Annie Brissette has had one hell of a time finding a new apartment in Montreal.

Every day over the past five weeks, she’s scoured online classifieds sites and Facebook groups for apartment rentals, looking for the elusive one-bedroom under $1,000 that’s ready to receive her and all her stuff. Time and time again, she saw apartments that were advertised as fully furnished – an anomaly in Montreal, where apartments often don’t even come with their own appliances.

“I think there’s a huge proliferation of Airbnb apartments on the market, because it’s unbelievable the number of fully furnished apartments that aren’t available empty,” Brissette says. Many of the apartments she’s seeing are furnished down to the decor. “You feel like you’re at someone else’s house, but you know you’re really at an Airbnb.”

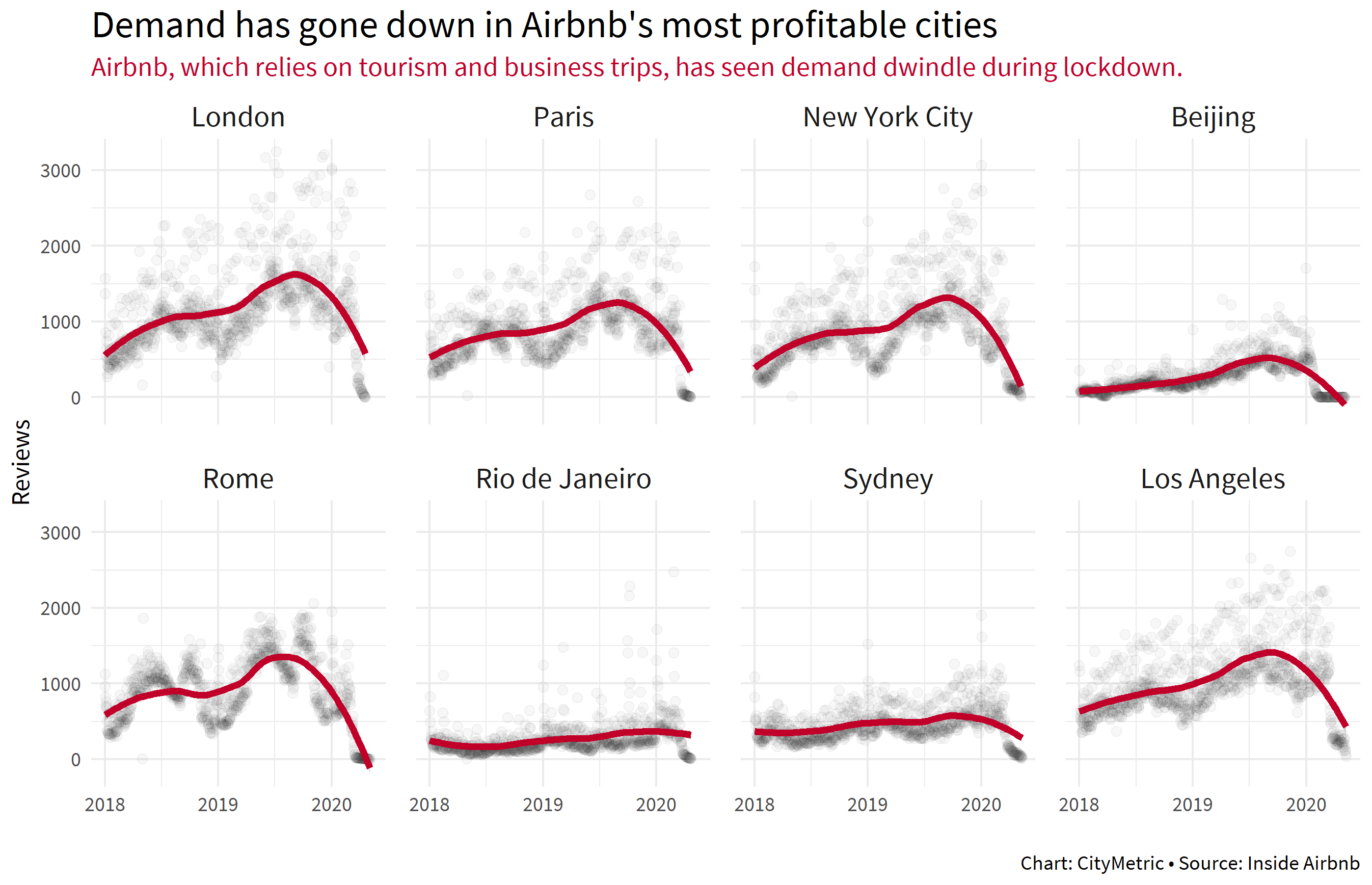

The province of Quebec banned Airbnb and other short-term rental services during the Covid-19 state-of-emergency. That, plus the collapse of summer tourism, is pushing hosts onto other platforms. Some are illegally operating short-term rentals, but many are flipping their homes back onto the long-term market while cutting Airbnb out as the middle man.

