, professor, City Futures Research Centre, Faculty of the Built Environment, UNSW Sydney, and Wendy Steele, interim director, Urban Futures Enabling Impact Platform, and professor in Sustainability and Urban Policy, Centre for Urban Research, RMIT University, is republished from The Conversation.