The UK government has spent more than a billion pounds on surveillance technology in the past five years, including a contract worth up to £1bn on drones to spot migrants crossing the English Channel. Critics warn that using drone surveillance to deter illegal human trafficking “makes no sense from an economic perspective”.

The Home Office has spent more than £1bn on surveillance technologies including drones and “near real-time” situational awareness platforms in the last five years, according to an analysis of procurement data by Tech Monitor.

The largest contract was won by Tekever, a Portuguese defence technology company that specialises in unmanned aircraft systems. In 2019, the company was awarded a three-year contract worth up to £1bn by the Home Office “to enhance maritime awareness”. This contract is set to end on 30 September this year.

The contract does not specify precisely how the technology is used, but at last year's Defence and Security Equipment International conference in London, Tekever’s UK managing director Paul Webb revealed that the Home Office uses its products for migrant surveillance.

“Every day, dozens of asylum seekers and refugees set off on the dangerous journey across the English Channel to reach British soil, but small boats and treacherous conditions mean many lives are in danger along the way,” he said. “We are proud to be a partner of UK authorities in fighting this kind of illegal human traffic. Drones can identify humans in distress in a much faster way and help rescue teams.”

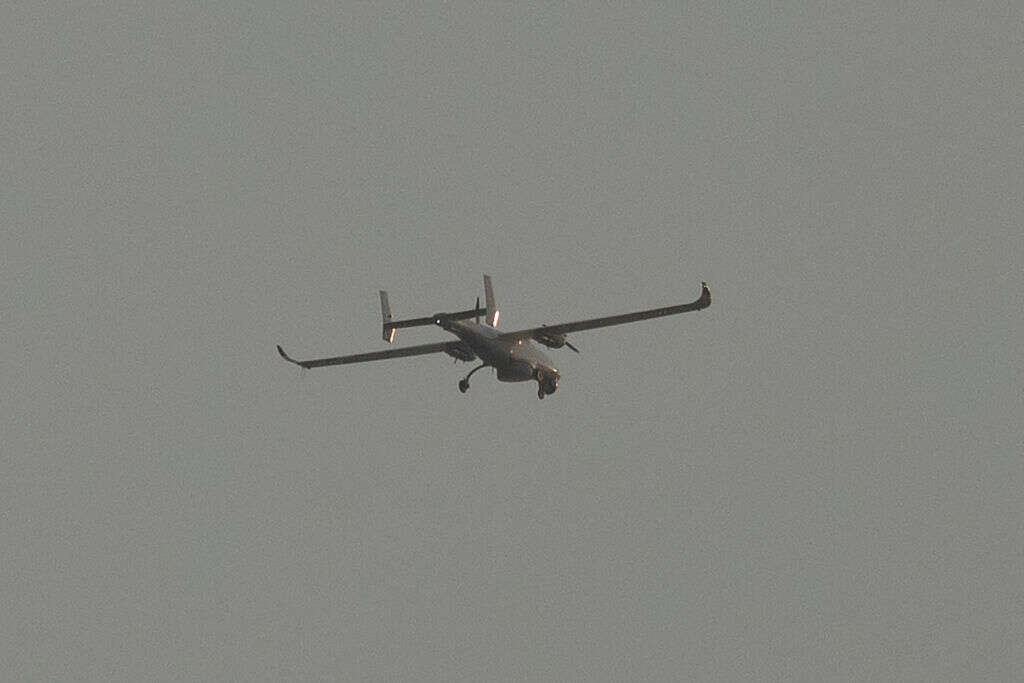

Tekever's products include the AR5 drone, dubbed “Europe’s first UAS-based maritime surveillance system”, which is equipped with sophisticated imaging capabilities and “advanced AI analytics”, the company says. Applications include civilian uses such as monitoring critical infrastructure and the environment, as well as maritime and “anti-terrorist” surveillance missions.

Aside from the Home Office, the company's clients include the European Space Agency and the European Maritime Safety Agency. It has also reportedly provided its products to armies and navies in Colombia, Nigeria, Senegal, and Indonesia. Tekever did not respond to a request for comment.

UK using drones to spot migrants 'makes no sense'

The number of people who crossed the English Channel in small boats tripled in 2021, reaching 28,431. The Union Borders, Immigration and Customs expects the figure to reach 60,000 this year, in part due to Russia's invasion of Ukraine.

But experts question how useful drones are in preventing illegal migration and human trafficking. While it may be effective in detecting small boats, maritime surveillance does nothing to address the source of the issue, says Rob Anderson, principal analyst for central government at GlobalData.

“Just having surveillance drones is not going to stop small boats crossing the Channel, so it’s a technological answer to a different problem,” he says. “In terms of value for money, I’m not convinced.”

Dr Leonie Ansems de Vries, chair of the Migration Research Group at King’s College London agrees. “These are staggering amounts of money being spent on drones but at the same time, it’s also not a surprise if you look at the longer history of migration management in the UK,” she says. “The overall vision and narrative of the Home Office in recent years has been focused on keeping people out, rather than providing safe and legal routes which would be a lot cheaper and safer.”

“So there’s a desire to continue investing in surveillance technologies and other possible policies like offshore detention centres for example, even if it makes no sense from an economic perspective,” she adds.

The Home Office has also used Tekever's technology in criminal prosecutions against smugglers and human traffickers, according to a Sky News report. A 36-year-old Iraqi national was jailed for assisting unlawful immigration based on footage gathered from these drones.

But using surveillance to detect human traffickers can be counterproductive, says de Vries, citing examples from the Mediterranean. “These people won’t get onto the boats, instead they’ll designate another person to drive a boat and that person is often someone who’s fleeing themselves,” she says.

“This is really important because you cannot identify who’s leading the smuggling operation by looking through the lens of a drone,” de Vries adds. “A drone can see something but it cannot understand the wider context and the relationships of power between smugglers and migrants and so on.”

Home Office agencies are reportedly planning to spend an additional £385m on drones, patrol boats, and biometric solutions by the end of 2022 to target people attempting to cross the English Channel, according to analysis by Corporate Watch.

De Vries suggests this money would be better spent elsewhere as the country faces record levels of inflation and a cost of living crisis. “These technologies don't actually do anything other than what I call the politics of exhaustion, or making people’s lives really difficult and deterring them by any means necessary,” she says.

“What we’re seeing are technological solutions to problems that are essentially political and of a humanitarian nature.”

This article originally appeared on Tech Monitor.