This trend is growing legs across North America as the short-term rental market bottoms out during the pandemic. Despite temporary bans on Airbnb-type rentals in Ontario, Florida, Pennsylvania, Georgia, Delaware, Maine and Vermont, potential renters have been able to find listings for suspiciously clean, well-appointed, fully furnished apartments with flexible leases and high rents via non-Airbnb rental sites in cities like Toronto, Philadelphia, Atlanta and Vermont’s ski towns.

“We are seeing a lot of inventory,” says John Pasalis, a Toronto housing market analyst and president of Realosophy Realty. “[Since the start of the pandemic] a lot of sellers didn’t put their units on the market, but a lot of renters did. We saw strong listing growth, particularly in the downtown core.” The oversupply there, he continues, has led to a 5% price drop on downtown rentals.

But before anyone celebrates the drop, consider the pre-pandemic rental affordability crisis. The influx of moderate- to high-cost Airbnb units on the long-term rental market may be giving top-tier renters more options, but it’s having negative effects on lower-income earners.

Researchers have shown that the presence of Airbnb-type housing has increased overall asking prices in some cities, while reducing the amount of affordable housing available. It also makes competition fiercer for lower-cost housing, to the extent that some people may feel compelled to overbid on rent to secure housing. If the units returning to the long-term market cost more than what renters can reasonably pay, but they’re the only options available, more people may find themselves financially overextended.

“I mean, a 5% decline… You know, when one-bedroom condos were renting for over 2,000 bucks a month, that’s $100. You know what I mean? Sure, that’s good, but $1,900 is still very expensive,” Pasalis says.

The bigger picture

For the past couple of decades, affordable rental housing in the U.S. had been in slow decline. Then, sometime around 2012, it fell off a cliff.

Alex Hermann, research analyst at Harvard University’s Joint Center for Housing Studies, measures the fall of low-cost housing in the U.S. “From 2014 to 2018, the number of units renting for under $600 declined by about a half a million units per year on average. That’s about 2.7 million units in total,” he says. At the same time, units going for more than $1,000 a month increased by just under 5 million over that same period.

The percentages are even starker. In 2000, housing under $600 represented 36% of the rental supply. It was 30% in 2014, and 23% in 2018. Hermann says this is creating a chasm between supply and demand for low-rent homes, which is widening at a pace greater than the wages of low-income Americans.

The timing of the accelerated decline is curious. It happened on the heels of the 2008 crash and the Great Recession, which cast 10 million homeowners into foreclosure. Shareholder-backed institutional investors bought up a large portion of those foreclosed homes, which professionalised the landlord class and made it increasingly profit-driven. Airbnb’s first massive wave of growth happening between 2011 and 2014 was not uncoincidental. As much as short-term rentals enabled at-risk homeowners to afford their homes, they also incentivised speculators to hoard and flip housing.

Preventing a deepening crisis post-pandemic

Today, as Covid-19 triggers the highest levels of unemployment in 100 years and millions of American tenants are at risk of defaulting on their rent, the state of rental housing is approaching another dangerous precipice.

Presently, mom-and-pop landlords own more than half of the rental stock under $750 per month. If their tenants default, those building owners may not be able to stay solvent. That makes them susceptible to speculative buyers, says Maya Brennan, senior policy program manager at The Urban Institute. “We’re in the very early stage, really, of being able to prevent that problem of rental units going offline or being acquired by investors whose only motive is to maximise profits, and not maintain a healthy housing market in a region,” she says.

The best emergency measure to prevent that from happening is making sure everyone can pay their rent, especially if they owe a small landlord. The next step, Brennan says, is to create strong programs that give existing tenants, or the public sector, the right of first opportunity to buy insolvent properties, in order to maintain affordable housing. If neither of these things happens, the crisis will get worse, she says. “And that’s not something we can bear.”

As for Airbnb hosts’ flip to the long-term rental market, it’s not yet clear whether it will have any kind of positive impact on affordable housing. It could create more supply and drive down prices. Cities and states could use the pandemic as a time to introduce tighter controls, which could redivert housing back to long-term tenants. Or we could just relive the past 10 years all over again.

Back in Montreal, after five weeks of searching, Brissette has just found a one-bedroom in the city’s Little Italy area. Rent is steep at $1,600 a month, which is double what anyone would have paid just a few years ago.

“I’m lucky to have found it – and lucky to be able to afford it,” she says.

Tracey Lindeman is a freelance writer based in Ottawa.